Review: Nature Boy: The Photography Olaf Petersen

Nature Boy: The Photography of Olaf Petersen probably stands as one of the most thorough and comprehensive monographs on a New Zealand photographer and one hopes it will inspire similar studies of the numerous photographic artist who have helped to forge our visual heritage.

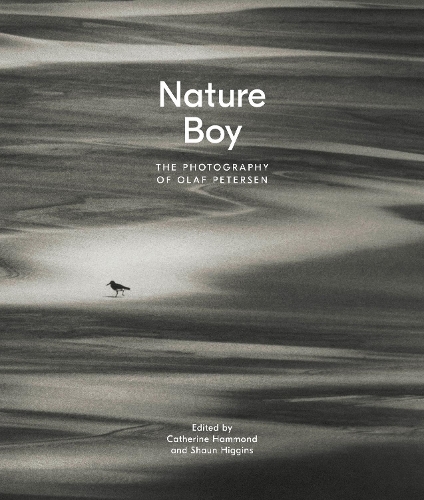

On the ocean side of the Waitakere ranges the raw forces of nature sweeping in from the Tasman Sea generate a palpable sense of connection with the natural world. For Olaf Petersen, Auckland’s West Coast provided an inexhaustible source of inspiration, driving a life-long passion for photographing the wild beauty of this untamed environment.

His achievements are chronicled with archival thoroughness in Nature Boy - a handsomely designed monograph from Auckland University Press which supports an exhibition, now on, at Tāmaki Paenga Hira Auckland War Memorial Museum.

Born in 1915 to Scandinavian immigrant parents and raised on a dairy farm in Swanson, Petersen’s interest in photography was aroused at an early age as he watched his mother processing glass-plate negatives in a makeshift darkroom in their farmhouse pantry.

Shaun Higgins’ biographical essay details how Petersen learnt the craft of photography in the camera clubs which were enormously popular in the post-war years. While enjoying success at Photographic Society competitions and A&P Show exhibitions, he made the transition from enthusiastic hobbyist to self-employed professional, supplying pictures to the Weekly News and photographing weddings and social events for the Swanson community.

Andrew Clifford contextualises Petersen’s photographic work with comparisons to artists like Frank Hofmann and Theo Schoon who pioneered the modernist aesthetic in New Zealand photography. While there are some clear stylistic similarities, Petersen seldom stepped outside of the conventions governing Photographic Society exhibitions. His press work is compared to Marti Friedlander’s documentary studies and though they both produced striking images of kuia with moko kauae, Petersen never really developed the highly personalised viewpoint that makes Friedlander’s photos so distinctive.

The photographic societies supplied the principal means for exhibiting Petersen’s work and his approach to photography is probably best understood within this context. His landscape images, which often exclude the horizon line to emphasise the abstract qualities of line, shape and texture, demonstrate how camera clubs responded to the winds of change blowing through all aspects of 1960s’ New Zealand life. High contrast prints were suddenly all the rage and 19th century pictorial conventions were cast aside as photographic salons absorbed the influence of photographers like Edward Weston and Minor White whose images featured in popular international photographic magazines.

This is not to say Petersen’s work lacks merit. His photos express an intimate affinity with the West Coast environment and his best work, which almost always features sand, deserves to stand alongside our iconic images of the New Zealand landscape.

Writing about his own photography Petersen once commented, ‘‘- got sand on the brain!” He revisited the subject incessantly and accumulated a substantial body of work simply by responding to the changing moods of his local West Coast beaches. The ever-shifting expanses of mineral rich sand provide a dramatic field for the play of light and dark, revealing the intricate textures of wind-sculptured ridges and at times recording the impact of human activity, as shown in the tangled mess of tire tracks left by cars racing towards the once abundant toheroa beds at the northern end of Muriwai.

The vast array of mobile sand dunes surrounding Lake Wainamu, near Te Henga, yielded some of Petersen’s most memorable photos including the remarkable image of three children and a dog walking beneath a towering bank of sand, moulded into rarely seen cylindrical forms which rise above the children like the trees of an enchanted forest.

In a similar vein, Foto Finish shows four children scrambling up the vertiginous face of an enormous dune, their weirdly elongated shadows plummeting across the rhythmically striated surface of the sand. A more pensive mood is evoked in Holiday with two children resting in the sand, their bodies merging into an undulating, softly focused field of delicate grey tones.

These photos will conjure up cherished memories for those who have been lucky enough to enjoy care-free holidays or weekend visits, soaking up the unspoiled beauty of Auckland’s West Coast beaches. The book includes brief memoirs from Sarah Hillary and Sandra Coney, both of whom were photographed by Petersen as children and their recollections build a vivid picture of a colourful character who was deeply embedded in the West Coast community.

Kirstie Ross discusses Petersen’s involvement with New Zealand’s vibrant tramping club sub-culture and records the way he applied his photographic skills to various scientific studies of the natural environment. For many years Petersen was unofficial photographer for the influential Auckland University Field Club and his archive of photographs documenting their numerous field trips will be a valuable resource for New Zealand’s social and scientific history.

Nature Boy probably stands as one of the most thorough and comprehensive monographs on a New Zealand photographer and one hopes it will inspire similar studies of the numerous photographic artist who have helped to forge our visual heritage.

Reviewed by Paul Simei-Barton

Gallery