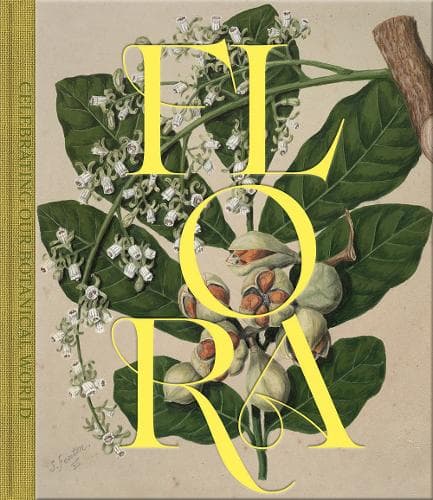

Review: Flora: Celebrating Our Botanical World

Reviewed by Linda Herrick

Flora, Te Papa’s showcase of botanical art from its collections, is huge, sumptuous and gorgeous. The art, spanning at least two centuries and a vast range of multi-media, is sourced from Aotearoa, the Pacific region - and beyond.

Compiled by members of the museum’s curatorial teams, Flora is divided into 13 parts, including a substantial introduction. Each section opens with essays by a range of guest writers plus three of the editors. It’s these essays which provide context to the images, each one an essential guide as you ramble along Flora’s winding paths.

Certain themes emerge strongly but the broad aim of the book, stated in the introduction, is to address a condition known as “plant blindness,” where “many of us struggle to name, describe or even notice the plant species around us. Fortunately, this is curable ... this book is designed to play its part as an antidote.”

Many readers will know New Zealand is being engulfed by unwelcome visitors from outside – exotic weeds - but there’s a phrase in the essay by Te Papa botany curator Leon Perrie for the “Endemic and Unfussy” section which puts the problem into sharp focus: “New Zealand is near or at the top of the world’s weediest places.”

It’s true. Our endemic flora tend to be quiet and unassuming, with tiny flowers, small evergreen leaves and twiggy architecture. They are being engulfed on all fronts by thuggish weeds, human settlement, exotic and thirsty garden plants and rampant wild animals like deer and goats. So we have to work harder to save our native species.

The art works which follow Perrie’s words include packets of seed collected here by missionary-botanist William Colenso in the mid-1800s and a range of impeccable watercolours of native plants, dated 1885, by Sarah Featon, whose work was bought by the Dominion Museum in 1919.

The hibiscus-patterned gown worn by choreographer Parris Goebel at the MTV Awards in New York in 2016 reflects the potent presence of Pacific botanical-cultural references threading through the book.

Another section, Beware the Beast in the Beauty, with an essay by Colin Meurk, whose specialty is ecological restoration, echoes Perrie’s concerns. Meurk notes the pattern of humans “moving around the planet with plants” regardless of the consequences. Hence, New Zealand’s 2500 “indigenes” are battling it out with 35,000 exotic plant species, including 1200 pest plants – a “tsunami of post-colonial baggage.”

Dozens of impressive works appear in this section, including a rare poiawe (poi) from the 1800s; two watercolours from the 1930s by Fanny Richardson, an early advocate of planting native berry bushes to feed birds; a block of “Native Alpine Flora” stamps produced by NZ Post in 2019; and another series of stamps from 1989, showcasing plants like wild ginger, which is now banned. Between those dates, attitudes have changed.

Flora’s Daughters, a section prefaced by an essay by Te Papa historical art curator Rebecca Rice, explores the connection between women and flowers, shining a light on the role of female botanists in early-colonial New Zealand who were often dismissed as “lady painters.”

One of them, Georgina Hetley, wrote and drew the ground-breaking book, The Native Flowers of New Zealand (1888-89), which is featured across two pages, including a rare French edition. Yet she was opposed by Colonial Museum director James Hector, intent on protecting his own work.

Another section, In Untrodden Places, introduced by Te Papa botany curator Heidi Meudt, also salutes female trail-blazers, particularly “the two Lucys,” field botanists Lucy Moore and Lucy Cranwell, whose intrepid careers blossomed from the late 1920s. Their works remain available in our library system, while Festuca luciarum grass is named after them.

Wellington arts writer-poet Arihia Latham (Kāi Tahu, Kāti Māmoe, Waitaha) flips the book’s perspective around in her essay for Ki Te Whaio, Ki Te Ao Mārama. She reminds the reader – and the makers of this book – that westernised museum methods of collecting and categorisation are not appropriate. Te Papa itself is critiqued; its “herbarium catalogue of native plants has been arranged in the traditional European manner.” Dried, pressed, mounted – something vital is missing, asserts Latham. It’s the feel, the taste, the smell, the mauri – the life force. How can that be stored?

The pages that follow include dried specimens on card from the 1880s discovered in an old Roses chocolate box in Te Papa’s botany section in 2020. They are old and flattened but still vivid with colour.

Jessica Hutchings (Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Huirapa, Gujarati), who has a doctorate in environmental studies, brings Flora to a close with an emotional essay appealing for change as we approach “the crossroads of many crises:” “climate change, soil degradation, urban development, accelerated chemical and pesticide use and the ongoing extractive logic.”

I have a small quibble, that the original sources of the images are too sprawling. Given that _Flora’_s essays are so tightly focused on our endemic species, the choice of works could have reflected the same ethos. It’s a bit jarring to read about our vulnerable little flowers and shrubs, then turn the pages and see – as an example - images of their more flamboyant foreign cousins, painted in Britain by British artists, included simply because they are in Te Papa’s collection. There are plenty of exotic flowers in Flora, but they fit because they have an obvious link to Aotearoa and the Pacific through the maker, the setting or the context.

In every other respect, the book is a magnificent specimen.

Reviewed by Linda Herrick