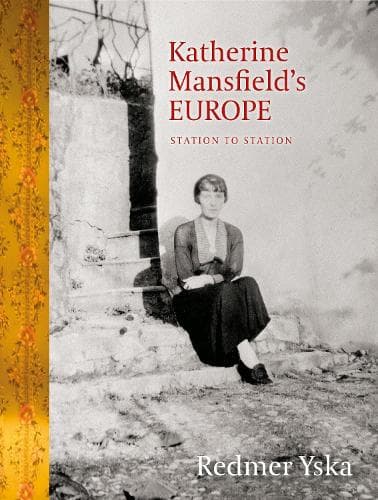

Review: Katherine Mansfield’s Europe: Station to Station

Reviewed by Harry Ricketts

The great literary biographer Richard Holmes describes his approach to writing about the long-dead like this: by “skills and crafts and sensible magic,” he says in Footsteps: Adventures of a Romantic Biographer, it may be possible to bring “alive” the “unattainable past.” For him, he continues, biography was to become ‘a kind of pursuit, a tracking of the physical trail of someone’s path through the past, a following of footsteps. You would never catch them; no, you would never quite catch them. But maybe, if you were lucky, you might write about the pursuit of that fleeting figure in such a way as to bring it alive in the present.’

“You might write about the pursuit of that fleeting figure in such a way as to bring it alive in the present” that sums up what Redmer Yska has attempted, and achieved, in his latest foray into that increasingly populous country, (Katherine) Mansfield Biographia.

Yska begins his pursuit in Fontainebleau where Mansfield died of tuberculosis in January 1923. He then circles back to the start of her periodic nomading around Continental Europe, latterly in search of a miracle cure for her worsening condition. He tracks her “fleeting figure” to Bad Wörishofen, Paris (several times), Bandol, San Remo and Ospedaletti, Menton (naturally), and Valais, until his hunt brings him back full circle to Fontainebleau.

The Bowie-esque undertones of Yska’s subtitle suggest something of the heady mix of his materials and the page-turning pace of the narrative. (It also reminds us how often Mansfield travelled by train.) As we shunt around with Yska and his subject, we are constantly aware of how different (and occasionally similar) life was in the early 20th century. We learn a good deal, for instance, about the mostly quack remedies Mansfield desperately subjected herself to in a world before antibiotics: water treatments, sun-baths, x-rays, Swiss mountain sanitoria, different drug regimes (Yska is especially informative about the highly addictive Mistura Tussi Rubra or Red Cough Mixture she was prescribed) and finally, Gurdjieffian enlightenment.

Crucial to the mix are Yska’s encounters with European Mansfield scholars and devotees, notably Bernard Bosque (“Katherine’s guardian spirit in France”), Henning Hoffman (“Katherine’s literary bloodhound in Germany”) and Roberta Trice (Italian novelist and “lifetime Mansfield admirer”). These become characters in their own right and invaluable guides in Yska’s pursuit. They give him conducted tours of the numinous places where she lodged, suffered and tried to write, several locations now bearing signs and street names in her memory.

I hadn’t properly appreciated before what a revered figure Mansfield has been in France: first, ironically, adopted by the Catholic Far Right in the 1930s as a kind of latter-day saint; later, no less hagiographically, as an embodiment of the doomed artist.

Adroit extracts from the letters and stories are further vital elements in Yska’s ‘reincarnation.’ Early on, he includes various adhesive excerpts from her remarkable first collection, In a German Pension (1911), the imaginative loot she gained from her enforced stay in Bad Wörishofen. Here’s one brilliant snapshot:

‘Here, come and fasten the buckle,” called Herr Brechenmacher. He stood in the kitchen, puffing himself out, the button on his blue uniform shining with an enthusiasm which nothing but official buttons could possibly possess. ‘How do I look?’

Mansfield herself came to reject these sketches, refusing to republish them. (I like their spare, bitchy skewerings and prefer them to all but a handful of the famous later stories, which can be a bit sentimental.) Yska accepts the usual explanation for Mansfield’s refusal to republish; she considered them juvenilia and, admirably, didn’t want to cash in on anti-German feeling during WWI. I wonder, too, whether she simply didn’t want to be reminded of the disastrous pregnancy which caused her to be sent to Bad Wörishofen.

Then there’s this extract from a letter to the long-suffering Ida Baker from Paris, April 1922. It describes fellow hat-shoppers during a rare excursion from the Victoria Palace Hotel: ‘They were like some terrible insect swarm – not ants more like blowflies …. Jack as usual on such occasions would not speak to [me] and became furious.’ We see, half-hear, the shoppers with repellent immediacy.

Just as we see and half-hear Middleton Murry (Jack), here mostly as egregious as ever. (But I want to add, at least, like Kafka’s literary executor, Max Brod, Murry kept everything.) By contrast, Ida emerges in this account as more loyal than exasperating. After all, as Yska reminds us, Mansfield did call her ‘Lesley,’ the female version of the name of her adored brother killed in France in 1915. Mansfield’s nicknames always tell a story.

This is a riveting footsteps-biography which will send readers back to Mansfield’s work with an even sharper sense of wonder that, under these dismaying circumstances, she managed to write anything at all. The lively evocation of the various journeys, past and present (enhanced by the book’s stunning photographs), the extensive archival research, the energising contributions of the modern-day guides: these represent the ‘skills and crafts and sensible magic’ that Yska so persuasively practises to bring back Mansfield’s ‘unattainable past’ and make it ‘alive in the present.’

Reviewed by Harry Ricketts