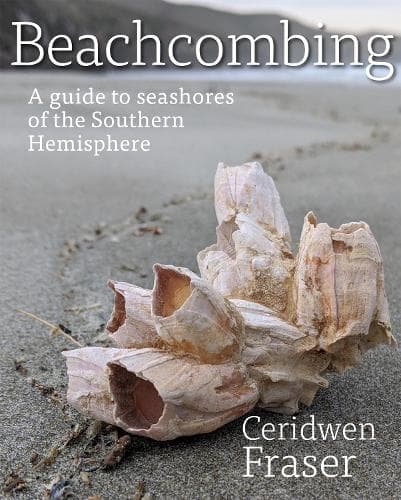

Review: Beachcombing: A guide to the seashores of the Southern Hemisphere

Reviewed by David Gadd

Ceridwen Fraser’s Beachcombing is a book destined to become dog-eared, stained and battered. But I suspect Fraser has a pretty good idea this will be its fate. She herself tells us in the introduction that her’s is a book for browsing, for picking up and putting down, poking into or flicking through when you want to know more about something beachy.

And that is it exactly. A dipping-into book – one to keep in the car glovebox or door pocket, to be dragged out and consulted as necessary when you’re at the beach and have just picked up or spotted something of interest.

In part, this little miscellany of information reads like a theoretical course in the underlying science of the beach. For example, a diagram is provided to understand what constitutes the amplitude of a wave. And langmuir circulation of floating plastics is neatly explained - to the uninitiated, it’s why plastic rubbish clumps together at sea. It is in such moments we know we are safe in the company of Fraser, marine biologist, and can imagine ourselves on a course curated by the associate professor in the Marine Science Department at the University of Otago.

Yet at other times, it is an intensely practical book. Fancy a quick recipe for cockle cooked in kelp or a wakame seaweed salad? Fraser has you covered. But whatever it discusses, Beachcombing is always packed with odd little factoids to keep you interested. Some barnacle penises can extend to more than eight times the animal’s body length apparently. Hmm. There’s even an interesting comparison of southern hemisphere indigenous language words for beach related things, including te reo, two Australian aboriginal languages and one from Chile.

There are, of course, the necessary few pages to help identify shells which inevitably will be amongst the most well-thumbed. I’ve learnt that what I have always called rams horns shells are actually Spirula, a form of cephalopod. Which naturally I should long ago have known and probably did as a 10 year old. Which is the purpose of this delightful, handily soft-cover and compact sized, book. I don’t need to cement such things into my brain or struggle to Google on my phone on a wind-swept remote stretch of beach. I need only remember to bring along a trusty copy of Beachcombing.

The fact this is a book about southern hemisphere beaches in their entirety, not just New Zealand, may seem at first to detract from its practical use, but as Fraser points out, beaches from South America to Australia, are washed by the same currents and there is a great deal of commonality amongst what you will find no matter which country you are in.

There’s an interesting span of all things you’re likely to find on a beach, from flotsam (things that have accidentally found themselves in the water) and jetsam (things that have been deliberately dropped in) to natural treasures such as Ambergris (though reading Fraser’s description of what it is, had decidedly put me off handling it should I ever stumble across it), jelly blobs, seaweed, shells, driftwood and the occasional animal.

Climate change, of course, makes an appearance, and yes, we are a dreadful species in far too many respects, damaging our oceans. But Fraser has a gently optimistic tone. “We’re smart,” she says, “and we have the tools to change things for the better.”

Straggling along a beach, scanning the sand, is a particularly comforting form of exercise/entertainment I’ve always found. Gaining a bit of the insight of Fraser’s expertise, enriches it all the more.

Reviewed by David Gadd