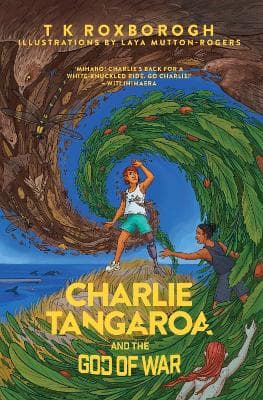

Review: Charlie Tangaroa and the God of War

Reviewed by Barbara Uini

Set in the East Coast town of Tolaga Bay, Charlie Tangaroa and the God of War is the second installment in the Charlie Tangaroa fantasy adventure series by author T.K. Roxborogh. From the very first page the story captivates the imagination, presenting a setting that is intrinsically Aotearoa, weaving in aspects of te ao Māori, and featuring characters for whom tikanga Māori is an integral part of everyday life. It brims with fast-paced action and mystery, shady villains, ambiguous strangers, feisty kids, one sadly messed up kid, and a bunch of passionately misguided conspiracy theorists. Thrown into this mix are fierce atua and ancient rivalries, patupaiarehe (forest fairies), sacred stones and secret guardians, and at the heart of it all, Charlie Tangaroa, a protagonist who young readers will undoubtedly root for, and quite possibly wish to have as a best mate.

If you haven’t read the first book in the series, Charlie Tangaroa and the Creature from the Sea, don’t worry—there’s plenty of backstory sprinkled throughout to bring you up to speed on the key elements of Charlie’s world; aspects such as his unique mixed heritage as a child of both the physical and spiritual realms, his special connection to the sea, and the important role his koro plays as confidante and mentor.

Fourteen-year-old Charlie and his younger brother Robbie are leading ordinary, everyday lives—fishing off the wharf, helping out in their mother’s shop, and, in Charlie's case, worrying about the potential changes ahead if Robbie is sent away to school in Tāmaki Makaurau. But trouble is brewing and comes to a head when a visiting scientist is attacked, a distressed stranger turns up in their mother’s shop, and a mysterious man begins poking around town. The town is thrown into chaos as protestors and conspiracy theorists descend. Charlie, with his unique gifts and heritage, finds himself in the midst of the action - caught up in ‘atua-level negotiations, dodging black SUVs with tinted windows and an epic swim to stop the baddies.’

Classic adventure story stuff, but Charlie Tangaroa and the God of War also has deeper messages to convey. Just like onions and parfait, this book has layers. Whānau and sibling relationships, friendship and loyalty, tolerance and respect, land ownership and kaitiakitanga, standing up for what is right - these themes permeate the story, enriching the narrative without feeling heavy-handed. Children are encouraged to protest against the protestors - to have a voice. A browse of Roxborogh’s blog reveals these themes reflect personal values that inform her practice, both as a teacher and an author. Roxborogh speaks about the importance of ‘shining light on the human condition … to challenge the reader to reconsider their own view of themselves and, hopefully, modify the way they think and act.’ Understanding, she asserts, is the antidote to fear and discrimination.

Charlie’s mother echoes this ethos of tolerance, telling Charlie, ‘I don’t think it’s helpful to think of the protesters as evil. Misguided - sure. Wrong - absolutely. All I ask Charlie, is that you keep an open mind. Keep questioning everything you hear people say. Think about what might motivate someone to act. It will make you a better person.’ And it’s not only the adult characters who display such wisdom. Charlie’s classmate Molly shares a similar view, saying ‘I don’t think they’re bad people. They’re just selfish - they think their way is the only way to effect change.’

We live in a world where our tamariki are too often confronted with division and prejudice—where perspectives are polarized, framed as black or white, good or bad, different or the same. It is refreshing then to read a book such as Charlie Tangaroa and the God of War—a book that encourages reflection and grace over judgment and rejection. While this might sound heavy and earnest, Roxborogh weaves in these underlying issues with a light touch, ensuring they don’t overshadow the story, which is an imaginative, page-turning adventure from start to finish.

Barbara Uini is a teacher, writer and artist. She has a BA in English, History and Māori Studies and a PGDip in Learning and Teaching from Massey University, and a Masters in Creative Writing from the University of Auckland.