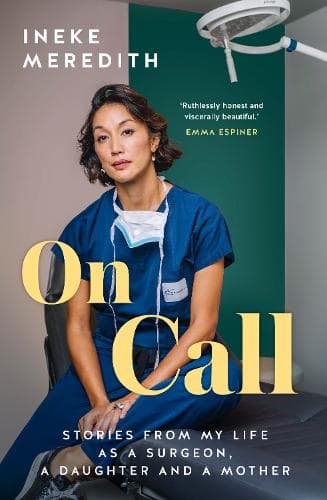

Review — On Call: Stories from my life as a surgeon, a daughter and a mother

Reviewed by Himali McInnes

Operating theatres are not places I remember fondly. Blue-green spaces, fissile with tension and the smell of disinfectant, prowled by territorial scrub nurses ready to pounce on anyone who looked like they didn’t belong (and when you’re a small-fry medical student, as I was at the time, you give off plenty of pick-on-me vibes). Surgeons were the frightening deities around whom the whole room revolved.

On Call, the debut memoir by surgeon Ineke Meredith, is fluidly written and compellingly honest. Being entrusted with another person’s life, plunging your hands into their body cavities while they are in a sedated coma, takes a lot of nerve. A confident exterior belies the very human doctor underneath. Meredith weaves her own story into the narrative, and this perspective (of a female of Samoan heritage in a male-dominated world) adds plenty of resonance. The book is peppered with quick-fire, juicy cases; some are poignant, and some are so absurd they are hilarious (I am still appalled at the builder who tried to fix his own rectal prolapse with a common building product. Good Lord, the things people do).

Surgery has for centuries been a testosterone-heavy profession. There is an enduring perception among patients that male surgeons are somehow more competent. Consultant surgeons who are women are still sometimes mistaken as nurses or even tea ladies. Meredith cites studies showing equal or slightly better outcomes for female surgeons. In my current work as a general practitioner, I make a point of referring patients to female surgeons when I can — I assume they have incredible technique and a point to prove. In recent years, the appalling behaviour of some male surgeons towards their female colleagues has been brought to light. The author has plenty of stories of her own, including being grabbed at by a drunk colleague who hissed that he wanted to fuck her. Balancing all this, of course, are the multitude of caring, competent and equitable male surgeons.

The life of a surgeon is not conducive to their own good health. The hours and hours on call. Rushing back to the theatre to re-open a patient whose vital signs indicate that something has gone wrong inside them. Searching loops of bowel for the tiny hole that is spilling shit where shit should not be. The unbearable shock when patients the same age as you present with metastatic cancer; the way death leers at you because it has won. The endless night shifts and the physical impossibility of managing multiple trauma cases safely and simultaneously. The numb tears when two teenagers who’ve stolen a car and crashed it present with unsurvivable injuries — the way they bleed from their eyes and their ears, the frailty of bodies that should have lived to a ripe old age, the crippling impotence of not being able to save them. Most stories that surgeons have are good ones, Meredith reminds us; but it is the bad ones that stick; it is the ones we lost that haunt us in the still hours of the night.

The most poignant threads in this book are Meredith’s own life story. She becomes a single mum and feels constant guilt at leaving her son with others because she needs to rush to someone else’s bedside. She navigates the ill-health of her Samoan parents, and the spectre of the past sticks its finger in to agitate, especially when she has to juxtapose the frail patient her father has become with the violent, angry man he used to be. This beautifully written memoir deftly paints human flesh and vulnerability onto those God-like creatures we see in scrubs and reminds us that medical professionals do bring their whole selves into each patient encounter.

Reviewed by Himali McInnes

Himali McInnes is a family doctor who works in a busy general practice clinic and an Auckland prison. She writes short stories, essays and flash fiction. She is a constant gardener, a chicken farmer and a beekeeper. Himali adores dogs and books.