Review — A Different Light: First Photographs of Aotearoa

Reviewed by David Veart

This book is a companion to a touring exhibition of some of the first photographs taken in Aotearoa New Zealand with images from three of the country’s largest research libraries, Tāmaki Paenga Hira Auckland War Memorial Museum, Alexander Turnbull Library and Hocken Collections Uare Taoka o Hākena. The book is however more than a catalogue, with a series of essays accompanying the images, placing them in context and describing the implications of the changing technology of photography.

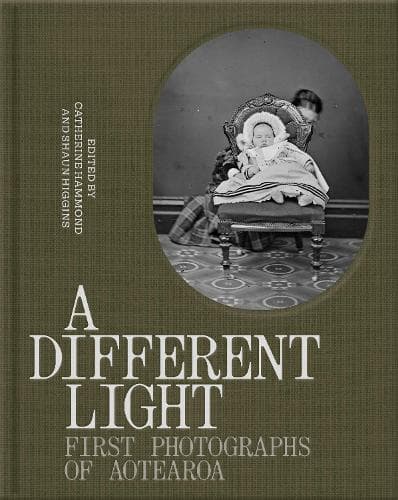

What is immediately apparent is the book’s striking appearance, modelled on a Victorian photo album complete with head and tail bands, ‘marbled’ end papers and a bookmark ribbon. This format is reflected inside with selections of the images ‘mounted’ on black pages echoing the album model. The images and accompanying text are arranged by location with sections on Dunedin, Otago and Auckland, and also thematically examining landscape photography, early amateur images and a fascinating exploration of the ‘Urquhart Album’ which record the ‘Waikato and Taranaki Campaigns’.

One aspect of early photographs is the presence of Māori and in a world where the majority of the inhabitants of Aotearoa New Zealand were Māori this was a frequent occurrence. Angela Wanhalla, in her introduction, discusses the part photography played as part of the colonising process and the relationship of Māori to this technology, where at times Maori were used in some images as colonial set dressing, while other albums were collected by Māori themselves as a ‘visual expression of whakapapa.’

This relationship is further discussed in a chapter by Paul Diamond, examining the a group of images from the ‘Urquhart Album.’ These were taken close to Pōkino, a Maori settlement south east of Auckland. The settlement was on the boundary between Pākehā and Māori controlled land and the year was 1862, a year before the invasion of the Waikato. These photographs show Maori women and children and two young Pākehā men, one of whom was army officer Charles Urquhart, the owner of the album. What we see initially are pictures that record a ‘roadside stall’ where Māori were selling their produce, melons and peaches to Pākehā. But as Diamond tells us, there is much more to see, everything from what people are wearing to ‘evidence of the Māori trading and economic activity that was destroyed by the wars...’

In another rather disturbing image from the same collection, we see a Māori woman captioned only as ‘Annie’ surrounded by Pākehā men, all sitting uncomfortably close to the young woman who is hemmed in by the men’s widespread legs and with Urquhart himself leaning over her. She sits wrapped in her cloak, arms folded. This image has been examined on numerous occasions and Diamond describes the explanations that have been given for the tableau including the idea that the image is some sort of visual joke. I wonder how amusing Annie found it?

From these images rich in human interest we move to the southern part of the motu, Dunedin and Otago, and the horizon widens and photographs of towns and landscapes dominate. The commercial photographers’ work seen in this section provides an interesting counterpoint to the more personal pictures collected for private consumption by people such as Urquhart. Among the southern photographers was William Meluish who between 1860 and 1865 recorded the huge expansion of Dunedin. His images were popular with both citizens as objects of civic pride, and with officialdom, who used them to promote further migration. There are a pair of photographs which demonstrate this. The first is a Meluish albumen silver print of Dunedin and its port, the second the same scene but this time as an engraving for use by the Illustrated London News. The engraving reproduces the photograph accurately, but with the exception that the streets of the town now teem with people, horses, carts all watched over by two imaginary Māori added by the engraver.

The final section ushers in a more domestic world as cameras became simpler and amateurs started to capture pictures of their own choosing. This part had an element of personal revelation for me in that I am familiar with three of the images all of which I have worked with in different ways: one of a man in his vegetable garden used as an illustration for a book, another of Māori gardens at Karaka Bay in Wellington where I gardened 100 years later and the third a Māori kāinga on Hauturu, Little Barrier Island, used to inform an archaeological survey. What I had not known was that they were all associated with the same photographer, Henry Wright, the man standing in his garden.

There are a few things in the book that don’t quite work; the lack of page numbers in the black ‘album’ sections makes referring to photographs from the text clumsy, and the choice of image size is at times puzzling. But these are minor quibbles in a book where the strength lies in the photographs, and there are apparently twice as many here as are included in the exhibition. There are the rigid early portraits of Māori and Pākehā, the wonder of the pink and white terraces, Rangitoto glowing blue in a cyanotype and a record of the people who are remembered only in these images. A Different Light allows us to examine parts of our past in new and intimate ways.

Reviewed by David Veart

Trained as an anthropologist, David Veart worked as a Department of Conservation historian and archaeologist for more than twenty-five years. Veart is author of First Catch Your Weka: A Story of New Zealand Cooking (Auckland University Press, 2008), Digging up the Past: Archaeology for the Young and Curious (Auckland University Press, 2011) and Hello Girls and Boys! A New Zealand Toy Story (Auckland University Press, 2014