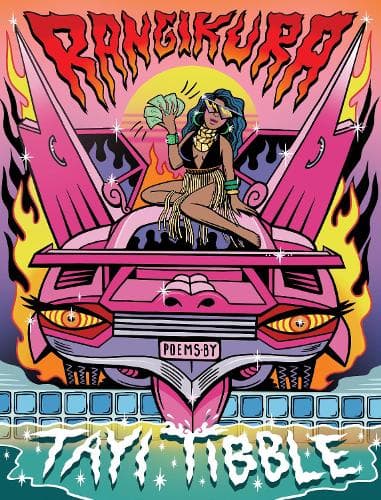

Review: Rangikura

Reviewed by Kiri Piahana-Wong

I roto i tā Tayi Tibble, i a Rangikura, ka tōia mai te tūmataiti ki waho. Ka noho te kiripuaki matua i te ao o te puta ki te pāpara, te kuhu kākahu papai, te inu, te moemoeā, te momi, te hautū waka, te moe ki tō wai rā, te tahu ahi hoki: “Casting our ships full of wish into the sky.” Me uaua ka kitea he pāpā, he māmā e kawe ana i te mānuka, he kōhine kiri parauri e whai ana i tētahi tāne hei toa mōna, he taitama kiri parauri hoki e tāmia ana e ngā pirihimana, ā, katoa rātou e pohara ana. He rotarota hātepe a Can I still Come Crash at Yours? e kotahi atu nei ki te whakamārama i tēnei ao: ”an iPod with / one working headphone, no working dad at home” me te rārangi e kī nei “The empty Tui winding / down on the floor, the clock stuck on midnight.”

Nā ngā piringa hoa, ngā whakangahau, ngā whakaaweawetanga hoki i kitea ai te pukumahi o te ao o te kaituhi. Kei te kahu o te wai o Rangikura ōna painga, ōna piki, engari kei ōna rētōtanga ngā heke me ngā taumahatanga anō hoki. Ka kitea i ngā mahara o te mamae kua kimi i tētahi "home in my chest". Ka kitea i ngā wheako o te mamae, mā reira e ora ake ai te tangata, me te aha, mā konā e whai ai kia pāngia anō ia e taua mamae. Te rongo i te korenga ōu e whakapono ki a koe anō. Te patu i a koe anō, me te kore i taea e koe tērā te aukati atu.

Ko Rangikura tētahi pukapuka e tōia mai ai te utu o te tāmitanga, i rangona nuitia i te whenua, ki te ao mārama. Hei tā Tibble, i That House: “I developed an early kind of kinship / with all the ways the earth hurt.”

Ka tōaitia tonutia ēnei kaupapa i te wāhanga o waenganui o te pukapuka, i tuhia ki te reo kiri-tuatoru, i te whakatakotoranga o ngā kōrero mō tētahi moepuku maukino, te āhua nei i waenganui i tētahi kōhine kiri parauri e tamariki tonu ana me tētahi tāne kiritea e pakeke ana (ahakoa kāore i āta kīia), mā roto mai i tētahi rāngai rotarota hātepe. Ka pupū ake tēnei āhuatanga i tētahi rūma hōtēra, i ngā kokonga huna hoki o ētahi wharekai: “She doesn’t mind that / the places are ugly and out of the way.” Nā te whakamā i rongo ai i te hinapōuri i tēnei raupapa roa: “meaningless thoughts occur to her about being shamed before she was born, before she even had the chance to do anything wrong.”

Ka kitea te whakamā i ngā taha e rua, e whakapuakina nei i te rotarota whakataki o Rangikura, i a Tohunga:

So at least / when my dress hits the floor / like moulting

bark / your eyes follow /and I can interpret / your fixation as shame. / Are

you sorry?

I te wāhanga tuatoru o te pukapuka ka hoki atu ki te tāera i whakamahia i te wāhanga tuatahi, he whenumitanga o ngā kōwae wātea me ngā rota hātepe e pā ana ki te tōreretanga me te tuakiritanga. Ka whai hoki tēnei wāhanga i te whakaahua o te tahu ahi – te hika, te kanikani, te tahu ahi – e auau nei te kitea i te roanga atu. Mai i Te Araroa:

I come from a line of blazing women

born in the red mouth of mountains

that first kiss the sun. They teach me

to live life for fun.

I’ve always been the kind of girl

too fire to be handled with care.

