Review — After the Tampa: From Afghanistan to New Zealand

Reviewed by Graham Reid

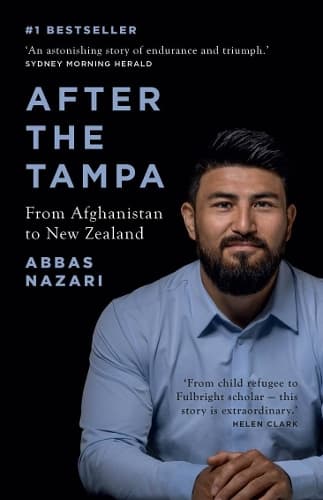

Abbas Nazari’s After the Tampa, rereleased in 2024 with a new cover flashing its bestseller accolades, should be required reading for high school students for its insightful account of the life of migrants in Aotearoa, writes Graham Reid.

Decades ago, at Refugee and Migrant Services in Auckland, I glanced at a map showing that vast territory between Greece and India, lands unfamiliar to most New Zealanders but from which refugees and migrants would increasingly arrive: Iraq, Iran, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Syria.

Someone observed that when these people told their stories, our culture and view of the world would change irrevocably.

True, and many of these people have escaped privation, repression, brutality and war zones of the kind we cannot imagine, even though we witness it nightly, usually with a caution that it “may be upsetting to some viewers”.

Yet these are our fellow citizens: engineers, doctors, cleaners, research scientists, nurses, shopkeepers, civil servants, Uber drivers, architects, teachers. And every one has a story. That of Abbas Nazari is perhaps more remarkable than most.

Today, he’s a graduate of the University of Canterbury and a Fulbright Scholar who received a Master’s in Security Studies from Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service in Washington, D.C.

A long way from being a barely literate child in the remote mountains of Afghanistan, where his family had lived for generations. When the Taliban moved toward their village in 2001, they — being the ethnically different Hazara and Shi’a, both targets for the Sunni fundamentalist militants — fled.

He remembers the uncertain journey to Pakistan, waiting fearfully for months in Quetta, then Karachi before a flight to Jakarta, then the terrifying journey on a barely afloat boat carrying 433 asylum seekers heading for the Australian territory of Christmas Island. With the boat leaking to the point of sinking, they were rescued by the Norwegian container vessel Tampa.

That, however, was far from the end of their troubles. With hindsight and recourse to reports from the time, he tells of how the refugees — starving, ill and terrified — were made to wait a week in appalling and unsanitary conditions, in limbo because the Australian government refused to allow the Tampa to land them on Christmas Island.

Rescue for his family and many others subsequently came with the promise of a home in New Zealand.

“Who is New Zealand?” one man asked.

“Where is he? Let me speak to him!” said another.

Finally, a flight to Auckland and shelter in the Mangere Refugee Resettlement Centre in late September 2001 offered a chance at a new beginning.

Within his story, Nazari pulls back to offer the bigger picture: the history of Afghanistan, the rise of the Taliban, convoluted global politics, demonisation of migrants, this country’s generous treatment of refugees, Afghanistan today and the Christchurch mosque killings.

But he sketches into his writing small yet telling incidents from that childhood of flight and fear: seeing the sea for the first time, tasting his first Coke and piece of chocolate, and in the dark metallic hull of the HMAS Manoora watching television for the first time: the colourful Wiggles and Teletubbies.

More than just the story of his family, After the Tampa is a compelling, plainly written book which should be in the hands of high school students for its gripping narrative and illustration of the value migrants place on education, a luxury few in Afghanistan enjoyed.

In his introduction, Nazari, who learned the alphabet in Mangere, writes: “It is the story of every refugee who has been desperate enough to pack up everything, leave home and friends, and set off into an unknown future. I hope that as you read it, you are prompted to think about their plight”.

Simple sentences here are freighted with meaning, which can give the reader pause. Like this, delivered without irony at the midpoint, after travel and tribulation from Sungjoy in the foothills of the Hindu Kush to arriving in flat and unfamiliar Christchurch.

“Paradise was a state house on Ballantyne Avenue in Upper Riccarton…”

Reviewed by Graham Reid