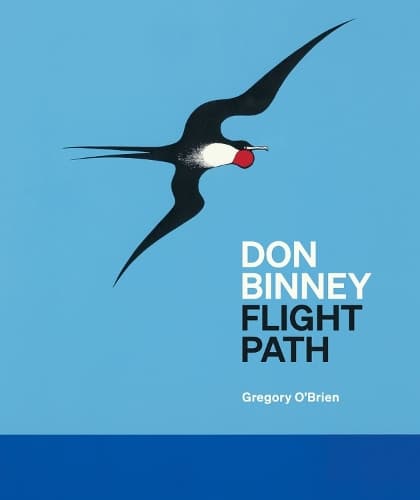

Review: Don Binney: Flight Path

Reviewed by Peter Simpson

Hot on the heels of Francis Pound’s great book on Gordon Walters, Auckland University Press has published another superb art historical monograph, this time on Don Binney, a comparably significant figure in New Zealand art history, by writer and art historian Gregory O’Brien.

Walters the dedicated abstractionist and Binney the dedicated realist are almost polar opposites within the world of painting, committed to antithetical and mutually exclusive tendencies in art but during their lifetimes their careers seemed strangely linked, like two buckets in a well. In the 1960s, Binney was initially ascendant and Walters still virtually unknown; then, in the 1970s and 80s, Walters’ reputation steadily grew while Binney’s just as steadily declined as abstract art gained traction and realist art was deemed (at least in some quarters) passé.

Now, with both artists long departed (Walters died in 1995, Binney in 2012), the passing of time has begun the process of sorting things out, and it is possible for many (myself included) to admire both simultaneously, ‘united in the strife that divided them’ (as T.S. Eliot wrote in Little Gidding). Such, too, is the case with these two superlative books. You do not have to choose between them (unless you are a Book Awards judge). It is a both/and situation and entirely appropriate that they should both have the same publisher.

Don Binney is invariably thought of as primarily a painter of birds but that is only a partial truth. In his own words (the passage is used as an epigraph to the book) he wrote: ‘Although I have used the forms of birds a great deal in my work I am not, as some will say, specifically or especially a “bird painter.” I also paint space, earth, sea, light, and rivers as well as houses, Ratana churches, volcanoes, schoolgirls, islands and roads…What I paint is what I know well.’ To that list one might well add: lakes, beaches, headlands, sand dunes, trees, clouds, graveyards, flowers, animals, dolphins, cloaks, coins and much else besides.

One of the great merits of O’Brien’s book is that while doing full justice to Binney’s legendary birds (his equivalent to Walters’ koru paintings), exploring them to a depth no previous writer has attempted, he also illustrates and discusses many other aspects of his work, thus enriching and subtilizing our understanding of Binney’s full range and releasing him from the strait-jacket of a clichéd identification with a single subject.

The book is divided into six parts and an afterword, plus a detailed (and well-illustrated) chronology and a select bibliography. Part 1, Taking Flight covers childhood and school days and the years of study at Elam, followed by teachers college and school teaching, 1940-62. Crucial to Binney’s development was an early interest in bird watching, stimulated by R.B. Sibson, a teacher at King’s College. Also from age 11 he often stayed at Bethells Beach on Auckland’s West Coast (which he always called Te Henga, having from the start a strong preference for Māori names of places and birds), a location – beach, rocks, headland, sand dunes, skies, swamp, trees, birds – which became crucial to his mature art, even after (in memory) his expulsion from the dwelling he used there after a dispute with the owner in 1977.

Part 2 Between Bird & Headland, 1963-67, covers the years of Binney’s meteoric rise to fame and popularity through a succession of well-received exhibitions at Ikon Gallery and (later) Barry Lett Galleries. It is interesting to note that in his first solo exhibition in 1963 only six of the 25 paintings featured birds, including four of pīpīwharauroa (shining cuckoo), the remainder being landscapes, whereas in 1964 a larger proportion, 15 of 20 paintings, were of native birds: kererū (woodpigeon), kōtare (kingfisher), dotterel, kākā, pīpīwharauroa and others. That is, he evolved into becoming a bird painter.

O’Brien also points out a steady evolution in how Binney depicted bird life; initially the birds wholly dominated the picture plane with only vestigial landscape elements, but increasingly the focus became more on birds within the landscape, as suggested by titles such as Tui over Te Henga (1964) and Kererū over Wainamu (1965). Pictorially there are subtle continuities in shape and colour between bird and landscape, and thematically a growing concern for the relationships between creatures and their environment.

An early environmental activist, Binney was acutely aware of diminishing or otherwise threatened habitat, an implicit concern in such paintings as Sun shall not burn thee by day or moon by night (1966), a stylised depiction of a fernbird (mātātā) in the landscape, the title coming from a biblical psalm – a painting which O’Brien, with characteristic eloquence, describes as ‘a consummate articulation of the idea of safe haven or sanctuary which lies at the heart of the Old Testament Book of Psalms as it does at the conceptual heart of environmentalism.’

Part 3 Offshore, 1968-73, covers a year in Mexico and other parts of Central America , plus a period back in New Zealand, and a sojourn largely in the United Kingdom. Binney’s decision to use an Art Council grant to visit Latin America was unusual but well justified by the results. His exposure to other post-colonial countries and their indigenous cultures deepened and subtilized his understanding of the New Zealand situation as well as leading to some exciting pictures responding to a different natural and built environment, such as Temple to Ehecatl, Calixtlahuaca (1968) and Gulf Coast (1968). Binney’s excellent colour photographs of the region are also well represented. The sea journey home resulted in some spectacular pictures of oceanic birds as in Pacific Frigate Bird I, II, and III which are generously presented in the book’s only fold-out. The trip to England was less productive; a London exhibition at the Commonwealth Gallery was exclusively devoted to pictures of Te Henga subjects painted from memory.

Parts 4 and 5, 1973-85, document the difficult years when Binney became a focus of attack on what was derided as ‘regional realism’ by younger artists and critics more attuned to abstraction and international trends. He suffered a loss of confidence and diversified his practice into other areas – teaching at Elam, photography, collage, still life, paintings based on coins of British sovereigns etc – with only partial success. Fortunately, Part 6, 1986-2012, documents a strong recovery of form and the revisiting of earlier bird-and-landscape centred subjects in the last two decades of his life. O’Brien makes a strong case for these being different from, not lesser than, his earlier successes.

The book is a triumph for author and publisher in all ways except one. The index is surprisingly inadequate. It does not even list Binney’s paintings and other works by name. In other words, if you want to find an illustration of, and references to, say, Kotare over Ratana Church (1963) or Last Flight of the Kokako (1979), or any other painting, you have to trawl through the whole book. The book is bound to be popular, and deservedly so, but if a second edition eventuates, a much expanded index worthy of O’Brien’s outstanding research and writing should be provided.

Reviewed by Peter Simpson