Kua kīia ngā rotarota a Tibble, he rotarota “whakahihiko”, me te tika hoki o tērā whakaaro, heoi anō, ko te āhuatanga ka titikaha ki taku ngākau nōku e pānui ana i tēnei pukapuka, arā ētahi āhuatanga o te hiahia ki te tahu i ngā mea katoa e rite ana ki te hiahia kia mahea ake te mamae, kia māuru ake hoki ngā taumahatanga. I roto i a Kehua / I used to want to be the bait that caught Te Ika, ka tuhia e ia: “The urge to be a passenger in a vehicle going so fast that / the soul leaves the body and the mind is wiped clean.” Heoi anō, ka pūrangiaho i te rārangi e whai ake nei: “I rarely feel it anymore.”

Heoi anō ērā tūāhuatanga, i tua atu i te kite i te tohu nui o tōna “ngākau hihiko”, ōna pūkenga whakakipakipa, mōhio hoki ki te ao tōrangapū, ko te mamae me te paraheahea e mārama ana i roto o Rangikura, ā, nā ētahi wāhanga o te pukapuka ahau i tōia ai, kaua ki tētahi whakaawenga nui, ki te riri rānei, engari ia ki te tangi. Ki te pānui te tangata i a Rangikura, ka whakamīharo ia i ngā pūkenga nui o Tibble ki te whakatakoto kōrero, ka tangi hoki i te nui o ngā uauatanga e pīkautia tonutia ana e tātou.

Nā Kiri Pahana-Wong tēnei arotakenga

Nā Parekura Pēwhairangi i whakamāori

In Tayi Tibble’s Rangikura, the personal is political. The protagonist inhabits a world of clubbing, dressing up, drinking, fantasising, smoking, driving, crashing, burning: “Casting our ships full of wish into the sky.” Fathers are largely absent, mothers try to hold things together, young brown girls dream of attracting a boyfriend who will save them, young brown boys suffer police profiling and all endure poverty. Can I Still Come Crash at Yours? is a prose poem that pulls no punches describing this life: “an iPod with / one working headphone, no working dad at home” and “The empty Tui winding / down on the floor, the clock stuck on midnight.”

Friendships, partying and distractions pull the author through the daily grind of her existence. But while Rangikura sparkles with glitter and bravado, trauma and hardship lurk just below the surface of the good times. The way the memory of suffering can find “home in my chest.” The way in which the experience of pain can make a person feel more alive, which gives them a reason to seek out more. What it feels like not to trust yourself. What it feels like to be self-destructive and yet not be able to stop.

Rangikura is a book where the damage of colonialism, felt deeply in the whenua, is also played out at a personal level. In That House, Tibble writes: “I developed an early kind of kinship / with all the ways the earth hurt.”

The middle sequence of the book, written in the third person, continues these themes as it charts the course of a destructive affair between what is presumably a young brown woman and older white man (although this is not explicitly stated) through a series of linked prose poems. The affair is played out in hotel rooms and in hidden corners of restaurants: “She doesn’t mind that / the places are ugly and out of the way.” Shame laces this long sequence with a bitter undercurrent: “meaningless thoughts occur to her about being shamed before she was born, before she even had the chance to do anything wrong.”

Shame exists on both sides of the equation, as revealed in Rangikura’s opening poem, Tohunga:

So at least / when my dress hits the floor / like moulting

bark / your eyes follow /and I can interpret / your fixation as shame. / Are

you sorry?

The third section of the book reverts to the same style as the first section with a mixture of free verse and prose poetry exploring desire and identity. This section also further draws on the image of burning – blazing, dancing and starting fires – that recurs throughout. From Te Araroa:

I come from a line of blazing women

born in the red mouth of mountains

that first kiss the sun. They teach me

to live life for fun.

I’ve always been the kind of girl

too fire to be handled with care.

Tibble’s poetry has often been described as “fiery”, and it certainly is that, however what strikes me the most when reading this book is how a desire to burn everything up can also be a desire to obliterate pain and transcend suffering. In Kehua / I used to want to be the bait that caught Te Ika, she writes: “The urge to be a passenger in a vehicle going so fast that / the soul leaves the body and the mind is wiped clean.” Although the next line is a disclaimer: “I rarely feel it anymore.”

Nonetheless, as well as displaying her trademark “fiery,” incendiary and politically-aware qualities, Rangikura also reveals pain and vulnerability, and some sections of the book moved me not to awe or even anger, but to tears. To read Rangikura is to marvel at Tibble’s immense skill with words and cry for all that we still have to carry.

Reviewed by Kiri Piahana-Wong