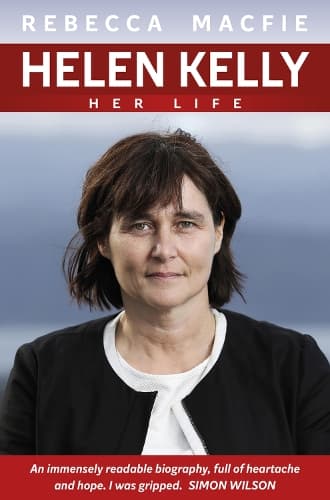

Review: Helen Kelly: Her Life

Reviewed by David Hill

“Was Helen Kelly the Prime Minister that New Zealand never had?” asks the blurb accompanying Rebecca Macfie's splendid biography. Probably not; the trade union leader had more than enough intellect, skills and drive for such a position but, as Macfie makes clear, she would always rather work with private soldiers than with field marshals.

Author of the appropriately-lauded Tragedy at Pike River Mine, Macfie wrote much of this book during 2020's Covid lockdown, a time, as she points out, when the work of so many underpaid, under-unionised New Zealanders became so vital and visible. Compared to the banalities of so many All Black or NZ Idol life stories, Kelly’s is a narrative with gravitas, meticulous detail and commanding emotional force.

It's mostly chronological in structure, stepping across time, then pausing to focus on issues which become dramatic, sometimes disturbing scenes. So, we start with Kelly's childhood in the inner Wellington suburb of Mt Victoria (poignantly yet satisfyingly, she was to spend her final years in the same Shannon Street house) and the influence of her astonishing parents.

Pat and Cath Kelly were committed communists till Soviet imperialism turned them to Labour. They were so intensely political, they make your party subscription or letterbox-dropping seem wan and feeble. Cath spent the day before her daughter's birth handing out party leaflets. Helen went to Clyde Street School and Wellington High, where she seemed “rather square,” then became a primary teacher in Johnsonville: “(she) created a secure, happy, friendly environment where opinions are respected,” said one report.

This eloquent profile of her life is an exceptional tribute to a matching person. It's also a reminder of an unfinished struggle.

But activism wasn't long in coming. At 24, she took up her first union position with the Kindergarten Association / Early Childhood Workers' Union, advocating for better wages and conditions. Almost instantly, her unquenchable sense of fun, plus her “quick, plain and fervent” speech (much like Macfie's own writing) were evident. So were her commitment and ferocious energy.

They were qualities which polarised people. During subsequent years, she was bizarrely accused in Parliament of damaging the trade union cause. Employers claimed that her crusade to make forestry work safer, somehow exploited dead workers and their families. Blogger Cameron Slater mocked her “snivelling, whinging, cloth cap socialist rant.”

Slater's bile was mild, compared to vicious (and mostly anonymous) abuse, death threats, sexual slurs, obscenities that poured in whenever she offended the powerful or indifferent. After her terminal cancer was diagnosed, one of them wrote, “I hope you die a long and painful death.” If only Macfie could have named the creature.

For a short time, Kelly seemed likely to take that potential Prime Ministerial route. In 2007, she planned to stand for Labour in Wellington Central. Instead, she became President of the Council of Trade Unions – and a young chap called Grant Robertson won Wellington Central. Once in the CTU, Kelly hurled herself into issue after issue, supporting Rangitikei meatworkers, university staff, Auckland wharfies, Affco employees. She took up the causes of individuals such as Charanpreet Dhaliwal, the security guard murdered in 2013 on an unsafe site after inadequate training.

You may remember that one. You'll certainly remember some others. She protested the 1991 budget and bills by Ruth Richardson and Bill Birch that cut benefits and “shredded almost 100 years of industrial relations practice.” She fought the decision to drop charges against Pike River bosses. She supported NZ actors during The Hobbit filming, when Peter Jackson claimed he'd need to take production to East Europe if the Kiwis were classified as employees, not contractors, and when John Key's government rushed through legislation to appease Warner Bros. If my own lefty sympathies glint in those sentences, then so do Macfie's during her book – but only enough to make it heartfelt and compelling.

This is a scholarly work as well as an engaging one. There are 50-plus pages of notes and indices; a big selection of photos, along with Sharon Murdoch's terrific cartoon of Kelly at the Pearly Gates, demanding better working conditions for St Peter. It's an intimate story as well, rich with small details: Kelly's love for flowers, especially peonies; the staunchness of her partner Steve Hurring; her apparently limitless energy - “her foot would tap all the time.”

Helen Kelly was just 52 when she died in October 2016. She tried never to use “I”, Macfie notes at the very end; it was always “us.... we... our”. This eloquent profile of her life is an exceptional tribute to a matching person. It's also a reminder of an unfinished struggle.

Reviewed by David Hill