Review: Blood Matters

Reviewed by Jessie Neilson

This is the second crime novel by renowned playwright, novelist and short story writer Renée. Like her debut, The Wild Card, which was a Ngaio Marsh finalist, it is set in Porohiwi. The gentle pace of life has again been disrupted; insidious forces lurk in the streets. Lockdown has just ended and it is a time of transition and re-establishing relations - or not.

Our protagonist, Puti Derrell, finds herself directly involved and must take the role of detective before murder takes over the town. Small town Porohiwi holds streets you can count. There is a butcher's shop, a supermarket, hairdressers, fish 'n' chippie and the like. While most of the inhabitants are unassuming in lifestyle, on the Other Side of Porohiwi there stand grand homesteads of Governor George Grey's era. Many who dwell in this part of town carry matching colonial pretensions.

Puti could not care less about these rich people. What she focuses on are her nightly running circuits around the shore, where the smell of rosemary and smoke sometimes carries on the air, and her beloved bookshop, Mainly Crime, is found. Yet most of all she cares about her ten-year-old niece, Bella Rose, of whom she is seeking guardianship. Puti is nearly 40 and her older sister and best friend, Ana, has recently died.

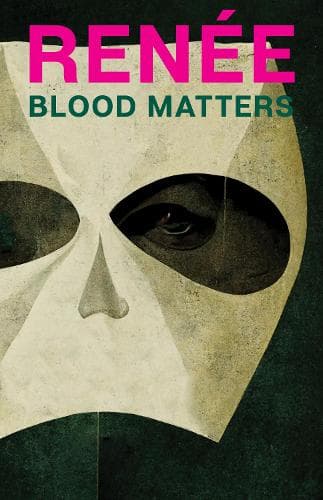

Porohiwi is full of curious characters and dynamics of affection and estrangement. Behind these relationships lie lengthy and complex histories. As is commonplace in a small town, gossip flows. Puti's bookshop becomes one main site of speculations when her much-loathed grandfather, Matthew Derrell, to whom she has not spoken for 30 years, is found dead in gruesome circumstances. The morbid icing on the unpleasant cake is the Judas mask placed upon Matthew's face.

While bully Matthew will not exactly be missed, neither is it acceptable for vigilantes to take retribution. Puti's first aim is to establish Matthew's supposed crime, for the Judas mask reeks overpoweringly of betrayal.

Renée takes the reader through the main streets of the town, introducing us to characters as we amble. There are downtrodden men and dogs with Shakespearean names, the pretentious privileged with their telephone voices, the police on the case, including one termed by Puti a "supercilious shit,” and many others. They hold an abundance of attitudes, some used by Renée to illustrate her experiences of racism and bigotry both as Māori and as takatāpui. Her main method is for the reader to witness snapshots of dialogue between two or three people which immediately reveal their stances, such as one woman's: “I didn't realise you were Māori.” On the whole, Puti tries to put aside these comments, yet occasionally she confronts. This she must soon do with her entire family history, about which we learn, piece by piece.

One curious structural feature is the italicised paragraph which opens each chapter. These paragraphs are taken from the local newspaper, reporting on petty crime and small happenings. They are funny, illustrating the seemingly insignificant dramas between community members which, as resentment builds, take on great importance. The sly nocturnal appropriation of broad beans or "pot" plants are the making or breaking of relations and give us a feeling of the nature of the town.

Blood Matters is a solid read, vivaciously told, outlining any small town in New Zealand through which we may have travelled while on our way to more popular destinations. There are plenty of pleasing images among the mayhem, for instance runners who become part of the shadows, "like melted chocolate folded into soft butter.” Eerily, the Porohiwi Players are opening theatre season with a piece called Masked. Whether for (anti-) viral purposes or for violence, masks take on Biblical significance as horror gathers pace, chasing Puti and her friends through the streets.

Reviewed by Jessie Neilson