Witi Ihimaera and Steph Matuku discuss creativity and writing for children

Kia ora kōrua, Ariā and the Kūmara God and The Dream Factory were both very popular in my house and with Matariki this week, speaking about stars, dreams and these two books seems especially pertinent.

At the centre of both books is the importance of stories, to our relationship with the natural world in Ariā and the Kūmara God, and to creativity and individuality in The Dream Factory. One is about the presence of stories and what we can learn from them, the other about the absence of stories and how it takes away from life.

When it comes to the absence of stories, the despair many creative people felt during lockdown is the nugget of reality behind The Dream Factory. Is there something to say about how you each fuel and maintain your creativity? Steph, how did creativity come back to you after your experience in the COVID lockdowns?

STEPH: I’m a working writer. Making stuff up is my job. I don’t really have the luxury of writer’s block. 10% is the wondrous exhilaration of inspirational ideas and images spewing forth as pen flies across page, and 90% of it is grind. It’s churning out words even if you’re not really feeling it, or if you’d rather be doing something else. It’s working out plot holes. It’s moving chunks around to best fit the story flow, it’s rewriting and editing and rewriting again. It’s chasing after that 10% exhilaration. I think that’s the difference between those who aspire to write and those who actually do write; writers keep going when it gets hard.

Although the Dream Factory was inspired by lockdown anxiety, and the endless doldrum of every day feeling like the same, I was still writing and still working through it. The characters’ lives in the book came to a standstill, but mine didn’t!

You have both explored the depth of pūrākau and Māori mythology in previous books you’ve written for children. How do you mingle imagination and your own creativity with pūrākau? Are there aspects you consider when you adapt or retell these in your own creative works to give voice to your own imagination and tell the pūrākau’s own story at the same time?

WITI: Kia Ora Erica, ngā mihi Steph, I can’t wait to read The Dream Factory. The title reminds me that much of the source of my own work comes from moemoea and, because I dream in Māori, their pūtake or root comes from pūrākau which are the original dreams of our first storytellers. I think, to answer your question, when I adapt or retell ancient stories, I ask myself “What if.” What if I update the story, what will happen to it? What if I put a girl on the whale, as I did in “The Whale Rider” how will that change the dynamic of the story and the Aō hou? What if a group of young adults discover that the poutama that Tāwhaki (or Tāne) climbed is still there, as they do in “Aria and the Kūmara God”, is that the way they can get to the star Whānui? And that’s enough to free my imagination so that I can make a new pūrākau out of the old.

Most of my books in fact have their pūtake in pūrākau. Tangi is really a retelling of the separation story of Rangi and Papa. Sky Dancer uses the original mythology about how seabirds and the birds of the forest battled it out for possession of the forest; it’s really a story about mana whenua and the Treaty.

STEPH: You cannot separate mythology out from Māori culture. It’s intertwined. One leans on the other. Most of my works also include mythology because it feels natural.

Ngahuia Te Awekotuku’s collection, ‘Ruahine’ includes a short story about Rona. In the traditional telling, Rona is kidnapped by the moon for being disrespectful. In Ngahuia’s story, the moon is a spaceship and the story becomes one of alien abduction. This work was a tremendous turning point in my understanding of mythology. I’d always thought of legends and traditional stories as sacred, and not to be messed with. But I realised, that if you approach them with respect and understanding, you can play, you can imagine, you can interpret, you can expand. You are allowed. This story gave me permission to engage.

I read a comment about my picture book ‘The Eight Gifts Of Te Wheke’ saying it was a retelling of a myth, which is completely untrue. I made it up because I wanted to write a gruesome fairytale like the Brothers Grimm. On one hand I was insulted that they thought I couldn’t make up my own story, but on the other hand, I was flattered they thought it was good enough to be considered a real ancient legend!

While Ariā and the Kūmara God is for older (8+) readers and The Dream Factory aimed at younger children (5–8 years) you have each written for the other age group in previous works (Falling into Rarohenga) (The Little Kōwhai, Razza the Rat, The Whale Rider picture book). Do you need to adapt, to think and write differently when you’re writing for these different age groups?

WITI: I’m not really a writer for young adults as Steph is, she’s fabulous. I’m a writer of adult fiction who in the picture books you mention is trying to write books the way I think they’re supposed to be written for that age group - or by young writers like Steph. I trust my children’s editor to advise me on level of articulation, however, as I find pitching the language, tone, characterisations and politics at that level difficult, being the age that I am now.

