Review: Edith Collier: Early New Zealand Modernist

Reviewed by Linda Herrick

This is a good year for artist Edith Collier, daughter of Whanganui, the city which belittled her vibrant, modernist work when it was first shown at the Sarjeant Gallery a century ago.

Collier had recently returned home after nearly 10 years of art education in London, with an exciting new direction inspired by exhibitions from Europe and tutors like expat New Zealand artist Frances Hodgkins. Back in Whanganui, Collier was invited to contribute works to a group show at the Sarjeant. Whanganui, and indeed, New Zealand, was not ready for modernism. Already diffident by nature, Collier’s confidence was bruised by the local paper’s sneering dismissal. She rarely exhibited again, and her enthusiasm for painting started to waver.

Instead, she cheerfully immersed herself in family life as the eldest of nine children, with a growing roll-call at one stage of 37 nieces and nephews. She cared for them and they, in turn, loved her and nurtured her artistic legacy.

That legacy is finally fully emerging. In November, the refurbished Te Whare o Rehua Sarjeant Gallery in Whanganui’s Queen’s Park will re-open after a decade of restoration work marrying its imposing classic architecture with a modern new wing. The wing will house the Sarjeant Collection, including more than 400 works on permanent loan from the Edith Collier Trust, a longstanding partnership between the family and gallery.

An Edith Collier exhibition will run as part of the gallery’s grand re-entry into the world, called Nō Konei/From Here.

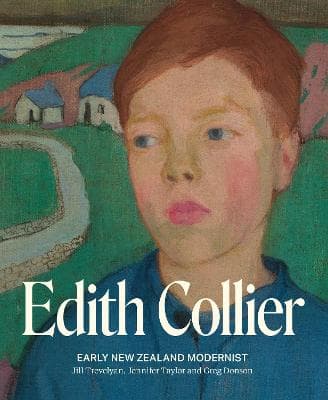

As a prelude to those celebrations, Massey University Press’ gorgeous new book on Collier is a comprehensive introduction to her life and art which follows on from Joanne Drayton’s excellent biography published in 1999.

It includes an impressive range of perceptive essays (and a poem), more than 150 immaculately reproduced art works (her glowing greens are a revelation), and striking photos of Edith during her passage through life.

Editor Jill Trevelyan’s opening chapter offers a thorough overview of Collier’s life from 1885-1964. Although Collier’s views of herself were modest - “I am not a gusher”; “A peculiarity I am and always will be” – others disagreed.

When Collier attended Frances Hodgkins’ painting school in Cornwall in 1920, Hodgkins, not given to gushing herself, noted: “I’ll make something of her.” But she already was something.

At the time, Collier was 35, single (she never married) and had spent eight years studying art in London, with the financial support of her parents in Whanganui.

Before Hodgkins appeared on the scene, distinguished Australian artist Margaret McPherson (later Preston) was also an important figure in Collier’s style evolution, joining her on painting trips to Bonmahon, a tiny fishing village in County Waterford, Ireland. Collier’s studies of faces, figures and buildings from her two Irish sojourns – included in the book - are revered in Bonmahon to this day.

With work shown at the Society of Women Artists in London in 1917 and 1919, Collier’s future was looking bright. But her parents, affected by the post-war economic crash, called her back home. She arrived back in Whanganui in January 1922, with crates filled with 350 art works, including some nudes, which her father burnt.

Trevelyan’s empathetic account traverses the following years, during which time Collier painted intermittently until her death in 1962, at the age of 79.

At this point, the guest contributors take over, focusing specifically on particular works and periods of her life. The essays include “Women on the move”, by art historian Catherine Speck, on Collier’s work documenting London during the war years, notably her landmark oil painting Ministry of Labour – Recruting Office, 1917-18; and “A benign deluge”, by poet-writer Greg O’Brien, who examines a group of exquisite works, including the book’s cover image, Boy Against Landscape, 1917-18.

Essays by curators Julia Waite and Milly Mitchell-Anyon appraise Collier’s “outlier” works The Lady of Kent, and her distinct trio of elongated nudes, Frivolity, Folly and Figures at Pool, stripped of traditional Rubenesque curves.

The quality of writers heaping praise upon Collier in the book is remarkable, including (of course) Joanne Drayton, Jennifer Taylor, Gretchen Albrecht, Priscilla Pitts, Lizzie Bisley, poet Arini Beautrais and her nephew Gordon Collier, whose short piece is called “Aunt Edith”.

Gordon Collier writes lovingly about Aunty Edie’s visits, armed with painting materials, and a family outing to Tangiwai where she started work on an oil landscape of Ruapehu (dated 1939-40), which will take pride of place in the Sarjeant’s new wing.

One of the book’s great rewards towards the end includes the section on Collier’s visit to Kaawhia in the late 1920s, where she painted landscapes and portraits of kuia Tiro Tiro Ponui and Ritihia Kaora, whose whakapapa is detailed by their descendants. Their moving words link to a fascinating record of a series of hui in 2023 at Maketu Marae in Kaawhia connecting those paintings from the Sarjeant with Ngaati Mahuta trustees for the first time.

What a momentous impact Collier’s work is having. As Jennifer Taylor points out in one of the final essays, the establishment of her legacy is “unique to New Zealand” because of the forethought of her family, who initiated the relationship with the Sarjeant nearly 70 years ago to keep her works safe within the gallery’s care.

As Jill Trevelyan writes in the “Adventure in Art” section, “Edith Collier’s career has often been seen as one of wasted talent. There are so many ‘what ifs’ in her story.” But she adds that Edith’s return to Whanganui brought rewards she may never have received had she stayed on in England to take on the formidable challenges of becoming a professional artist. “In Whanganui, there was real compensation in being loved and needed.”

Her niece Helen Gordon adds: “She should have been more selfish, but she had such a loving heart – she put other people first.”

The Sarjeant’s opening in November, and this very beautiful book, mark our opportunity to join the party putting Collier first. She deserves it.

Linda Herrick is an Auckland-based freelance arts and books reviewer and feature writer.