Review: Raiment: a memoir

Reviewed by Siobhan Harvey

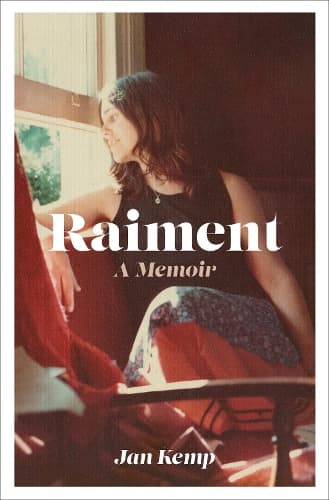

There’s a poetic delicacy about New Zealand author Jan Kemp’s new memoir, Raiment. From its narrative voice to its revivification of Aotearoa in the early 1970s, from its active embracement of authorial verses to its beautiful production, this is a book which evokes Kemp’s truth in a tender, lyrical manner while also reminding us about a history (or should that be her-story) in some ways thankfully lost and in others sadly still far too relevant.

Ultimately, in all this, Raiment seduces us with its historical reenactments and leaves us eager to the next instalment of a life bravely lived by a woman who, in the poetic adage of the time, took the path less followed.

This latter statement is affirmed by the titular word. Raiment is defined as clothing or attire. Here, its use as title arises from the book’s opening quote: a biblical passage, Matthew 6: 28-29 in which raiment, the need for it and its place in people’s lives, is offered as part of a meditation upon worldly versus spiritual adornments. By placing raiment at the centre of her memoir, Kemp uses this philosophical consideration as a guiding metaphor in the recount of her past.

Her early years growing up in insular Morrinsville; her high school education in Howick; her days of intellectual pursuits and forging lifelong friendships undertaking undergraduate and postgraduate degrees at Auckland University; a failed marriage; a failed conception; attempts at a teaching life: all this and more is described by the author across the course of her first 25 years detailed in the book. The results offer a sometimes stark, sometimes stimulating insight into the times, the country and the communal mindset being scrutinized.

In graceful prose, Kemp balances the barriers she faced (the proprieties of marriage and a suitable career) with the headiness she finds in studying, and more importantly, writing texts. For it is her inability to deny her need to write poetry which allows her to negate other weighty demands upon her arising from society, family and tradition. If for Kemp the triumph is the affirmation of poetry as an indelible part of her being, this victory is also cleverly examined – ergo, the raiment symbolism running through the book – as a personal, feminist bucking of the pressures to adorn her existence in consumerist frills and customs befitting her gender.

The era evoked by Kemp in Raiment is one, she astutely reminds the reader, not entirely lost. The experiences, people, morals and politics might have passed but some similarities endure. The prevailing nature of some of the elements Kemp exposes in her work are perhaps most acutely realized in her interrogation of the world closest to her heart: the literary.

There are many mentioned who remain relevant today: Murray Edmond, the Jackson family, Riemke Ensing et al. But set against discussion of these prominent writers and their warm friendships, Kemp also scaffolds the difficulties faced by a woman writer at a time when an older generation of male authors acted as literary gatekeepers enforcing their way of writing as the standard.

As one of the first women to break free of the patriarchal writerly straitjacket in Aotearoa during these times, Kemp’s discussion of the ways of thinking and writing illustrates what a rebel and pioneer she was. But reading about these matters also reminded this outsider-writer that some things haven’t changed. The names, opportunities and literary politics might have altered but the ability of one or two people to accrue power and influence over others and, therein form nepotistic cliques which reward the few, their allies and hangers-on, while disenfranchising, ostracising and silencing the majority endures in literature here as elsewhere.

For its perceptiveness, revelation, introspection, subtle prose and occasional poems, Jan Kemp’s Raiment is an accomplished, necessary read. As a first instalment in a life still being richly mapped, it promises future instalments this reviewer can’t wait to read.

Reviewed by Siobhan Harvey