What happens to me, however, is that I get an idea - like the one I am using for The Astromancer-Aria and the Kūmara God-The Astromancer’s Successor trilogy - that is so compelling that I have to write it out for whatever age group it wants to talk to, difficult though that may be. In the case of the Astromancer trilogy (and the last book is already written but won’t be published until 2026) the idea was to create a set of imaginative propositions around Matariki. I’m hoping, one day, to write a Māori Lord of the Rings but, well, one only lives so long.

STEPH: I write for different age groups and across mediums because I get bored easily, and it’s fun giving new things a crack. The underlying story themes might be the same for all age groups, but the story that wraps around those will be different depending on your audience. I tend to write about the negative consequences of capitalism a lot. ‘Te Wheke’ is a classic example of that. But so is ‘Flight of the Fantail’ which is a YA book about patupaiarehe as aliens.

I like writing YA because I like being present with my fourteen year old self. And I like writing junior fiction because kids at that age are so accepting of completely wild, fantastical ideas, which is very freeing to write. And I love picture books because for me personally, they’re so tricky. A picture book has to draw on all a writer’s craft techniques – metaphor, poetry, alliteration, rhyme - all the fancy stuff. And in so few words! And you have to write not just for non-readers, or readers who can only pick out a few words, but also for the teachers and parents who have to read the damn book fifty thousand times. A picture book is the hardest thing on earth for me. Very challenging.

Witi, Ariā and the Kūmara God is a sequel – one of the many things the first book was praised for was the deft way you show readers why Ariā behaves the way she does, ‘caring was for those who have been cared for. No one bothered about Ariā.’ Do you approach characterisation or how to explain characters and their motivations any differently when you write for children than you do when you write for adults?

WITI: Actually, writing young adult fiction is teaching me how to be deft - or more deft - in my characterisations overall. This is because in young adult fiction the characters are so exposed, you can’t hide them behind the stylistic devices that adult fiction writers use to build characterisations. You have to be more direct.

I am finding this problematic in my next young adult fiction book, Le Régne de Ta’aroa. The deftness I need is more complex because the book is set in French Polynesia. Not only do I have to provide a deft characterisation for my main character, Kahutia, I also have to make him convincing - he is French, he speaks Tahitian, and apart from linguistics there are other layers of politics, culture and geography, let alone custom, that I know very little about. However, I will have French and Tahitian editors for the book who will help me and the book will most likely be published, first, for the French-speaking market, so I can hide out with the French for a while and away from prying English-speaking eyes. But the French are as critical as Māori about the way interlopers use their reo so, definitely, deft is the word.

Your books are at a different reading level, but both have stunning night sky illustrations and a dreamy quality. The illustrators’ use of colour in both books supports and illuminates the stories. How does it feel, to have somebody else envision your words in pictures?

STEPH: I was very fortunate that Zak Ātea consented to do the illustrations for ‘The Dream Factory’, and that the design team at Huia Publishers knew exactly what they were doing, because my drawing looks like the left-handed scrawl of a lizard. It’s funny, because when I saw the pictures, my reaction was, ‘Of course it looks like that, it’s exactly right.’ It’s a privilege to have someone wrap my words in art. It’s pretty damn cool, actually. I love the colour palette of the book so much.

WITI: Ka tika, I agree with Steph about how much of a privilege it is to have someone wrap your words in art. In my case my illustrator is Izzy (Isobel Te Aho-White). Ours has been a great working relationship. Sometimes, when I would see her illustrations I would think “They’re showing the story I am telling” so then I either take those particular “telling” texts out or else modify them. As they say, a good picture is worth a thousand words. With Aria and the Kūmara Star I am still marvelling at the richness of detail and clever imaginings in Izzy’s work. For instance, on the cover, it looks like Aria has wings but they are really the eyes of the god Whānui looking at her.

Can we talk about why it’s important for Ariā me te Atua o te Kūmara and Te Wheketere Moemoeā – the te reo Māori editions of Ariā and the Kūmara God and The Dream Factory - to be told and how you work with a translator to tell a story? Do you need a shared vision or a chemistry with a translator for the story to come to life on the page?

