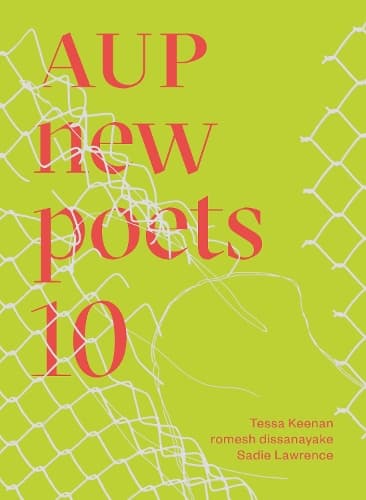

Review — AUP New Poets 10

Reviewed by Hebe Kearney

AUP New Poets 10 is bright and fresh. It feels very of-the-moment, and its scope extends in many directions, from Taranaki to Sri Lanka to teenagehood. It is composed of three chapbooks by three dazzling poets. Each poetic voice is distinct, yet each grapples with the confusion of becoming, as well as the beauty of belonging. This unites them, and causes moments of harmony for the reader.

Tessa Keenan’s poems play out against the backdrops of Taranaki and Wellington, and are made resonant by deep connections to her whenua and tupuna. This is seen no clearer than in ‘Mātou’, when her father ‘pointed at the grass, turned back to us / and yelled / “this is your tupuna!”’ (p. 5). Her poems sometimes come in a rush and sometimes freeze a single moment to examine it. ‘A Room Recording’ is the former – it is breathless, and forces you to take in all the details of the scene as if you had just entered it.

There is no punctuation except for a lone full stop at the end of the piece, giving a last-chapter-of-Ulysses-eque cadence. ‘Coastal Driveway Song’ similarly captures a single moment in a rush, only using dashes to punctuate the piece. Keenan returns often to the idea that the present is multiple – filled with precious detail. Summoned to witness these moments is a ‘we’ that might just be everyone Keenan has ever loved. There is a sense of plurality to the perspective in her poems as they capture moments, and adorn them in verse. Keenan’s poetry takes ‘that space asks for something to enter it.’ (p. 6) and fills it, cleverly using all the gravitas that comes with belonging.

romesh dissanayake’s poetry is also grounded in the present, but more in a vernacular sense. At times its nowness brings whimsy – playing with trendiness to produce tongue-and-cheek pieces which still have heart. ‘Six a.m. in Colombo / Cinnamon Gardens’ manages to seamlessly contain both the word ‘skuxx’ (p. 37) and the line ‘i’m no good at keeping people alive / after they’ve gone / especially when they / passed in service of me’ (p. 36).

This contrast makes these moments hit harder. His poetry also transports readers directly into its world by capturing unique detail. ‘Favourite Flavour House’ presents a catalogue of employees in various positions, evoking a bustling kitchen, and making the reader feel comradery with ‘Indika holding / a courgette between her legs’ or Duncan swiping ‘leftover food… with the side of his palm into a hole in the bench’ (p. 42).

Interestingly, this piece does something similar to Keenan’s piece ‘Scurvy Girls’, listing an array of characters engaged in odd, specific, and intriguing activities. Readers will enjoy comparing these two pieces, and witness their differing intrigue.

Sadie Lawrence’s chapbook was written between the ages of seventeen and nineteen, and unpicks this journey viscerally. An autism diagnostic report gets maggoty, and ‘a butcher wanders his gristly Eden’ (p. 57) while ‘girlhood is made of blood’ (p. 60). There is a freshness to Lawrence’s writing, but also a current of wisdom with startling revelations: ‘I can see ghosts / and I can see people / but I could never tell the difference’ (p. 76). She does interesting things with language, such as turning ‘barefoot’ into the verb in the line ‘we barefoot the grass’ (p. 55). At times, this is playful, and at others it adds to the weight of a piece. Ultimately, what she conveys are growing pains, and meaningful reflections on the journey. This cannot be underestimated, because ‘This is not growing up. / There must be an alien thing / deep in the chasm of me / that I am growing around’ (p. 62).

Overall, this collection is a gripping read – three distinct chapbooks full of captivating and blistering detail about the now. It is a treat to hear such distinct voices speak in these chapbooks, and to feel your brain tugging at the threads of them, looking for similarity and contrast.. Similarity is found in the way each poet’s chapbook is grounded in their experiences. Anne Kennedy’s debut as AUP New Poets’ editor has produced a shiny, astutely assembled collection. Kennedy also summed up its nature perfectly in her editorial, commenting that ‘each poet writes, in different ways, a compelling present’ (p. vii). Rejoice in the multiplicity of presents – read this book!

Reviewed by Hebe Kearney