Review: Āria

Reviewed by Elizabeth Heritage

Āria is the debut poetry collection of Jessica Hinerangi, who is of Ngāti Ruanui, Ngāruahine, Ngāpuhi and Pākehā descent. The toikupu are a mixture of prose poetry and free verse, mostly in English but with frequent use of te reo and progress through three parts: Pōtangotango (darkness), Ahi Kā (home fires), and Manawanui (steadfast). A theme throughout is Hinerangi embracing her Māoritanga and her queerness.

Āria is one of the most profoundly bisexual pukapuka I’ve ever read. An immersive sense of ‘both/and’ permeates the whole work: Māori and Pākehā, land and sea, she and they. Hinerangi defines āria as ‘deep water between two shoals,’ and this idea of being the third thing in between two other things recurs throughout the collection. From the prose poem Dear Tūpuna 1:

I glance starboard to the first face of my Māori grandfather, who peers back at me, uncertain, or very certain, I can never tell, to the second face of my Pākehā grandmother who is bookended between tarot cards and spiked trifle pudding … My bedroom mirror has three sides. The two it took to make me, and the one that shimmers in between.

This also feels very bisexual to me – neither gay nor straight but something in the middle. There is a similar vibe in regard to gender: Hinerangi is takatāpui and uses both she and they pronouns in English. In this way Āria feels akin to Cadence Chung’s Anomalia, another recent collection from a young genderqueer local poet.

Āria is dedicated to ‘any displaced or whakamā mokopuna’ and includes a glossary of kupu Māori. The decision to gloss or not to gloss te reo is politically fraught – last year Alice Te Punga Somerville (Te Āti Awa, Taranaki) released a poetry collection where all the English words were italicised, in order to emphasise the place of English as a colonial language. Here, though, I got the feeling that Hinerangi had included the glossary primarily to welcome in Māori readers.

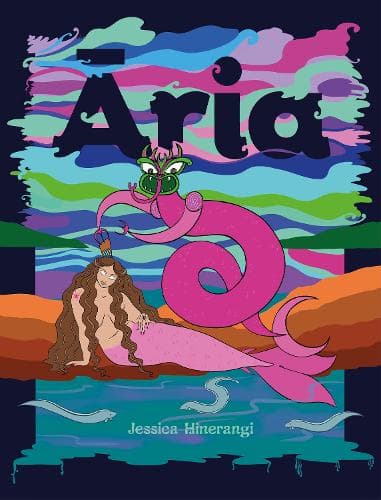

In considering Hinerangi’s work, I keep coming back to colour. Hinerangi is best known for their digital artwork published under the name Māori Mermaid. Their distinctive visual style is full of gentle, swooping lines and often uses pinks and other bright colours. The cover of Āria, created by Hinerangi, features a depiction of a pink sea creature inspired by the marakihau and a mermaid with a pink tail, among a vibrant mix of other colours.

It reminded me of the art of Lissy Cole (Ngāti Hine, Ngāti Kahu) and Rudi Robinson-Cole (Ngāti Kohua, Ngāti Makirangi, Ngāti Paoa, Ngaruahine, Ngāti Tū, Te Arawa), who have created the Wharenui Harikoa using brightly coloured crochet. Hinerangi also explores this interweaving of Māori and Western pop culture and materials in Barbie girl:

I draw moko kauae on my Barbies

and then I make them kiss …

I drive up the coast in my shiny convertible

wearing $2 shop tiki keychains as earrings,

Cali Cool Beach Girl from Õtepoti,

recording my genealogy in my fluffy pink notebook …

‘There are no Māori mermaids,’ another artist says

in my DMs, ‘only marakihau. You’re so colonised.’

Okay? So pick me up and swap my tail out for a skirt

As Āria progresses the voice of the poet moves from uncertainty and shame through rage to love and confidence. The final prose poem, Dear Tūpuna 3, is my favourite:

I escort my colonial self back up the way we came, carefully unbuttoning the pearls on our blouses, shimmying the petticoats to our ankles, stripping the scales from our stockings … It’s not about being clean, it’s about being open.

Āria is the story of a poet who is learning to stand on her own two feet – and swim with their own pink tail.

Reviewed by Elizabeth Heritage