Review: Paku Manu Ariki Whakatakapōkai

Reviewed by Dionne Christian

Kids say the funniest – and sometimes canniest, most profound – things. It’s a smart parent who writes or records these for posterity and an even smarter one who turns them into an amusing, clever and insightful book that will make young and old alike pause and reflect.

Michaela Keeble, a writer from Pari-ā-rua (Porirua), has turned the things her youngest son Kerehi Grace (Ngāti Toa Rangatira, Ngāti Porou), now 10, has said to her into dialogue in Paku Manu Ariki Whakatakapōkai which opens with the indomitable young protagonist introducing themself to readers:

Kia ora!

My name is

Paku Manu Ariki Whakatakapōkai.

You can call me

Paku Manu Ariki Whakatakapōkai.

From then on, the youngster is in direct conversation with us, riffing on everything from birth:

When I was born, everything was born.

Everything was born at the same time as me.

To death:

I know there are many ways to die.

If your best friend dies, you will probably die.

If your best friend leaves you,

you will also probably die.

Sometimes I feel so sad I think I’ll die.

This kid is clearly trying to make sense of the world and their place in it. Because they speak straight to us, and are unflinching in expressing opinions, you can quickly build a kind of relationship with Paku Manu Ariki Whakatakapōkai. Sometimes you might smile; sometimes you might feel uncomfortable (but I was happy to sit in this place, contemplating the world’s contradictions and hypocrisies as seen by a seven-year-old).

If you’re reading this with tamariki, it’s bound to be a conversation starter. That’s a good thing given the depth and breadth of “stuff” that Paku Manu Ariki Whakatakapōkai unpacks and the feelings this provokes. Because it’s laced with humour and is a deeper read than it may appear, conversations that arise aren’t likely to feel as forced as they might if we were reading a book with kids that was explicit in its messages about feelings (and the need for them to moderate these accordingly; at least, accordingly to adults and other authority figures).

Paku Manu Ariki Whakatakapōkai is unapologetically unique and questioning, challenging rules and regulations. I wasn’t surprised to learn that among other interpretations, Paku Manu Ariki Whakatakapōkai can mean Little Supreme Commander.

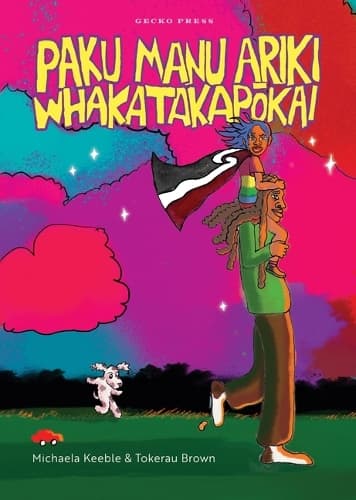

So, that’s the gist of the narrative but Paku Manu Ariki Whakatakapōkai – philosophical, smart and wry – really comes into its own because of its illustrations. Astonishingly, Tokerau Brown (Rarotongan/ Cook Islands Māori) has never illustrated a book before although he codirects an experimental Māori Pasifika Art Gallery in Auckland’s Onehunga and works as an animator.

Brown’s drawings have a cartoonish quality to them – and I mean that as a compliment – and almost swagger off the page. They’re neon bright, matching Paku Manu Ariki Whakatakapōkai’s vim and vigour. The longer you look at them, the more you’ll see.

Keeble says Paku Manu Ariki Whakatakapōkai is a book “for kids who may not find their quirky large families or their senses of humour or the ancestral forces that fuel their lives in other kids’ books at the library or in school.”

I wholeheartedly agree and reckon this makes Paku Manu Ariki Whakatakapōkai an even more relevant read. Funny, canny and profound, it’s one of the best and brightest kids’ books of 2023.

Reviewed by Dionne Christian