Review: A Queer Existence: The lives of young gay men in Aotearoa New Zealand

Reviewed by David Herkt

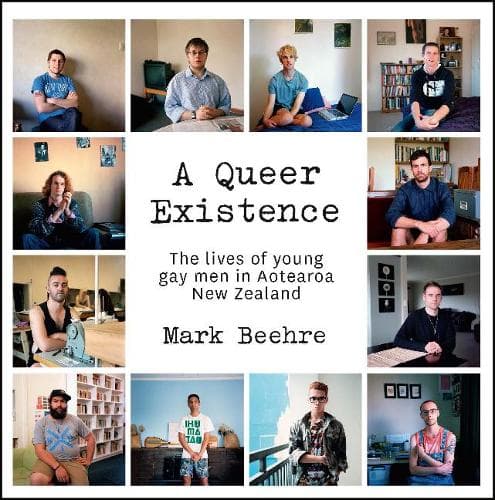

The 27 young gay men in Mark Beehre’s square-format photographs look out upon us from a position of almost preternatural stillness. They might be the objects of our gaze as we examine them — the way they compose themselves, their dress, and their surroundings —but they also scrutinise us and our own assumptions. What do we bring to the encounter? Where do we sit?

Massey University has produced a landmark book, A Queer Existence: The lives of young gay men in Aotearoa New Zealand. It aims to document, in images and interviews, the experiences of a group of gay men who were born after the passage of the 1986 Homosexual Law Reform Act, which decriminalised sex between men.

This was the end of a long process, painfully drawn out. Sexual expression between men had been illegal in New Zealand since 1893. England’s similar Sexual Offences Act, for example, had been repealed in 1967. The process of change in New Zealand was extremely socially divisive. Opposition was vocal and well-organised, and included churches and the Salvation Army. More than 800,000 New Zealanders allegedly signed a petition opposing legal changes but this was rejected by Parliament because of many irregularities including forged signatures. Social progress and the healing of rifts did not follow overnight. A Queer Existence provides ample evidence of breaks and fractures which still resound.

It was an era which is familiar to me. I am 66 years old and have lived with my male partner for 45 years. My life traverses these events. My headmaster attempted to expel me in 1973 for my sexual orientation and I had to fight to remain in secondary school. I joined Auckland Gay Liberation in 1974 and I did most of the research for the Auckland Gay Liberation Submission to the Parliamentary Select Committee on the Repeal of the Crimes Amendment Bill 1974, spending hours with library materials to produce a summary of attitudes, scientific research and law.

To grow up in an environment where same-gender relations do not figure in representation is an odd thing. There are areas of experience which do not seem to have names. To grow up gay at that time meant there was no perceptible alternative to a heterosexual existence, except perhaps a barely understood schoolyard joke.

Somehow attitudes are absorbed, even by their absence. I do not know how I personally assimilated them – I recall no overt examples of prejudice – but, before I was 11, I remember thinking that I should not think of other boys to the extent I did. All of Beehre’s sitters have similar experiences.

A Queer Existence will remain a valuable record of a moment in time. Most obviously, it will provide a resource for young men seeking experiences of comparison but it is also a fine historical record of the individual and social attitudes of the early 21st Century. The images and layout are alluring.

Each of the book’s images is accompanied by an edited first-person interview of an autobiographical and attitudinal nature. They are stories of discovery, of exploration and largely of acceptance. Each of these young men had to discover themselves — and then to find an existence in a social sphere. This is a route those who desire more traditional gender-relationships do not have to undertake.

Inevitably this fact leads to experiences which are important in the creation of character and person. For a long time, I thought of gay teenagers as having to be tougher than their non-gay peers, simply because of the psychological stresses they were required to endure. Not all survive the process undamaged.

Beehre’s interviewees in A Queer Existence are varied. Each brings new facets of the issue into play. Geraint, for instance, could go through his all-boys high school with an awareness of his difference but no real confirmation until – like many of Beehre’s young men – he explored his needs through the internet. By meeting someone with whom he had communicated online, he had his first sexual encounter. His search for identity has now taken him through many forms of non-traditional relationships.

Tongaporutu’s story also provides another example of the book’s value. He is part-Māori and proud of his heritage. It has become an essential part of who he is both as a person and in his career. He has a deep appreciation of history, from Ancient Greece to Polynesia. Obviously well-liked, a basket-ball player and an academic high-achiever, he too had to discover himself and then place himself in a larger cultural context. For Tongaporutu, being Māori has provided an easier context in which to be queer than Pākehā.

A talented and experienced photographer, Beehre’s images are a rich resource. Some are obviously obtained in the sitter’s home, in a bedroom or a lounge in a shared flat. Others are taken in a more neutral environment, a stairwell or a library. They are beautifully composed with much detail and can be read as thoroughly as text. By using a medium-format twin-lens Rolleiflex camera, shooting on film, Beehre’s images gain from the ‘sense of occasion’ such a process enables. They are performances which reveal deeper truths.

The interview texts, too, have many surprises. In a time when, for instance, the words ‘gay’ and ‘lesbian’ do not occur on the website of RainbowYOUTH (the peak-funded body for those in the process of defining their sexual identity), Beehre’s sitters nearly always describe themselves as being ‘gay,’ while acknowledging the range of other words that could be used to define themselves, like queer or takatāpui. Politics is never far from the surface but the interviews in A Queer Existence provide a human baseline without the partisan agendas that dominate many present-day LGBTQIA services.

Beehre’s introduction, sketching recent gay history, is useful. It is a broad but comprehensive overview, recounting many of the political and social currents that contribute to the character of every young gay man born since 1986. One could quarrel with the fact that A Queer Existence generally omits references to the recent ‘culture wars’ that have been so destructive of organisations and events – Auckland Pride, for example – but these are still ongoing debates whose significance is yet to be evaluated.

Religion is one of the surprising issues of concern to Beehre’s sitters. He acknowledges the possibility of the bias of his own religious upbringing, while providing the key to his classic randomised ‘snowballing’ method of selection. He was also surprised how difficult the coming out process remained for many of his interviewees, despite the recent legal and social changes.

A Queer Existence will remain a valuable record of a moment in time. Most obviously, it will provide a resource for young men seeking experiences of comparison but it is also a fine historical record of the individual and social attitudes early 21st Century. The images and layout are alluring.

Beehre’s book also perceives us as we perceive it. We are judged by our reactions. Having grown up in an era where images and autobiographies of this nature did not exist, A Queer Existence documents lives that might not be entirely new to me but are certainly more changed than I could once have hoped. Its existence alone is significant; its perspectives important.

Reviewed by David Herkt