Review: The Surgeon’s Brain

Reviewed by David Herkt

“Here, you see, is the problem, what do I look like in this imagining, what am I to be called?” This is one of the central questions of Oscar Upperton’s The Surgeon’s Brain, a book-length poetic sequence, devoted to the plural lives and times of Dr James Barry, who was probably born Margaret Ann Bulkley in 1789.

Barry obtained his medical degree in Edinburgh and worked as a military surgeon and Inspector General of Hospitals in many countries of the then British Empire – including South Africa, Mauritius, the West Indies, Malta, Corfu and Canada. He conducted one the world’s first successful caesarean births and also advocated for increased hygiene and welfare practices in the hospitals he served or governed. Frequently, he wasn’t popular.

Upon his death, Barry’s servant washed and laid out his body despite explicit instructions that Barry was to be simply wrapped in the sheets in which he had died and then buried. The servant then asked for more money stating that if it wasn’t obtained, she would reveal that Barry wasn’t a man but really a woman with evidence of childbirth. The servant was refused money and spread the story.

It is upon this basis that Upperton has built The Surgeon’s Brain, a 93-page poetic ‘novel.’ It was a bold artistic decision and the book is a stylistic triumph. Contemporary verse is generally the realm of the lyric – or at least the shorter poem. Longer narrative works are a rarity. The poet, Dorothy Porter, has been the most influential Australasian proponent of the long poetic sequence and her The Monkey’s Mask: An Erotic Murder Mystery was a best-selling, multi-awarded “lesbian crime-thriller” in verse. In New Zealand, recent book-length poems include South: An Antarctic Journey by Chris Orsman, He Waiatanui Kia Aroha by Michael O’Leary and Pins by Natalie Morrison.

Upperton’s The Surgeon’s Brain is a life told by angles, fractures and sleights. Barry’s world is broken into shards. In Upperton’s hands, Barry’s character and perspective also have an open shape. Frequently the book’s readers will have to reposition to review and link. There are enigmas, just as there are in the historic record. The style, despite its ostensible apparent prosaic basis, is rhythmed and resounds in the mind with reading. The Surgeon’s Brain is a book which rewards enunciation.

“It is as though I were a ghost and I now have been given form,” reads the back-cover quote from the book’s contents. But is this true? One of the insights of the book is that to strip a human world down to perceptions and fragments is to produce a near-Cubist revisioning of a human biography.

The unitary single voice of traditional writing has gone and just as Barry transitions from Margaret Ann Bulkley to Dr James Barry, so too must the reader’s perspective transition from time to time and place to place. There are fissures and ruptures. The sequence is interrupted. Connections must be remade and restored – or left as openings . . .

The Surgeon’s Brain is not only a narrative — albeit one shattered and shivered to a purpose — it is also gathering of bright human sensations and thoughts. From the feeling of abandonment as a family faces bankruptcy to the stark light, drained colours and strange colonial worlds of South Africa and other outposts of the British Empire, Upperton traverses a long-gone world and its inhabitants in order to revive them. Birds flutter and ship-sounds and maritime routines break upon the reader. Emotional reactions from anger to affection, weariness, wonder and anticipation, all flicker and pass.

Upperton aims high. The Surgeon’s Brain repays rereading. How a reader reacts to the book’s heightened prose poetic and navigates the fascination of its breaks will be crucial. It renders much other contemporary writing on queer subjects somehow quotidian — and in a very minor key — indeed even defining Upperton as a queer writer is almost reductive. He grants access to the strange world that must always be the realm of the Other, someone who is not us, however we define ourselves.

And ‘Definition’ itself is at the very basis of The Surgeon’s Brain. The barrier between one human and another seems insurmountable but Upperton’s vivid slivers and sentences somehow bridge it without creating a false whole. It is an insightful book both in content and style.

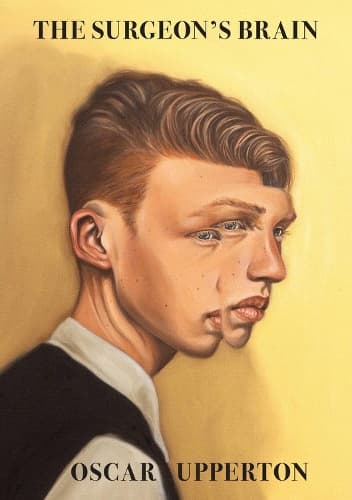

As always, the production by Te Herenga Waka University Press (formerly Victoria University Press) is eye-catching. The cover-illustration by Henrietta Harris is not easily forgotten. More memorable still, however is Upperton’s breath-taking breaking of borders and his cool handling of complexities.

Reviewed by David Herkt