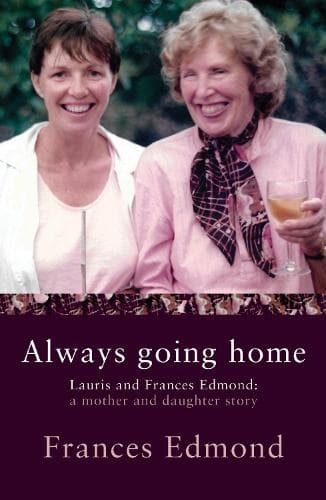

Review: Always Going Home: Lauris and Frances Edmond: A mother and daughter story

Reviewed by Siobhan Harvey

Mothers and daughters: the relationship is so complex, intimate and unique, it’s taken on a cultural life form of its own. Type ‘mother daughter relationship’ into a search engine and 400,000,000 results arrive in less than a second. They offer the ardent researcher all the real and perceived complexities of the relationship: the famous, the mythological, the beautiful, the fraught …

Overwhelmingly, true or not, the algorithms serve up the negative and toxic first, in a way which they don’t if you type in ‘mother son relationships’, wherein healthiness is one of the most dominant adjectives featured in the top results. Gender bias? Gender truth?

The answer, which is more nuanced and extensive than anything a robotic search engine and its computational calculations can ever understand is one quested for by author Frances Edmond in her memoir about her famous literary mother, Lauris, Always Going Home. The book’s subtitle, ‘Lauris and Frances Edmond: a mother and daughter story’ perfectly encapsulates not only this search but also author’s diligent and moving attempt to undertake the almost impossible feat of distancing herself from bias while chronicling the life of one of New Zealand’s most esteemed and cherished authors. Almost impossible because, as Frances admits early on, this legendary poet and autobiographer, this writer who in life and death has become tagged with a fabled narrative, was also her ‘beloved, complicated, difficult, compelling, impossible but greatly admired mother.’

The fable regarding Lauris? After publishing the first of her 20-plus books, In Middle Air (Pegasus Press, 1975), her age and sex struck a chord with a contemporaneous zeitgeist about women’s place in the world. For here, unlike the cultural pathways permitted men, was a woman who’d sacrificed her creative career aspirations in favour of the socially sanctioned route of bearing and raising children, having to wait until the nest was empty and was 51 before showing the world her undoubted talent. Thereafter she became the archetype of the literary woman who battled the patriarchy to beat the male writers at their own game.

The tension inherent in this portrayal is also the tension inherent in the woman; namely, the conflict between the myths so closely associated with her public persona and the real, personal woman behind the façade. In this, Always Going Home is, in no small part, a narrative motivated and sustained by confronting and dismantling these tensions.

Lauris’ birth in Dannevirke in 1924, childhood and schooling in Hawke’s Bay, her experience of the 1931 Napier earthquake, the war years, marriage to Trevor and raising a family in Okahune, her writing existence and literary friendships: yes, all the terrain covered by a conventional biography is here. But then, so too the darker, more personal elements, like the difficult family secrets kept by Lauris’ cousin and the loss of a child the year of Lauris’ first book.

Moreover, like constant refrains, Lauris’ poems and writings scaffold the life-story elements, connecting experience to the author’s inspiration for her verse. Always too the approach is social and expressive. So that rather than a dry history, Frances constructs a ‘her-story,’ interweaving fact with her mother’s emotional and psychological landscape. The interiorities of family members lives are laid bare, often unflinchingly, in the middle chapters, Daughter to mother: the wheel turns and Love’s green darkness. In the former, the author writes in epistolary form to her mother while evidencing the letters her mother wrote to her during her 20s and 30s. Here, the familial rows, tortured tristes, apparent hypocrisies, feelings of hurt, pain and thanksgiving, things spoken rashly and things regretfully unspoken are charted. While in the latter chapter, Lauris and Trevor’s dysfunctional marriage is exposed and Lauris’ lovers interviewed.

Reading this, one might suspect Always Going Home is an acerbic, derisive and condemnatory read. But Mommy Dearest, the infamous 1976 memoir by Christina Crawford, daughter of seminal movie actress Joan, this book is not. The difference is found in the author’s impulse. Unlike Christina’s haunted perceptions of abuse, Frances frames her narrative in affection, admiration, respect and investigation. Where she places fault, as much of it is found in herself as in her mother. Roused to a defense of Lauris in the face of caustic remarks by Trevor one particularly difficult Christmas, Frances berates herself for not maintaining neutrality towards her parents. Moreover, any criticalness on offer is subsumed by the author’s understanding of the mutual respect, sisterhood, and deep amity her mother forged between herself and others. In Chapter 13, for example, an exchange of letters between Lauris and fellow iconic female poet, Riemke Ensing, is offered, the vital role the two writers had in drawing poetry by New Zealand women into the literary spotlight honored.

Always Going Home is a tender, confronting and clever read. It will be of interest to readers of New Zealand literature as well as those who enjoy biographies and memoirs. It should be seen as a companion to its subject’s three volume autobiography: Hot October, Bonfires in the Rain and The Quick World. So, anyone who finishes Frances’ memoir are encouraged to move onto her mother’s books.

Reviewed by Siobhan Harvey