Review: An Indigenous Ocean, by Damon Salesa

Reviewed by Siniva Bennett

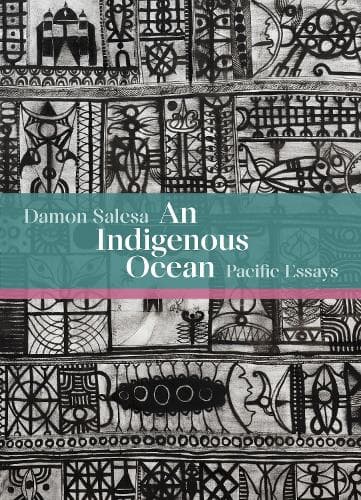

Damon Salesa, the first person of Pacific descent to be a Rhodes Scholar, is currently the Vice Chancellor of Auckland University of Technology. He taught at the University of Michigan for several years before returning to teach in New Zealand at the University of Auckland. His book of fifteen scholarly essays, An Indigenous Ocean, won the Ockham 2024 General Non-Fiction Award, one of the most well-regarded awards in Aotearoa for a non-fiction work. The book features many previously published pieces on Pacific and Samoan history, race, and New Zealand colonisation as well as a newly published piece on Samoan navigation.

As a Samoan raised in the U.S. and once upon a time a graduate student of Pacific Studies, I am always curious to see what emerges from Aotearoa New Zealand, the hub of Pacific arts and letters. I was recently given a copy of An Indigenous Ocean and was intrigued to read it.

In ‘Finding and Forgetting the Way: Navigation and Knowledge in Samoa and Polynesia’, Salesa takes on Samoan navigation and the reasons for waning navigation in Samoa. He counters the tired trope of the natives who forget their culture once they are overwhelmed by colonial ways with evidence of the changing travel needs of Samoans in the 1800s not simply determined by interactions with papalagi outsiders. Salesa’s research of this ‘missing’ piece of Samoan navigation is significant scholarship that explored questions I’ve long wondered about myself. Early in his essay he writes:

“I want to pursue a multiple contextualization of Samoan navigation seeing it within the broader Pacific Island navigational knowledges and within some of the specifics of imperial and colonial encounter. I also want to consider some of the repercussions of using ‘science’ as a framework of inquiry or comparison, less to see whether or not Samoan or Polynesian navigation qualifies and more to explore how the competencies suggested even by these kinds of questions helped define the operations of colonialism and imperialism, and in a broader sense the encounters between western observers and Polynesians.”

Salesa works painstakingly to uncover this history, and I would love my mother and her siblings, well-read but not academics, to explore it. But the essay, like the quote above, is dense: written in a way that will be difficult for many readers outside of an academic context to interpret. I was surprised by this.

Academic writing is a niche style of its own. It may be that academic authors lose sight of this, or if aware of it they might believe they need this language to fully explore the nuance and intricacies of their inquiry. I would argue that they don’t.

Just as Salesa considers repercussions of the framework of science, it seems important to consider the validity of the framework of “traditional” scholarly writing, its limitations, where it came from and who it serves. With Salesa’s latest essay, it’s a missed opportunity to not take a different approach and consider a broader reach and impact. It’s not enough to hold space in the academy or to write for other Pacific scholars. The Harvard professor and New Yorker writer Jill Lepore has famously characterized a limitation of academic writing ‘as a mountain of scholarship behind a moat of dreadful prose.’ Salesa’s writing is not exactly dreadful but the moat dug around his scholarship, with his choice to continue the conventions of academic language in the essay ‘Finding and Forgetting the Way: Navigation and Knowledge in Samoa and Polynesia’, keeps his work from a wider audience. Most of the general public as well as most of the people, his own people, whose history he’s writing about, are on the other side of this moat of academic prose. It’s not merely stylistic to use cumbersome academic language: it reinforces academic conventions that are by nature exclusive, rooted in elitism, often classist and racist.

By contrast, in Salesa’s previous book Island Time he writes more directly and succinctly for a large audience and allows for a more personal and confrontational voice, a voice closer to his own subjectivity, as a critic addressing national shortcomings and continued racial marginalization in New Zealand. The essays in An Indigenous Ocean, critiques and counter narratives to colonial histories and paradigms of the Pacific, are different to this: written largely to be read by Pacific and non-Pacific scholars, and to interrogate narratives created by white academics. But when your work is countering the colonial narrative you can get caught up explaining things to white people. When Salesa writes in ‘Finding and Forgetting the Way’ that, “Pacific Islanders considered the sea not so much as a barrier, but as a connection to other places,” he probably isn’t writing that to inform other Islanders, but we deserve our history to be written for us more than anyone.

In an interview on Tagata Pasifika’s Talanoa, speaking about An Indigenous Ocean, Salesa said this book was different from other more policy-facing work, like Island Time. He also noted that he was happy his academic essays are now in a more accessible format through publication of An Indigenous Ocean and available to more people and that is significant. Like many scholarly works, these essays were predominantly first published in academic journals requiring a subscription and usually a university affiliation, so although still couched in academic convention, the book makes them more available than they were. But it piqued my attention to hear Salesa acknowledge the difference between audiences of his policy facing work for a ‘wider audience’ and his less accessible scholarly essays in An Indigenous Ocean. It seems like it's time to collapse the wide and narrow audiences into one.

Pacific history deserves to be widely read and understood, by Pasifika people and the general public. Salesa is a fierce critic of the lack of incorporation of Pacific history into world histories and critiques these exclusions in his book in essays like The World From Oceania and others. The General Non-Fiction Ockham award will undoubtedly have brought attention to his book and hopefully Pacific history, and yet it's hard to ignore that these essays were written with other academics in mind and that will always be a narrow audience. Shifting the narrative of Pacific history also means changing the conventions of academic discourse and expanding its reach as well as impact. Decolonising the academy includes decolonising how academics communicate in writing. At this stage of relative security in his career and from a position of influence, he has an opportunity, if he chooses, to shift the discourse and further decolonise academic writing by intentionally writing to connect with a more expansive audience in his future work.

Siniva Bennett’s family are from Vaiusu, Upolu and Fatumafuti, Tutuila. She has a Master’s from the University of Hawaii and a law degree from the University of Oregon.