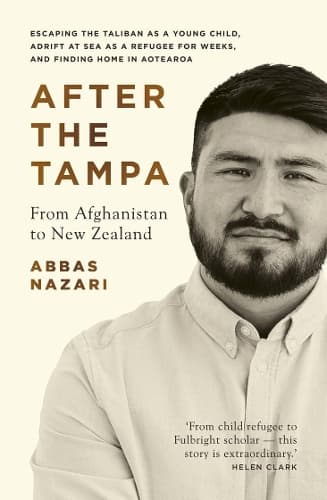

Review: After the Tampa - from Afghanistan to New Zealand

Reviewed by Renata Hopkins

Abbas Nazari’s memoir, After the Tampa, opens with a quote by the Persian poet Rumi: “Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing, there is a field. I’ll meet you there.” The story that follows replaces the adversarial “wrongs” and “rights” that so often fuel debate about refugees with the complexity and depth of lived experience.

In recounting the perilous journey that brought his family from Afghanistan to New Zealand, Nazari offers personal insight into the forces that displace millions from their homes and vividly captures the challenges and triumphs experienced by those rebuilding lives in new lands.

The memoir’s early chapters place Nazari’s recollections of childhood in the isolated highlands of the Hindu Kush alongside an overview of the historic and present day persecution of his people, the Hazara ethnic minority. Happy memories of school, family and village co-exist with the painful realities of life in one of the world’s most impoverished and war-torn countries: a sibling dies shortly after birth when the family is unable to access hospital care for her; schoolmates vanish overnight as families flee the Taliban’s approach. In 2001, Nazari’s father tells his family they leave the next day.

Escape to Pakistan replaces the immediate dangers of warfare with the myriad threats confronting displaced peoples: disease and destitution in refugee camps; hostility and violence fuelled by anti-refugee sentiment and the internal enemies of hopelessness and despair. Desperate to protect his family, Nazari’s father elects to pay people-smugglers for transport to Australia via Indonesia.

Here, no doubt mindful of that impulse to impute “wrongdoing and rightdoing,” Nazari reminds readers that fewer then one per cent of refugees applying for resettlement through official UNHCR channels are successful, a rate at which it would take centuries to address all cases. He asks us to truly consider the circumstances his family faced when deciding if they should board a dangerously unseaworthy boat:

“To stay or go? To endure known misery or to march toward an unknown future? Caught between the endless ocean and an uncertain earth, we chose life. Some kind of future beckoned and desperation powered us to climb aboard.”

So begins the episode around which the memoir hinges: the rescue of 438 refugees by the Norwegian freighter MV Tampa and the international incident that ensued when Australia barred the ship from entering its territorial waters.

Nazari takes the reader behind the headlines, telling the story through the eyes of the seven-year-old he was then. He remembers the fear that became terror when a storm hits the already disintegrating boat. He recalls the miracle of surviving the night and the steadfast determination of the passengers who built a bailing pump from the broken engine and painted SOS on the deck with engine oil. He remembers the moment a small speck is spotted on the horizon, a shape that grows into a ship, “parting the ocean like Moses.”

Alongside these powerful firsthand memories Nazari gives an account of the diplomatic standoff that followed the rescue, the Howard government’s leveraging of growing hostility towards “boat people,” and the subsequent development of the “Pacific Solution” that has seen thousands of refugees and asylum seekers held in offshore detention. Of the Tampa refugees, 302 would become the first inmates detained on Nauru. Others — including Nazari’s family — were offered resettlement in New Zealand. They had never heard of it.

The second half of the memoir explores the challenges and rewards of life in Aotearoa. While many of the events Nazari recalls fall under the heading of “everyday life” — starting school, planting a vegetable garden, gaining a driver’s licence — in the context of resettlement, every step constitutes a huge challenge to overcome, a major milestone to celebrate. At the same time, he reminds us that building a new life also means grieving the one left behind. He is particularly good on the tensions this can create between older migrants and a younger generation more equipped to make this transition.

Latter sections view globally significant events through the unique “hyphenated identity” Nazari has evolved as an Afghan-New Zealander. This includes return trips to his birthplace that see him swing between despair and optimism. He experiences the horror of the March 15 terror attacks from within the Christchurch Muslim community most impacted. Finally, when a Fulbright scholarship prompts a move to Washington during the Trump presidency, he sees xenophobia and racism once again directed at migrants, an experience “eerily reminiscent of the Tampa saga, only this time I was on the outside, looking in.”

Nazari’s capacity to view some of the most urgent issues facing the world from this dual perspective, outside and inside, is his memoir’s key strength. It pays testament to the power of Rumi’s place “beyond ideas,” in which we may meet, and listen, as someone tells their story.

Reviewed by Renata Hopkins

RELATED EVENT

Abbas Nazari appears with Helen Clark at WORD Festival on Saturday 28 August at 11.30am

It is twenty years since a Norwegian cargo ship rescued a sinking fishing boat crammed with more than 400 asylum seekers, only to be turned away from Australia, sparking an international incident. Eventually, New Zealand offered to take 150 of those refugees, including Abbas Nazari and his family.

A child at the time, Abbas now tells his story in After the Tampa, from the Taliban’s brutal rule in Afghanistan, and his family’s desperate search for safety, to Georgetown University in Washington, where he is currently a Fulbright Scholar. He is joined by Helen Clark, Prime Minister at the time, who will discuss the political circumstances around the incident, and whether or not anything has changed. Chaired by journalist Mike McRoberts.