Review: A Portrait of Leonardo

Reviewed by Sarah Forster

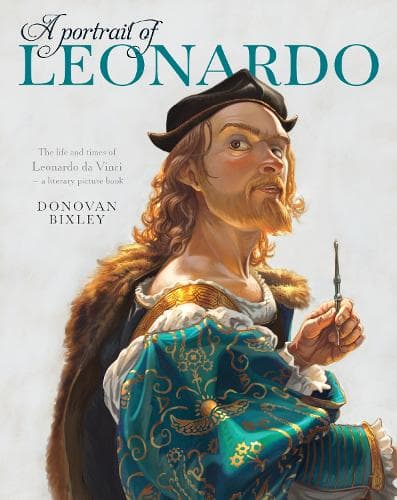

What an astonishing thing Donovan Bixley has achieved in completing his accessible, playful portrait of Leonardo da Vinci after so many years’ research and work.

A Portrait of Leonardo sees Bixley stretch himself as an artist in imagining the world and life of Leonardo da Vinci as it may have looked in the 15th century in Florence and beyond. The illustrations show da Vinci in a dazzling array of aspects: from a distance, from behind, from selfie-stick (kind of!), on horseback, in shadow, in relief.

He brings the world of da Vinci to life by using numerous illustration styles, including at one point using a playful Looky Book style illustration to show how da Vinci incorporated fantasy elements in his art. The people in the illustrations have a remarkable range of expressions on their faces, something characteristic of Bixley’s work.

Bixley explains the turning-points in da Vinci’s life and how he used his architectural, artistic and mechanical genius. Da Vinci was born to the country mistress of a notary and had no formal education before getting an apprenticeship to master craftsman Andrea del Verrocchio. After his apprenticeship, the artist became what we’d know today as a CEO of a creative studio, as Bixley puts it, when he set up his own workshop in Milan in his mid-20s. He quoted and budgeted major works, not just paintings, but armour and costumery, and had a team of artists working with him.

I learned a lot about da Vinci’s personal life—and was happy to see he was able to be openly gay, despite the era in which he lived. While it was, of course, illegal in the 15th century, it was rarely prosecuted in Florence, where he lived for his early life—though this laxity presumably only extended to those with enough influence. I must admit a side-eye to the biographical fact that in 1490, da Vinci had a 10-year-old farmers’ son join his household. While he perhaps wanted to act as a father figure, the same person is later, when aged 20, referred to as his “lover.”

Overall, Bixley succeeds in his aim in this book to make the da Vinci an approachable, if extraordinary person, where his reputation was previously of an aloof genius. In Bixley’s hand, he is a man with a vast scientific interest in everything in the world, no matter how big or small. In the Renaissance period, the arts provided scientists great arenas for scientific practice. Talented engineers—da Vinci included—were involved in the creation of machines that theatre-makers used to create flight, and in creating motion on the stage.

Da Vinci’s famous sketches of flying machines and bicycles were often related to his theatre work. As he learned more about light and natural phenomena, anatomy and what we now call psychology, he used this knowledge in his painting.

“As Leonardo’s portraits became more realistic, they were celebrated for rivalling the real world… This photorealism was a pleasant by-product of Leonardo applying his scientific discoveries to art.”

Something Bixley has cleverly avoided in the book is creating the artworks of the master anew, instead showing them from interesting perspectives with Lady with an Ermine a particularly clever rendition. On his website, he explains this is quite deliberate as he had no wish to go head-to-head with the master.

There are two previous books in this series, about Mozart and Shakespeare. This book complements the series and is similar in style and tone to that of his Shakespeare book.

There is no doubt that our publishing in Aotearoa New Zealand is richer for having these books in it and that this will join his previous two books in international deals thanks to his publisher Upstart Press, who are great champions of his work. The audience for this work is broad but most kids under 10 would struggle with both length and content; I think it would be best for 12+.

Reviewed by Sarah Forster