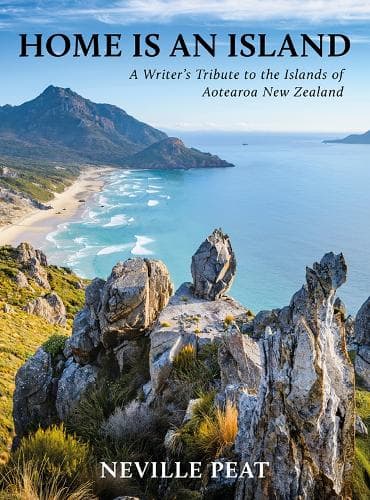

Review: Home Is An Island: A Writer’s Tribute to the Islands of Aotearoa New Zealand

Reviewed by Alison Ballance

Home Is An Island is exactly what the subtitle says: a writer’s tribute to the islands of Aotearoa New Zealand. Author Neville Peat is a Dunedin-based award-winning non-fiction writer with some 40 books to his name, along with plenty of other publications, on subjects covering history, natural history, geography and biography.

After half a century in the writing business, Peat is taking a good long look in the rear vision mirror, revisiting in words some of the many places he has experienced since the late 1960s. The journeys span the tropics to the ice. A love of sailing and the sea took a youthful Peat to Stewart Island/Rakiura and the Chatham Islands/Rēkohu.

His early career saw him move from newspaper reporter to in-house journalist at Scott Base, on Ross Island in Antarctica. A role with New Zealand’s Official Development Assistance programme saw him near the equator recording stories from Tokelau, our furthest and most tropical outpost. A long association with the Department of Conservation led to later visits to island nature sanctuaries such as Tiritiri Matangi, Kāpiti and subantarctic Enderby Island in the Auckland Islands group. The result of a long-standing gig as on-board lecturer on cruise ships visiting Fiordland bears fruit in musings on island-studded Tamatea/Dusky Sound.

Home Is An Island is a collection of essays and stories that the front cover blurb describes as a “narrative of place and belonging.” The connecting theme of the book is islands, which Peat writes “induce powerful emotions, commonly an aching attachment.” He muses on differing perspectives, on how landlubbers “tend to characterise islands as smallish parcels of land separate from mainlands,” while mariners “are more likely to regard the sea as a connecting force rather than an isolating or estranging one.” As the book progresses from his four early experiences, grouped together as New Worlds, to his later conservation-leaning Wild Isles, Peat guides us through the various histories, both human and natural, that define each of his chosen islands.

There are a few first-person tales, including the gripping Thin Ice, in which Peat shares the white-knuckle experience of dog-sledging on the sea ice in Antarctica. Returning to Scott Base on a warm day and despite their caution, Peat and his fellow sledgers found themselves on some very thin ice indeed. One man fell through the slushy ice into the freezing water beneath and it took team work by the other two men and huskies – and some luck – to haul him to safety.

But the book is less memoir and more guide book, an intimate front row seat to Peat in lecturer mode. He writes of nature, early Māori histories, early European exploits and later day rangers and conservationists. We hear, for example, of the building of the first European boat in New Zealand, in Tamatea/Dusky Sound. Of the crayfish boom on 1960s Chatham Islands. Of lighthouse keepers turned island caretakers and restorers, Ray and Barbara Walters.

Peat has a strong sense of perspective, of then and now, and he also shares his thoughts on how he’d like to see conservation evolve in the future, such as better marine protection to link the sea more strongly to nearby protected islands. He is great company; knowledgeable, erudite and he spins a good yarn. So, if you’re planning to visit – either in person or from the virtual comfort of your sofa – the places that Peat writes off, then I highly recommend you read this book. It’ll be like having your own personal tour guide with you, giving plenty of insights into these islands we call home.

Reviewed by Alison Ballance