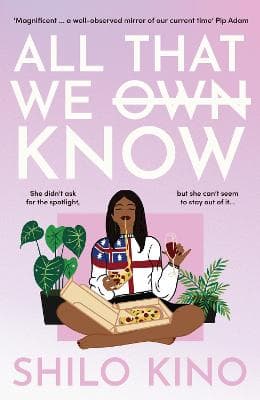

Review: All that We Know

Reviewed by Damien Levi

Read this review in te reo Māori

Making a move away from her young adult debut, award-winning author Shilo Kino (The Pōrangi Boy, 2020) refines her voice for a new adult audience in All That We Know.

Thrust into circumstances she didn’t ask for and doesn’t like, Māreikura Pohe is frustrated and disconnected. She’s attained minor celebrity status online after speaking out about a student at her school doing blackface, her best and only friend Eru is leaving on his Mormon mission to spread the word of the Lord and Māreikura is taking on the heavy task of learning te reo Māori through rumaki.

There is no doubt that this is a story that draws on personal experience. At times it borders on cliche with how relatable the interactions are, like in the opening chapter where Māreikura is accosted by a hōhā aunty at the gates of Waitangi for the crime of not having her reo. 'The woman smirked. There was satisfaction and a hint of superiority in her smirk. No empathy or understanding of a shared colonised past. It told Māreikura, You are less than me. You are not enough.'

With Tāmaki Makaurau as its background, Māreikura’s journey is one that will echo in the hearts and spirits of many young urban Māori—those who have grown up away from their tūrangawaewae, denied the birthright of their reo and who carry the unseen scars of intergenerational trauma.

Māreikura is joined by a fantastic ensemble cast who often challenge our strong-willed protagonist in the same way our friends tell us all the things we know are true but never want to hear.

There’s carefree and chaotic kura mate Jordana, who has a wonderful line in 'Please don’t cancel my babies,' when Māreikura posits the idea that houseplants are colonisation. Kat, the Māori girl-boss girlfriend who knows all the wāhine in town and runs her own company. Troy, a ‘whakahīhī’ tāne raised by four women. And Eru, the absent best friend who 'denies he is gay and says he has ‘same-sex attraction’' due to his Mormon upbringing.

Despite a growing circle of support around her, Māreikura still carries a lot of mamae. Raised by her nan Glennis through whangai, the absence of Māreikura’s mother is felt keenly by both women. Surrounded by Pākehā in their Grey Lynn home, Glennis 'did not want Māreikura to learn te reo Māori. What the hell for?' This decision to keep Māori culture and language from her grandaughter is a point of friction in their relationship. 'I taught your mum. What good did that do? Look where that got her.'

For most of the book it’s quite hard to get on Māreikura’s side. She’s often abrasive and at odds with many of the people in her world, especially the Pākehā. So much so that when her new chaotic kura mate Jordana suggests starting a podcast, Wahine Chats, the first episode tackles the topic of whether Pākehā should learn te reo. This becomes a particular point of contention with her non-Māori classmate Chloe, leading kaiako Whaea Terina to share this incredibly impactful quote about rumaki reo and the role Pākehā can play in preserving te reo Māori.

'Me maumahara koe, ina ka toromi koe, kaore koe I titiro ki te tai te kara ō te taura e whakaora ana I na koe. When you are drowning, it doesn’t matter what colour the rope is.'

Unfortunately this guidance doesn’t sink in with Māreikura, whose ego is bolstered as the podcast grows in popularity, her follower count goes up and the duo start to get sponsorships and award nominations. The external validation starts to get to Māreikura and an echo chamber of toxic, exclusionary thinking is built up around her. Jordana tells her, echoing the opening scene, 'You make people feel shit for being Māori. For being who they are. You’re the gatekeeper now.'

Having imploded her relationships with everyone around her—breaking up with Kat, throwing Troy under the bus on the podcast and fighting with Jordana as a result—Māreikura 'had never felt so vulnerable, so ripped apart. Every single word hurt.'

It’s here that the tentative friendship of Māreikura and Chloe became one of the strongest elements of All That We Know for me. It signified growth and change in Māreikura—a smoothing of the sharp edges being thrust into social media virality had forced her to hone.

Kino brings her characters to life with such skill that they feel real, because in some way they are. In reading her work, I see fragments of my own life and those around me reflected back—urban Māori struggling to find their reo and culture, Pākehā navigating how to be good Te Tiriti partners, burgeoning queers figuring out their relationships and reconciling their faith.

Kino has a clear talent for reflecting contemporary Aotearoa society and balancing its lightness and darkness. All That We Know deals with complex issues both contemporary and historical—from social media justice and internet virality to the pervasive effects of colonisation—but never once does it truly feel oppressive or heavy. In fact, the distinct kindness and humour of Māori shines through, like when Māreikura’s Aunty Lois welcomes her back to the turangawaewae—'You watch girl, you might leave this whare ten kilos heavier with a full puku but at least you’ll have a full heart.'

This book cements Kino as an important voice in contemporary Aotearoa fiction, with a deft ability to pen stories that reflect the lives of audiences who are greatly underserved in our publishing landscape. All That We Know is sure to be a feature on the bookshelves of all your hottest and best-read friends.

Reviewed by Damien Levi