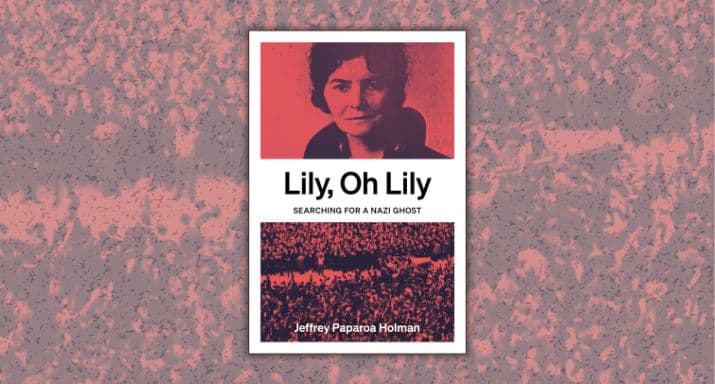

Extract: Lily, Oh, Lily: Searching for a Nazi Ghost, by Jeffrey Holman

What if the dead - our dead - never feel to us that they have gone? If family stories, fragments of their lives, continue to nag and haunt us? Lily Hasenburg was just such a figure in Holman's growing years. She was whispered into his ear by grandmother Eunice - in memorable stories of her older sister, who married and moved to Germany at the turn of the 20th century, and was later caught up in the Nazi web spun by Adolf Hitler. Unable to shake loose this story, Holman pursued her to Berlin, Hamburg and Dresden. Here, we have an account of his pilgrimage; the kind of family history we might bury, and forget - to our loss.

Extracted from Lily, Oh, Lily by Jeffrey Holman. RRP $36.99. Published by Canterbury University Press. Published Oct 2024.

My great-aunt Lily had come back from Hamburg some years before this, for her niece Lillian’s funeral in August 1934. Lillian, my mother’s older sister, had been suffering from what was then an incurable condition, Hodgkin’s lymphoma. She was nursed at home by my grandmother until the inevitable end. In her diary, on Monday the 13th of that month Nanny wrote, ‘Lillian died, at 10.45 in my arms. My heart broke.’ That same day, my mother was freed from the Bluecoat School nearby: ‘Mr Wilson sent Polly home’. The next entry is Friday the 17th: ‘We buried Lillian, how beautiful she was, just asleep, & free from pain & trouble’. Nanny hardly had time to compose herself, in heartbreak. On Tuesday the 21st of August, we read, ‘Mother had a stroke’. First her daughter; now her mother. By Saturday, she too is gone: ‘Mother died at 9 a.m.’

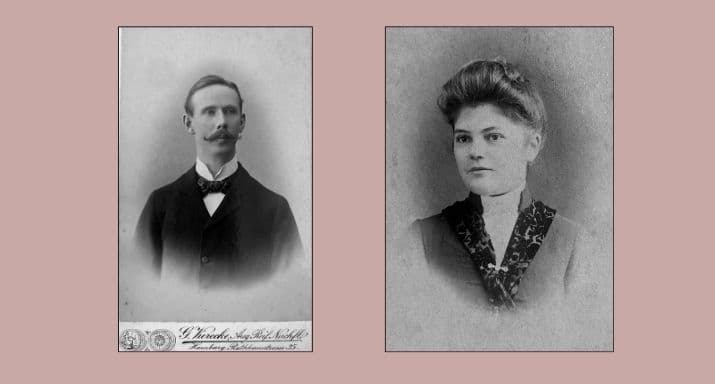

Carl Hasenburg and Lily Hasenburg Bywater, from family albums supplied by the author

Nanny was left alone to hold things together, to swallow her multiple griefs and manage these final farewells of her beloved family. The following day, on Wednesday, ‘We buried Mother’; on Thursday, when it is all over, ‘Lily came 5.30 am’. Too late. Writing this, having once again carefully taken down these bare, heartbroken details from the diary she left behind – that came to me when my own mother died in 2005 – it does not surprise me to read that a month later, Tuesday the 18th of September, she was ‘taken ill with chill and nerves’. Nanny had suffered a perfectly understandable nervous breakdown.

