Review: Gordon Walters

Reviewed by Peter Simpson

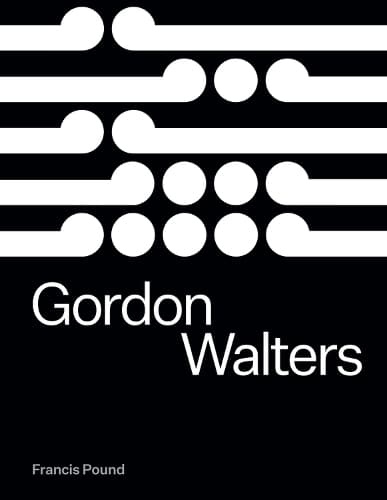

This huge (464 pages), dense, richly illustrated book tells you everything you could possibly want to know about the great New Zealand abstract painter Gordon Walters (1919-95). Art lovers, students and specialists will relish the almost obsessive degree of attention to every detail about Walters’ work.

There is already a considerable literature on Walters including important catalogues, some with substantial texts, such as those by Michael Dunn (1983), William McAloon (1994), and that which accompanied Gordon Walters New Vision (2018), a large survey show. There are also extensive discussions of his work in books with wider themes including Francis Pound’s own The Space Between (1994) and The Invention of New Zealand (2009).

However, there has been no single, comprehensive book about the artist and his work so there is certainly the space and need for a comprehensive general study such as this. Pound (1948-2017) was a gifted art historian and writer who left this book – on which he had been working for many years – unfinished (though substantially complete) at the time of his death about five years ago.

Fortunately, his close friend, Leonard Bell, a former colleague at the University of Auckland and himself a distinguished art historian and writer, has skilfully edited the manuscript and added an invaluable Foreword and Afterword to complete the book. Because of the care and expertise with which this has been done, it doesn’t read at all like an unfinished work but rather as the definitive study which was intended.

The book is especially strong about the years leading up to his breakthrough exhibition at New Vision Gallery, Auckland in 1966 when Walters introduced his mature, immaculate, koru-based abstract paintings to the world. He famously had not exhibited for 17 years because of the animosity he perceived his work would arouse from his commitment to abstraction.

The chronologically arranged chapters contain much writing of great subtlety and even brilliance, covering topics such as Walters’s early figurative, surrealist-influenced work, his excited discovery of ancient Māori rock art with Theo Schoon, his visit to Europe to study abstract art ‘in the flesh,’ and his painstaking efforts during years towards creating a mature personal style that fused Modernist abstraction with elements of Māori and Polynesian design. In Pound’s discussion, to take just one example of Walters’ engagement with the European and American abstract artists who influenced him (Mondrian, Klee, Arp, Capogrossi, Herbin, Stella, Kelly, Judd and many others), he is invariably judicious and persuasive.

Nobody has looked more carefully or closely at Walters’ work and defined so precisely its particular characteristics, including the subtle differences between works within series. Furthermore, the writing is never dull and perfunctory; it is always lively, and often studded with interesting metaphors and anecdotes. Pound also has a great love of footnotes which often contain much fresh and interesting information and the publisher has made the wise decision not to bury these at the back of the book but to include them in the margins of the page on which they occur.

General readers may feel somewhat daunted by the amount of detail but the book is so well illustrated that every small step in the intricate analysis of Walters’ development can be followed easily by those with the patience to do so. I’m sure many will because it is a fascinating story brilliantly and exhaustively told.

In his Foreword, Leonard Bell appositely quotes the great French poet and critic Charles Baudelaire: ‘Criticism must be partial, passionate and political; that is to say it must adopt an exclusive point of view provided always the one adopted opens up the widest horizons.’ Pound’s criticism is of this sort; this is mostly a positive attribute – his writing is always lively, opinionated and engaged – but it does have a downside. He has certain hobbyhorses which he rides indefatigably, such as his advocacy of the superiority of Walters to any other New Zealand artist, his hostility to the preponderance of landscape in New Zealand art and his contempt for the animus (back in the day) of New Zealanders towards Modernism and abstract art. The insistent repetition of these prejudices becomes somewhat wearying even if you happen broadly to agree with him. This reservation aside, the book is superb both in content and production.

With this publication Auckland University Press sustains and builds on its status as a publisher of great art books.

Reviewed by Peter Simpson