Review: Life in the Shallows: The Wetlands of Aotearoa New Zealand

Reviewed by David Gadd

Life in the Shallows is one of those immensely rewarding books where almost every page turns up a fascinating fact. For me that can all too often lead to lost time happily ferreting away on book shelves or laptop to learn still more on a particular subject.

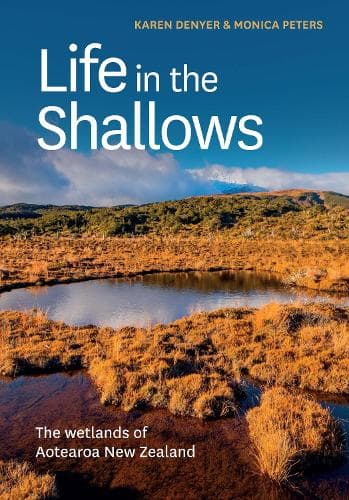

In this way, it has taken m much longer than it should to make my way through Shallows, dedicated to the wetlands of Aotearoa. Which is a disservice to what is an eminently readable book, handily laid out with fact boxes, diagrams, tables and lush photos that make it a delight to spend time with.

Authors Karen Denyer, an ecological consultant of 20 years, and Monica Peters, co-chair of the Citizen Science Association of Aotearoa New Zealand, are well aware of the need to make the subject accessible and they skillfully blend together just enough crunchy, hard science fact to ensure it is an enjoyable experience of widening your knowledge, with conversational writing and a light tone of deprecating Kiwi humour.

Take their admission that we lack the flashy birds of other places and one our most common - yet unknown - wetland birds is the dowdy Mātātā or fernbird which they describe as looking like "a sparrow that's been dragged through a hedge backwards." They quote late Waikato farmer and founder of the National Wetland Trust, Gordon Stephenson, who once described wetlands as our "shy places."

Between them Denyer and Peters convincingly make the case that our wetlands deserve to be far more well-known and - while not wanting to see them trampled by tourism - we should all go visit a local bog, fen or swamp and appreciate them.

Depressingly, we have destroyed 90 per cent of our wetlands; only half those left is protected. That’s a disgrace and needs changing.

Alongside championing the wetland, the book introduces us to a list of scientists and those working to preserve our wetlands in a series of chapters dedicated to differing wetlands, plants, wildlife and endeavours. Paul Champion shares his depth of knowledge of wetland plant life - 523 native wetland plant species and 226 non-native, including the grey willow nominated by Champion as number 1 on the most unwanted pest list.

Although focused on Aotearoa, we visit Antarctica where Dr Clive Howard-Williams reveals the bizarre fact that McMurdo Ice Shelf supports around 1500 square kilometres of wetland, featuring a garishly orange cyanobacteria, surely one of the most long-lived of species on earth.

There are, I warn you, revelations that risk leaving you feeling bewildered, maybe even angry at the stupidity of our current lives. For instance, the work of Dr David Campbell and students at the University of Waikato who study the Kopuatai peatland. That 10,000 hectare of wetland sucks up pesty carbon from the atmosphere - at an eye watering six times the rate of northern hemisphere peat bogs. Yes, we have a miraculous local ecological system doing more good to counter the climate change we caused than any government mandated measure. But what do we do?

Drain peatlands and turn them into carbon producing dairy farms. Of course we do. And Campbell estimates that the total area of drained Waikato peatlands now emit around 2 mega tonnes of carbon dioxide a year - equivalent to 25 per cent of the region's agricultural emissions. It’s enough to make you grind your teeth in frustration.

And yet, you come away from Shallows with hope. One aspect which Denyer and Peters have excelled in is integrating the growing collaboration of mātauranga Māori, the need to appreciate the cultural values of our wetlands. As they say Māori have lived beside and utilised our wetlands for more than 800 years.

The authors usefully illustrate the ongoing relevance of that store of knowledge, as with the work of Yvonne Taura who works at Landcare Research and weaves western and Māori approaches to underpin important restoration work. In this way, with Māori, academic western science, and citizen science working together, we have the potential to both preserve and benefit from our precious wetlands.

It may be called Life in the Shallows but it is a deceptively deep book, leaving you much to ruminate upon.

Reviewed by David Gadd