What has this to do with Germany, then, and Hitler? Another death had preceded these departures: on the 2nd of August 1934, German President Paul von Hindenburg had died, and Adolf Hitler, already elected as chancellor and virtual dictator, announced that his office and that of president would be combined. In between Lillian’s death and her grandmother’s, Germans could vote in a plebiscite on the merging of the two offices and Hitler’s new role as Führer. Some 95.7 percent of the population voted; 89.93 percent in favour of Hitler. Hindenburg’s exit – the last link with Germany’s pre-war imperial past – left no restraints at all now on Hitler: Führer and dictator, unhindered.

This seems to me the most likely moment at which my great-aunt Lily made the statement my grandmother never forgot, nor forgave, remembered perhaps in bitter hindsight in the light of what was to come, five years hence. ‘Hitler,’ Lily told her grieving sister, ‘is a great man, Eunice. He is doing wonderful things for the German people.’ I can still sense the bitterness and the anger in her retelling of this statement. Had events not unfolded as they did, had the oncoming war never happened, such a remark would have been forgotten; yet here Eunice was, thirty years later, pouring her anger and grief into her grandson.

That was August 1934; yet twenty years earlier, at the outbreak of the Great War; my great-aunt Lily, as the English wife of a German citizen, had found herself and their two children on enemy territory. How did she get there?

To answer this, we must go back to the late 1890s, a time when her father – my great-grandfather – had entered another of his manifestations: he was now a rubber-stamp maker, in Liverpool. Peter Daniel Bywater was a Welshman, born in rural Caersws in 1843. According to my grandmother, he had fled the area after assaulting a school master. Like thousands of other young Welshmen from all over the reach of the English throne, he had taken ship for America. His many adventures there, she said, included riding the short-lived Pony Express, meeting William Cody, and later fighting in the American Civil War. This latter claim I am able to verify from passenger records on one of his many later Atlantic crossings. His Civil War service was noted on the RMS Ivernia’s passenger manifest in 1909 as being that of a true US citizen. ‘Born USA’, it reads – which we know was not the case. Was he claiming this, or was his grant of citizenship due to his wartime service? Whatever the truth, he could now travel as an American, and his children would certainly trade on this later in life.

Cody – as Buffalo Bill – certainly did come to Liverpool in 1891, with his Wild West Show. From my Nanny’s account, she was thirteen at the time when her father took her – along with Lily and their brothers Ulysses and Hector – to the street parade of the performers, freshly landed from America. Before his children’s very eyes, their father, who had claimed he knew Cody well, strode out from the crowd as Cody rode by and called out, ‘William!’ Buffalo Bill called back, ‘Peter!’ Cody then leapt off his charger and, before the dumbstruck children, the two men embraced like the long-lost friends they were. From the eighty-year-old time zone where Nanny lived, these stories sounded authentic, invading our porous, pubescent worlds where anything could still be possible. Now, I have no doubt this is true. P.D. Bywater was quite a man, and by the time we meet him, later in life making his rubber stamps, he had more than filled his cup of life to the brim.

It is as a rubber-stamp maker that our family’s German connection begins. Needing supplies for his growing business, my great-grandfather made contact with Carl Hasenburg, a rubber trader from Hamburg. The city was at the time a centre for the growing trade of this increasingly important resource: in military terms alone, rubber was now a strategic material for the prosecution of colonial and imperial ambitions – and wars. Motor vehicles alone used rubber tyres in huge quantities, as well as engineering changes in seals and drive systems. Carl Hasenburg did indeed begin supplying P.D. Bywater with the necessary rubber.

In untangling family history, there are times we might wish we had never stumbled on certain things, while drawing blanks on other matters that we may have thought were important.

About the author

Jeffrey Paparoa Holman is an acclaimed poet, historian and memoirist. His poetry has been shortlisted for the New Zealand Book Awards; his family memoir The Lost Pilot (Penguin, 2013) was warmly received in Aotearoa and overseas. Best of Both Worlds: The story of Elsdon Best and Tutakangahau (Penguin, 2010) was short-listed for the Ernest Scott Prize (History) in Australia. Since retirement from his role as senior adjunct fellow at the University of Canterbury, he has taught creative writing in both primary and high school programmes.