STEPH: I’m very lucky to have a Māori publisher behind me. Huia has always been extremely supportive of my work. They have registered translators on staff who work closely with the rest of the editorial team. My knowledge of te reo is fairly minimal, so I’m glad they have the expertise to do that. When they told me one of my first books, ’Whetū Toa and the Magician’ was going to be translated into te reo Māori, I burst into tears. It was the absolute peak of success for me. I’ve had three translated now, and I really have to stop blubbering about it. Why have books in te reo Māori? Why not more, is the answer.

WITI: Actually I prefer not to have a shared vision with the translator (or illustrator). I don’t know everything and I think if you trust in their tino rangatiratanga and grace, wit, professionalism and artistry, your work becomes amplified in ways you never dreamed of. This happened with the translation of my adult novel Sleeps Standing translated by Hemi Kelly. I still feel so cross that his te reo translation is better than the English original that, one day, I might re-write it based on his translation.

For the Astromancer trilogy, I am extremely lucky to have Heni (Jacob). The chemistry has to be with the words, not with the writer, and Heni was able to crack the English words open, as well as the sentences, and transmute them into kupu and rerenga- wine out of water, pearl out of grit. When The Astromancer won an award for a “best te reo book of the year” they sent the prize money to me but I redirected it to her. Her mahi was pure gold.

By the way I am a student at Takuira for the whole year and have just written my very first story in te reo and translated it into English myself. It’s made me more appreciative of the work of writers in te reo. Ngā mihi, Whaea Sharmain me a mātou tauira whai i te reo.

Is there a book or a particular pūrākau that was present, that was read or told when you were a child, that was particularly meaningful or that has shaped the stories you want to tell when you write for children?

WITI: Not book, really, but a meeting house, Rongopai. When I was a very young boy it was a living picture book, one that I could walk into, how lucky is that. I still like to envision all my books as meeting houses that a reader can walk into. Or as a person they can hongi. Personally, my book Navigating the Stars is the one I am most proud of when it comes to my exemplifying the incredible richness of pūrākau, the power of moemoea and my gratitude for the people who told me the stories of my ancestors. When you breathe that book in, you also breathe in my Dad and Nani Mini Tupara who were my first storytellers.

STEPH: Not so much when I was very small, although the creation story of Tāne Mahuta separating Rangi and Papa was always intriguing to me. ‘Wāhine Toa – Women of Māori Myth’ by Patricia Grace and Robyn Kahukiwa is one that stands out from my high school days. Again, ‘Ruahine’ by Ngahuia Te Awekotuku was a turning point for me. And I adore Witi Ihimaera’s ‘Navigating the Stars’. He signed my copy which I shall treasure always!

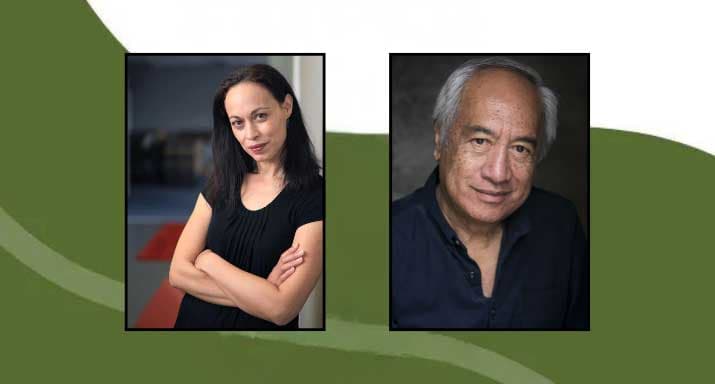

Witi Ihimaera was the first Māori to publish both a book of short stories and a novel, and has published many notable novels, collections of short stories and in 2020 published his substantial nonfiction work, Navigating the Stars. Described by Metro magazine as 'Part oracle, part memoralist,' and 'an inspired voice, weaving many stories together', Ihimaera has also written for stage and screen - including libretti - edited books on the arts and culture, as well as published various works for children.

Steph Matuku (Ngāti Mutunga, Ngāti Tama, Te Atiawa) is a freelance writer from Taranaki. She enjoys writing stories for young people, and her work has appeared on the page, stage and screen. Her first two novels, Flight of the Fantail and Whetū Toa and the Magician were Storylines Notable Books. Whetū Toa and the Magician was a finalist at the 2019 New Zealand Book Awards for Children and Young Adults. In 2021, she was awarded the established Māori writer residency at the Michael King Centre where she worked on a novel about post-apocalyptic climate change.