Extract: Power to Win, by Lyndy McIntyre

In this extract, the preface to Power to Win, Lyndy McIntyre introduces us to the Living Wage movement.

Ko Te Awakairangi tōku awa

Beside Te Awakairangi Hutt River, and just north of Pōmare, is the entrance to Stokes Valley, where I spent the first 13 years of my life. My friends at Stokes Valley School came from a wide range of families. In Kamahi Street, by the bus barns and the top shops, lived a ship’s captain, a dentist and a dustman. After school, we played at each other’s homes. Some were flasher than others, but they were all comfy, warm and dry. We shared meals together. We went to the flicks at the Bug House on Saturday afternoon down on Main Road, past the fire station and the butcher’s shop. To my young eyes, it looked as if everyone had enough; as if all families did things together. In my Stokes Valley world, where the mums stayed at home and every dad had a job, it seemed as if everyone could afford the fare, the sports gear or the movie ticket.

How different my old home is now. The Hutt Valley is a place of huge disparity, with extreme wealth and poverty. I took a drive up Stokes Valley recently. The streets are worn out and beaten up, and the valley is home to the families of low-paid workers who must weigh up what the family can do without.

Lemo Lemo lives with his wife on Stokes Valley Road, not far from Kamahi Street. He’s 62 and works two jobs to pay the bills and to support his extended family. Although their flat is small and basic and doesn’t feel the sun until late in the day, the rent is $400 a week. Lemo is a long way from his village, Safotu, on the Sāmoan island of Savai'i. Stokes Valley is home now, but with a full-time labouring job on road works plus a cleaning job for four hours, five nights a week, Lemo scarcely sees it. He rises at 5am and travels to Wellington in company transport for his labouring job. After being dropped home at the end of the day, he drives himself back to the city to clean at Victoria University before arriving home again after 11.30pm. Life is ‘work, home, work, home, work’. When he’s 65, he says, he’ll ‘carry on’.

The fifties and sixties were a time of plentiful housing, near-zero unemployment and wages families could live on. In the Hutt Valley, car factories offered a bonus to staff who could get others to work with them for more than three months. Staff were bused in from other areas. Jobs were plentiful, and even the lowest-paid positions attracted allowances and penal rates for evening and weekend work.

Somewhere in the past 50 years, between my life in the valley and today, Aotearoa went from being one of the most equal countries in the OECD to one with pronounced inequality of incomes and wealth. We see the results all around us.

Every evening, thousands of cleaners like Lemo Lemo leave their homes to clean through the night in the city. In Wellington, they come from outlying suburbs like Stokes Valley, Cannons Creek and Naenae. This invisible army travels by public transport when they can and by car if they can’t; if that car breaks down on the way to work and there is no credit on their cellphone to ring the boss, they risk getting the sack.

They leave their families behind in cold substandard rentals with empty cupboards and piles of unpaid bills. Those who are parents may have crossed paths briefly with their partner to hand over the care of their children, or the kids are home alone. Most, but not all, of these cleaners are women. They are very likely to be Māori, Pacific or a new migrant.

In 1990 I started working as an organiser for the Northern Hotel and Hospital Workers Union, which, through amalgamations with other unions, became first the Service Workers Union of Aotearoa, then the Service and Food Workers Union, and later the union E tū. Our union’s membership included three of the lowest-paid jobs in Aotearoa: cleaners, security guards and caregivers. In 2011 I returned to the Service and Food Workers Union as media officer and magazine editor, and met hundreds of low-paid workers with the same stories. I went into their homes and saw the reality of the working poor: families huddled under rugs in houses without heating, their couches threadbare, their fridges empty.

Union members had already been campaigning for years to change this. One of these, cleaner and union delegate Jaine Ikurere, after some 20 years of cleaning the prime minister’s office was still working two jobs and putting in 50 hours a week to make ends meet. In October 2011 she and other parliamentary cleaners hosted a lunch for politicians, at which they told their stories. On the table in front of them they placed a meagre pile of groceries, the typical contents of a weekly shopping basket for a cleaner on the minimum wage. For Jaine, a pay rise would allow her to buy food, heat her home and buy birthday presents for her grandchildren.

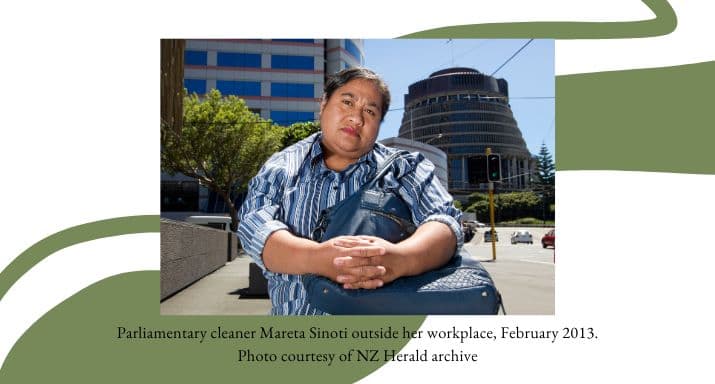

In May 2013 I visited cleaner Mareta Sinoti’s house in Cannons Creek to prepare for an interview for the television current affairs programme, Campbell Live. The film crew wanted to follow Mareta and other cleaners as they worked through the night at Parliament. Mareta had two teenage sons, and her husband was unwell and unable to work. Mareta worked two jobs to support the family. Before her shift at Parliament, she cleaned the High Court in Molesworth Street, across the road from the Beehive, then, at midnight, after an hour’s unpaid break, she joined other cleaners at the seat of power. They worked for the minimum wage with no extra pay to acknowledge the inhospitable hours.

In the cleaners’ homes I heard story after story of working long hours to feed the family. At every visit I asked our members, ‘What is your dream?’ The answer was always the same: a better life for their children. In Mareta’s house there was little furniture, but the walls were covered in family photos along with certificates and other evidence that the children were doing all right at school. Mareta wanted to buy rugby boots and other sports gear and pay for school trips: ‘All the things we need to give our kids an equal chance.’ Long hours and poverty-level income could not realise this dream; workers routinely missed parent-teacher appointments, and their children missed out on class trips and lunches.

Nearly five years later these cleaners finally won the pay rise they had campaigned for. On 18 December 2017, around 20 leaders from faith groups, community organisations and unions gathered at Parliament to hear the Speaker of the House announce that parliamentary cleaners had been awarded the living wage – a pay rise of around 30 percent.

The outcome was the legacy of the hundreds of cleaners who had campaigned tirelessly. It came too late for Jaine Ikurere, and Mareta Sinoti, her children now grown, was by this time cleaning the National Library across the road from Parliament, but it was their legacy too. For the cleaners who came after them, the increase was transformative. At Parliament in December 2017, E tū member and cleaner Eseta Ailaoa told workers and supporters that at last she’d be able to save money to take her children on a holiday.

The community leaders who gathered at Parliament in December 2017 were celebrating a victory for Living Wage Movement Aotearoa NZ. This is the story of that movement.

Extracted from Power to Win: The Living Wage Movement in Aotearoa New Zealand by Lyndy McIntyre, published by Otago University Press. RRP $45. https://www.otago.ac.nz/press/books/power-to-win