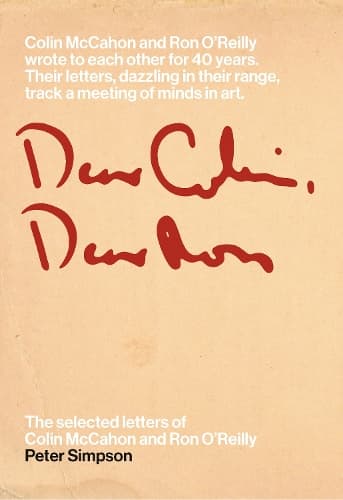

Review — Dear Colin, Dear Ron: The Selected Letters of Colin McCahon and Ron O'Reilly

Reviewed by Graham Reid

Peter Simpson's meticulous research into the life and work of Colin McCahon has already given us the highly readable and insightful surveys There is Only One Direction and Is This The Promised Land?

That there's more to be said is no surprise because frequently Simpson – recipient of the Prime Minister's Award for Literary Achievement in 2017, even before those magisterial books – referred to letters between McCahon and librarian/gallery director Ron O'Reilly, one of the artist's closest friends and lifelong champion of his work.

As early as 1964 O'Reilly wrote in a reference, “I regard Mr. McCahon as the foremost painter in New Zealand”. Although he might critique McCahon's work (“I'm not content with the crucifixion Colin . . . I see no more in it than I did when I first looked at it”), he remained of that belief, collected the artist's work, assisted in acquiring them for libraries, and arranged exhibitions.

For almost four decades from 1938 – McCahon 19, O'Reilly 24 – they corresponded about art, other artists (some of it gossipy and tart), those falling in and out of favour, theatre and classical concerts. They discussed faith and philosophy, reviews and reviewers, practical matters about transferring and displaying the paintings, articles in Landfall or reviews in the Listener, and – in the case of McCahon in the early decades – constant concerns about money and finding a home for his family as he moved about.

It was a struggle but as early as 1946 McCahon wrote, “I can't abide the idea of a settled job”. He knew his calling, although it would be 1971 before he became a full-time painter. He wrestled with his work and feelings about it: “I really don't know how much of what I write about painting I believe myself”; “an exhibition wipes away the past & gives release from one line of work”.

Sometimes one-liners zing out: “Am amazed at the way the rest of the country hardly exists to Aucklanders,” says McCahon, upon settling in Titirangi.

The intensity of the correspondence is ratcheted up in McCahon's final decade as his vision becomes more singular, his thoughts darker and the relationship is sometimes more fractious.

“I felt a tinge of sadness when I talked to my dad about these letters,” writes McCahon's grandson Finn in a short essay at the end. “I saw how family life was at the periphery of everything art”.

That life beyond creativity is noticeably absent in places: O'Reilly's letters in 1944-45 never mention the war; when O'Reilly and his wife Betty are separating it draws scant response from McCahon; the artist's comment, “married life is a mixed blessing & I'm out of practice” appears to go without comment from O'Reilly.

Maybe responses were in letters not published in this generous collection which comes with important annotations, relevant works illustrated and introductory essays on the three chapters. But McCahon's changing tastes and perspectives come through in what seems like real time: In 1949, “Am finding Van Gogh a revelation even from prints” and “am starting to see flat land at last and [am] possessed by it. Me who only painted hills”, to 1980: “I feel very strongly that where I am going is where painting must go”.

The detail and specificity of these letters – with valuable if brief essays by Ron's son Matthew and Finn McCahon-Jones – means they're not for the casual reader although a valuable addition to McCahon scholarship, but the pages illuminate the two central figures, their times, opinions and beliefs.

And most of all, a rare friendship which -- despite sometimes being distant and tested -- was unique and so well documented.

Reviewed by Graham Reid.