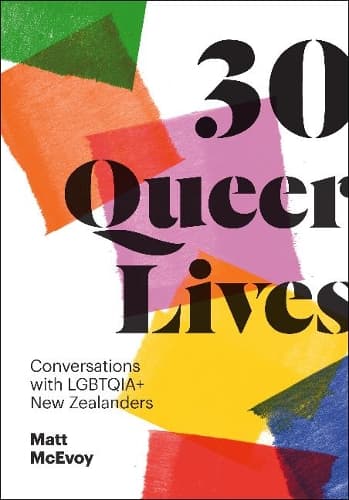

Review: 30 Queer Lives: Conversations with LGBTQIA+ New Zealanders

Reviewed by David Herkt

Matt McEvoy’s 30 Queer Lives: Conversations with LGBTQIA+ New Zealanders offers its readers edited interviews condensed into first-person narratives that encompass the entire range of non-heterosexual intimate experience. The book is written approachably to present a national state-of-play and perspectives, at a particular time in social existence.

Each chapter is illustrated by a monochrome image of its subject and headlined with an alluring summary of its contents. The interviewees are generally public personalities – politicians, entertainers, fashion designers, businesspeople, to categorise a few – as well as a scattering of other more ‘representative’ individuals – a farmer, someone from the defence forces, the academic or school-teacher. Some are immigrants. Most are New Zealand born. There are Māori and Polynesian as well as other ethnicities. They have been carefully selected; boxes are ticked.

Now granted full equality under law, former sexual sub-cultures have come in from the margins but still fresh in the memory of many of men in 30 Queer Lives is a time when their intimate physical expressions were illegal, their social lives hidden, their real lives closeted. However, with the passage Homosexual Law Reform Act of 1986, things changed.

While lesbian women had never faced the same legal hurdle, there were many social obstacles in their lives. The Civil Union Act would lead to full marriage equality for all by 2013. Gender change is a complex matter still in process. While there are few impediments to equal status in 2021, it is a different story socially. Growing up queer is often difficult.

The interviewees in McEvoy’s book range in age from their twenties to their seventies. Their gender definitions are diverse, just as is their preferred sexual nominations. Their personal histories are illuminating.

There is Grant Robertson, New Zealand’s Deputy Prime Minister, Carole Beu, well-known owner of Ponsonby’s Women’s Bookshop, Ramon Te Wake, a Māori transgender woman and TV presenter, Edward Cowley, the gay entertainer better known as Buckwheat, Gareth Farr, composer, Chlöe Swarbrick, queer Green Party MP, Leilani Tominiko, transgender professional wrestling champion, Jonny Rudduck, former Ponsonby pizzeria-owner now ‘gentleman farmer,’ Tom Sainsbury, comedian, and Taupuruariki (Ariki) Brightwell, a takatāpui transgender artist. This is just a sampling.

The details they reveal are frequently fascinating. Grant Robertson’s father, a Presbyterian minister and accountant, had been imprisoned for theft as a public servant. Chlöe Swarbrick relates her everyday battles about holding hands with her partner in public. Edward Cowley describes life coexisting as both Cowley and Buckwheat, with the concomitant complexities of psychology. Ramon Te Wake loves men and considers herself straight. Sawyer Hawker had to gather the courage to approach a military doctor to transition from Sarah to Sawyer.

McEvoy’s book has the avowed ambition of telling stories that “challenge stereotypes and offer courage and hope.”

However, 2021 also saw the simultaneous publication, also by Massey University Press, of Mark Beehre’s A Queer Existence: The lives of young gay men in Aotearoa New Zealand which was similarly a book of rewritten interviews but which focused on 27 gay men who were born and had grown up after Homosexual Law Reform. They were selected in a randomised ‘snow-balling’ way and offered as a record of the consequences of social and political change on a group of representative young men who aren’t well-known or socially recognised. Comparisons between the two books are inevitable.

‘Exemplary lives’ is a category of writing that is more than 2000 years old and includes books devoted to saints and heroes, rulers and artists. They are generally volumes with a purpose. 30 Queer Lives fits squarely in this category. This type of book has made frequent appearances through the last decades of New Zealand LGBTQIA+ publishing.

McEvoy’s book has the intent to proffer examples, as he says, “without interpretation or commentary”. It is, to use a hackneyed word, ‘inspirational’ – or even, perhaps, ‘aspirational’.

On the other hand, Beehre’s A Queer Existence is generally more a social documentary than a catalogue of prominent exemplars. Beehre takes a broad overview and his book will be of historical importance. He also gives his reader a frozen instant of attitudes, autobiography and mores which will have more than temporary relevance. These are not ‘authorised’ or ‘official’ lives but those lived in reality.

The great interest of McEvoy’s 30 Queer Lives is the varied breadth of its subjects’ ages and life-experience. It is readable and frequently the social visibility of its interviewees grants the book the pleasures of a magazine feature article. Self-presentation becomes performative and this too becomes part of the experience as a complicit reader evaluates the act. It lacks the intimacy of A Queer Existence but it offers, in effect, small parables of social triumph to its readers – of survival, struggle, and eventually, it goes without saying, victory.

Two such books in the same publishing year offer an insight into a sexual and gender world in flux. Each volume has its value, each granting an entirely different perspective. Together they provide a glimpse of a changing New Zealand. Each is intended for a different audience, for different purposes, but together they reveal a community still in growth, building on its past, still aiming for the future.

Reviewed by David Herkt