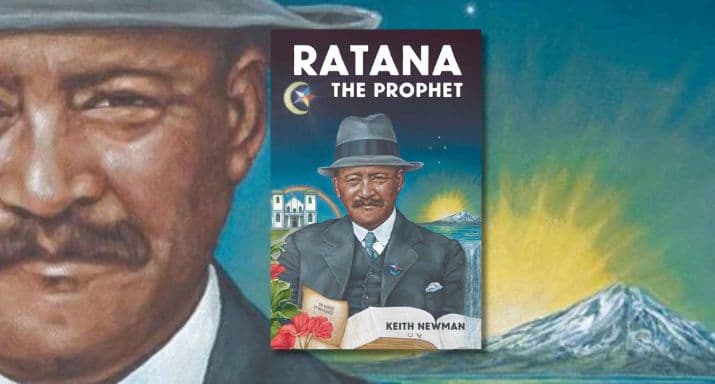

Extract — Ratana the Prophet, by Keith Newman

The Ratana movement gains national coverage every February as politicians make the pilgrimage to its headquarters near Whanganui, yet the history and workings of the religion are less widely recognised. In this new edition of his standard biography, Keith Newman reveals the life and times of Tahupotiki Wiremu Ratana and the movement he founded in 1918, tracing its activities and influence up to the present-day community of some 50,000 followers. Extensively illustrated colour and black & white photographs.

Read on for an excerpt from the updated 2024 edition.

Excerpt from Ratana the Prophet, Keith Newman, Oratia Books, May 2024, pp 77–80

Taking it to the top

Ratana’s efforts to record the stories of how various tribes had lost their land had resulted in 34,000 signatures – an incredible number, considering the Māori population at the time was only around 57,000.

Despite the overwhelming desire of the people to have the Treaty of Waitangi honoured, the government, including its Māori members, ignored the petition. The Native Department, responsible for listening to the voice of Māoridom, retained its hostile attitude towards Ratana. A more direct approach was needed. Ratana would take the petition and copies of the Mäori version of the treaty, along with reams of supporting documentation, to England. He would present it to King George, asking him to intervene and put things right.

The Ratana movement was growing in size and complexity, and it was agreed that a new organisational structure was necessary to co-ordinate the efforts of various committees around the country, share the workload and maintain focus. The Kotahitanga Council was established at Ratana Pä before the impending first world tour in April 1924.

The council would take responsibility for farming the land at Ratana, investigate land claims and take care of health, education and fundraising. Also established were a number of sports, cultural, educational and musical groups and committees. Ratana was attempting to shift the focus from himself and give more responsibility to those who would act wisely on behalf of the growing Ratana community and, ultimately, all Māoridom.

However, one of the society’s first decisions was possibly its worst. It determined to create an investment society known as the Bank of the Kotahitanga, or the Savings Bank of the United Mäori Welfare League of the Northern, Southern and Chatham Islands. It claimed it could raise £37 million for the ‘advancement and good of the people’. … Ratana was surprised that things had so quickly become focused on finance. He warned the council that it did not fully understand its own ‘power and authority or jurisdiction’ or the full impact of what it was proposing. …

There was great excitement at the Christmas gathering and much work to tie up the loose ends for the ambitious plan to visit ‘the United Kingdom, France, the United States of America and Japan’. The ‘world tour’ would attend the Empire Exhibition in London and ultimately present the Treaty of Waitangi petition, including signatures from two-thirds of Mäori to King George V.

In the touring party would be Ratana’s wife Te Whaea and children Tokouru, Matiu, Arepa, Omeka, Piki and Maata, along with two performing troupes of twelve young people. A small administrative team would join them, along with a group of elders, including the main organiser and spokesman Pita Moko, the prime minister of the Kïngitanga Mäori Parliament Tupu Taingakawa Te Waharoa, Reweti Te Whena, and Ratana’s friend and advisor Pepene Eketone, who would act as Mäori interpreter.

The first issue of the Ratana newspaper, Te Whetu Marama o Te Kotahitanga appeared on 15 March 1924 with enthusiastic coverage of Ratana’s ‘world tour’ plans and the formation of the Kotahitanga Bank. Meanwhile, the relatively straightforward arrangements to gain official approval for the Ratana troupe to leave the country were complicated by government fears about Ratana’s motives. The formal application ‘to leave for England to view the exhibition’ was referred to Cabinet. The Honourable J. G. Coates laid out stringent conditions, requiring sufficient funds (£1600) be deposited with the Internal Affairs Department for return fares and accommodation in England.

Cabinet delayed any decision until the last minute. Even after Ratana asked two sitting members of Parliament to try and speed things up as time was running out, he was told again passports would not be issued unless the deposit was made.

The amount was eventually dropped to £1000 and payment made. On 4 April, less than a week before they were to depart, Pita Moko, in announcing the passports had finally been released, complained this was the first Mäori party to travel overseas that had been hobbledby such conditions. He blamed the delays on certain ‘political natives’ who sought to undermine Ratana’s plans.

Then Dr Peter Buck (Te Rangi Hiroa), at the direction of Sir Maui Pomare, the Minister of Health, turned up at Ratana Pä to vaccinate the people and give them a health check. While some claim this was a further stalling tactic, Pomare insisted he was helping the troupe after learning some members were afflicted with hakihaki (itch).

Meanwhile, Ratana and his family visited Mount Taranaki, and beside Te Rere o Kapuni (Dawson Falls) the waterfall of the prophets, he sensed a voice repeating the words of the prophet Titokowaru: ‘Ahakoa iti taku iti ka tu ahau ki te aroaro o nga iwi nunui o te ao. Even though I be but a small tiny nation, I shall stand before the presence of the world’s great nations.’

They moved on to the Parihaka settlement, once the largest Māori village in the country, where the prophet Te Whiti had conducted his peaceful resistance against the government land grab in the late 1870s.

…As Ratana recalled the events of only three decades earlier he was deeply moved. It was near midnight on 18 March, the anniversary of the return to the village by Te Whiti after his release from prison in 1883. The celebrations had died down, and as Ratana looked around he saw an old woman standing by her house. He approached and asked what she was thinking. ‘My boy,’ she said, ‘I am reminiscing upon the prophecy that Whiti and Tohu left behind, “Not until this village, Parihaka, has been reclaimed by the bush and overgrown and not until one surviving old woman is left within this village, that a young child shall come and lift this old woman bearing her into the new revelations of Jehovah, the Living God”.

Ratana’s visit to the waterfall and his encounter with the old woman at the historic village gave him strength and confirmed his plans…