Review: Common Ground: Garden histories of Aotearoa

Reviewed by Linda Herrick

Common Ground, a history of humble home gardening in Aotearoa New Zealand, touches upon a period when our suburbs were more highly strung than a row of runner beans.

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, a “City Beautiful” movement measured household gardens as indicators of good citizenship. The days of judgement were nigh, an al fresco equivalent of curtain-twitching.

Whether we’ve become a more mature nation is weighed in the closing chapters of this heartfelt history by Matt Morris, who works at the University of Canterbury and is active in the post-earthquake greening of Christchurch’s Red Zone.

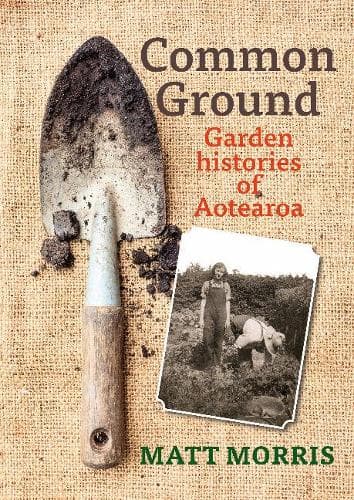

What started out as a PhD thesis on Christchurch gardens broadened into a 10-year nationwide survey which draws upon a vast range of sources. Its academic origins mean its tone is serious and, while including some photos, it is text-heavy. Like gardening itself, it can require a bit of effort but it’s worth it.

Common Ground views our history from a specific perspective, centred on the premise that gardens mirror our lives. Consequently, it chronicles the good, the bad and the downright disgusting.

Morris starts with a brisk overview of traditional Maori food horticulture, dating back at least 600 years before the advent of colonisation. The first European visitors, arriving in the late 1700s, initially praised the “civilised” Maori gardens, trading for vegetables during a brief period of respect followed by the relentless depredations of colonial domination.

New Zealand was advertised as a fertile paradise, with a heavy reliance on imported plant specimens. The sales pitch to new settlers, who would have to grow food to survive, puffed up the “developing myth of colonial productiveness.” Many gardeners kept records, a goldmine for the historian. William Trotter, of Lower Hutt, wrote a fruit and veg diary each day between 1850-61. His account is simple and exhausting, occasionally interceded by an “O God”.

Morris does mention Chinese market gardens, which sprang up in the wake of the gold boom, but observes it’s “a story that has been well told”. The advent of flowers, about 1900, marked a shift. A competitive element crept in (some of which still linger) with the rise of horticultural societies, flower shows and women’s gardening circles.

Gardening was boosted as a morale builder with domestic backyard battles created during the Depression to promote “righteousness”. “City Beautiful” was on the horizon. All this required land. By 1916, home ownership rates reached 50 per cent-plus, an outstanding level of equality but too equal for some who called for gardening to civilise the “unruly classes”.

The early 20th century saw a variety of fads, including native plant crazes (which stripped the natural environment), rock gardens, bitter rows over compost and the disposal of human waste and even a form of eugenics, achieving “racial hygiene” via eating quality vegs. From the 1920s, access to toxic chemicals - most notably, the commonly used DDT - liberated some alarming instincts where weeds, insects and birds were targeted. “Cocky”, writing to the Press in 1950, advocated putting out poisoned water for birds.

The residue from some of these poisons remains in many residential properties, now broken up into subdivisions. Interest in home gardens started to fade in the 1960s but Morris is an optimist. Could we become a nation of self-sufficient gardeners again?

In a chapter called The collapse and renewal of home gardening culture: 1960-2020, he asserts a shared faith in the benefits of community plots, noting that in 2018 the nationwide number had grown to 152. He sees a not-too distant future when New Zealand growers and consumers may need a “food resilience network” - including garden produce - to gain independence from the global, unbalanced supply system.

We need to “harness the potential of gardens,” he argues. “They are as crucial to our wellbeing now as they have ever been.” That’s a concept we could all dig.

Reviewed by Linda Herrick