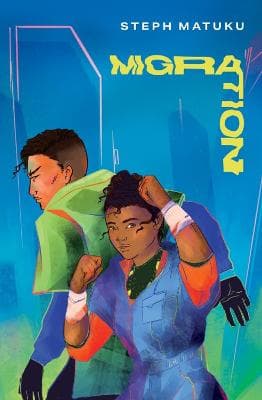

Review: Migration, by Steph Matuku

Reviewed by Tania Roxborogh

On the opening pages of Steph Matuku’s newest novel, Migration, I am confronted with scenes all too familiar from social media and the news: families fleeing for their lives. Children, the elderly, mothers – all desperately trying to find safety. And yet Steph would have written this chapter way before the events we’ve been seeing on our screens. Sadly, this seems to be par for the course of humanity: to destroy first, ask questions later. The difficult truths in Migration can be understood by reading about World War II, Syria, Afghanistan, Palestine: the motivation by the more powerful to take precious things from another culture by force. The how and why of such actions has become almost normalised. Non-fiction is great for transferring information and knowledge; fiction is better for transforming beliefs and behaviours.

The threat of war and the impact of colonization are just the backdrop to an engaging and unputdownable read. As the story progresses, the reader is caught up in the lives of the characters through the wonderfully rendered narrative. The novel shows us the experiences of our point of view character, Farah, as she enters the wānanga military academy as a new recruit. The descriptions of place and character are masterclass. We are introduced to birds, bugs and critters with strange names doing some strange things while reminding me of ‘our’ creatures. For example, in the extract below, Farah could have been looking out over Piha were it not for the pink sand.

“The view almost made up for her irritation. The coastal cliffs, stretched away in both directions, a line of frothy white surf separating the blue ocean from the pink sands of the beach. The breeze brought the sharp scent of salt. The constant movement of the waves below made her feel restless. She was a long way from the placid green gardens of Ngāti Untwa, where the air was always scented with perfume and the birdsong was melodic and sweet. The place hummed with energy…”

Although Migration is set elsewhere (another time or foreign planet), the reality created is completely believable.

There are important lessons, both physical and intuitive, for Farah and us, the reader:

‘Funny how heavy words were when they were imprisoned inside. Letting them out was like freeing a caged bird.’

They are communicated with a light touch. Farah’s self-reflection, her growing skills as an intuitive, and education of histories that underpin her community make us root for her. We share in exhilaration and deep grief. We fist bump mentally when she ‘scores’ a point and get annoyed with other trainees who try to thwart her development.

A traumatic event hardwires a person, their whānau, their community to behave in a specific way. Years go by and the reason for that behaviour might be lost but the kawa and the tikanga that is born from that event remains. The novel reminds us that too many cultures have to factor into the fabric of their society some kind of aggressive force. They must do what is needed to protect and defend their lives and way of life. The need for a military power is a given in this story but seamlessly, Matuku offers a glimpse of an alternative way of being:

“Perhaps instead of trying to force peace through violence, you should consider that peace is best achieved through peace.”

With each new ‘reveal’ of the world of Aowhetū, I inwardly shake my head in awe—how does Matuku come up with this stuff? How does her brain work to create such logical, beautiful, convincing ‘tales’? She’s built an entire ‘laws of physics and science’ and the rules associated with these: all flawlessly constructed and communicated. I totally believe somewhere, sometime, there is a rainbow doorway into which one may step.

Migration has echoes of things I know: the word ‘ngāti’ attributed to different groups of people in the same way as we’d have the British class system, and ‘māma’ and ‘pāpā’ for mum and dad. The wānanga itself is a strict military training academy complete with the same squabbles and hierarchy you’d find in the dorms of many boarding schools. Although not explicitly stated (and it doesn’t need to be), this is a book that has kaupapa Māori mixed all the way through. I recognize many of the tikanga/practices such as pōwhiri and removing shoes before entering a meeting hall.

Under normal circumstances, the welcome ceremony would have taken at least an hour, with speeches and songs and everything planned out to the very last detail. But Vana hadn’t had any time to prepare anything, and the ceremony barely lasted five minutes before the trainees were kicking off their shoes and entering the hall.

Although like The Hunger Games, Migration is way better. Like Maze Runner or Ender’s Game but so much more relevant to our rangatahi. I loved all those other international best sellers but this is superior because it’s a) written by one of our own, b) has a recognisable indigeneity, and c) timeless appeal of relationships and overcoming obstacles. I’ve been telling friends to buy/read/gift this novel because they, like me, will love it for its cracking pace, balance of thrills, humour and sadness, and the brilliant writing. (Perfection. Not one word, phrase, or sentence ill-fitted!) With images like this, teens will love it:

“The narrow space ran behind a row of eating establishments and was home to noisome scrap heaps and porous bins. Drizzles of muck oozed over the cobblestones and into the drains. Farah covered her nose as her boots splashed through stinking puddles, keeping away from the bins lest something small and furry leapt onto her in the dark.”

Migration is funny, real, exciting, incredibly well-written. Treat yourself. You may lose a few days to reading while the dust and laundry gather but it will totally be worth it.

Reviewed by Tania Roxborogh