Review: Between Two Worlds

Reviewed by Sarah Ell

Many of us, when we’re young and idealistic, have grand plans of doing something significant and “changing the world.” We might go so far as to sponsor a child or donate money to charity in the wake of a natural disaster, but mostly we just continue to feel bad about everything we see happening on the news and feel powerless to change. It takes a certain type of person to make a true commitment to making a difference and carry it on despite the “real world” pressures of jobs, mortgages and family commitments.

Emma Outteridge is one of those people. Born in Noumea to Kiwi parents who were cruising the Pacific, she grew up in the glitz-and-glamour world of the America’s Cup (her father, Ross Blackman, worked on the New Zealand challenges from the late 1980s, including as chief executive of Team New Zealand in the mid-2000s).

Outteridge could easily have considered a comfortable life of privilege to be her entitlement but the humanitarian conscience which first struck her hard after viewing the film Hotel Rwanda — while working in the incongruous atmosphere of an Aspen ski resort — was to have far-reaching consequences on her life.

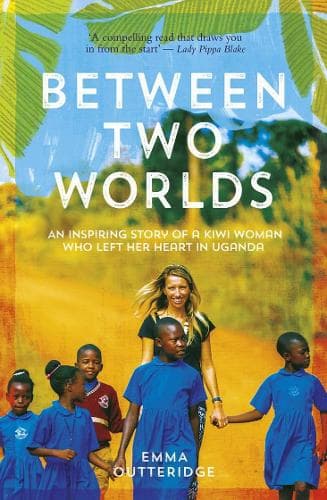

Between Two Worlds tells Outteridge’s story of volunteering at KAASO, a charitable school in Uganda. Although it was initially for a six-month stint, in 2009, the relationships she forged there with those who run the school, and more significantly the students, have turned into a long-term involvement.

She writes of the difficulty she experienced transitioning back into the big-money, champagne-sipping world of grand prix yacht racing and of how she became an advocate to encourage others to sponsor children. Rather than having to do one thing or the other full time, “Slowly it began to dawn on me that I had become a bridge between these two worlds . . . I realised that people were interested, they did give a damn.” From this base, she founded the Kiwi Sponsorships programme, which has funded secondary education for more than 70 Ugandan children.

There are two philosophies which she returns to throughout the book: “With great wealth comes great responsibility” (Bill Gates) and “You can’t do everything, but you can do something.” Outteridge is open about examining her own privilege, how it has impacted her life and later about her mixed feelings on becoming a “yachting wife” when she agrees to give up her own work to travel with her boyfriend (now husband), Australian Olympian and America’s Cup sailor Nathan Outteridge.

She is also up-front about confronting her own “white saviour complex,” the difficulties of integrating Western ideals into a very different society and about her struggle to figure out how to make a long-term difference.

Outteridge could come across as the kind of do-gooding proselytiser you’d cross the road to avoid but fortunately, she can also write. The sections on Uganda, in particular, portraying the daily lives and struggles of the people she works amongst, are without excessive sentiment or condescension; these are obviously people the author respects deeply. Drawing from extensive diaries she kept at the time, she is able to paint an evocative and absorbing picture of the country and its people.

Before her first trip to Africa, Outteridge wrote in her diary, “I have opened my eyes and now I cannot close them. I know that I must act.” She has certainly done that and this record of her physical and emotional journeys is both compelling and inspiring.

Reviewed by Sarah Ell