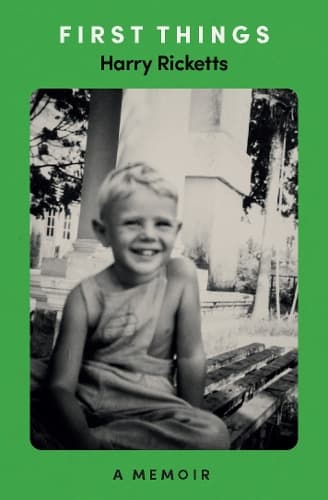

Review — First Things, by Harry Ricketts

Reviewed by Andrew Paul Wood

It’s a difficult thing appraising a memoir. What do you measure it by? The quality of the writing? How interesting the life is? The latter seems too presumptuous but it does have an impact on the reader’s experience of the latter.

When a brilliant polymath like Harry Ricketts takes to memoir, you just know it is going to be something special. First Things does what it says on the tin. It’s an exercise in autobiography defined by firsts: the first things that he can remember, the first times he experienced certain things – his first poem, his first shotgun, the first time he went hitchhiking, the first time he ever saw his father angry.

Consequently, this is the early part of Ricketts’ life, the Hong Kong and Oxford years, with stints at a prep school in Kent and Wellington College in Berkshire. Perhaps we may assume a future volume dealing with his arrival in Aotearoa. Ricketts was born in London in 1950. An army brat, his father was a British career officer who had served in the Second World War and thence to British possessions in Asia; Malaya and Hong Kong in the 1950s.

It is always interesting to see how an accomplished literary biographer like Ricketts, author of the acclaimed The Unforgiving Minute: A Life of Rudyard Kipling (1999) and Strange Meetings: The Lives of the Poets of the Great War (2010), tackles his own life story.

One thing that stands out as shocking and alien is the class consciousness that Ricketts grew up in, such as young Harry being informed by his mother that he couldn’t go to his friend’s birthday party because his friend’s Irish father was of a lower rank in the military than his father, though this may in fact have had more to his mother’s insecurities about her own Truro background (pp. 16-17). This leads into a rather delightful parody of Philip Larkin’s ‘This Be the Verse’, soundly putting the poet in his place about blaming one’s parents for one’s own shortcomings.

Reluctantly I have to say I found the school years a bit of a slog. That’s nothing to do with the quality of the writing (which is excellent) or the subject (Ricketts is intrinsically fascinating), it’s just that from where I am in geography and time it’s very hard for me (or many New Zealanders, I suspect) to relate to English public school culture. But also, paradoxically, it’s almost too familiar from so many other books (biography and fiction), and other media. And that’s on me. A couple of half-hearted schoolboy homoerotic dalliances or ‘rubbing up’ aside, Alms for Oblivion it isn’t, and reading it through that kind of literary trope lens feels unavoidable.

The Trinity College years were far more engaging for me, though still in that liminal space between almost too foreign, and almost not foreign enough. It’s sometimes said that Cambridge is a university and Oxford a finishing school. To some extent this appears true of Ricketts’ experience. Though by the 1970s it was a lot less Brideshead and a lot more Velvet Underground with a cast of dodgy characters. Ricketts is brutally honest about his triumphs and caddish moments. Some of this period gives a sense of the emerging intellect and cultural sensibility, but the part that riveted me were the years lecturing in Hong Kong, largely because it provided the spark of otherness that enlivens the rest of the book and gives some of the flavour of an empire in decline.

It is a bit of a shame that some of the best stories in First Things are other people’s, such as the Hong Kong colleague who had been a student of Edmund Blunt, recalling how the poet wept when teaching the First World War poets because they had been his contemporaries, and the expat, who, when his English girlfriend found the fake eyelash of his Chinese mistress in the bathroom, in a panic declared it ‘a fairy’s merkin’. Of particular interest was Ricketts’ recollections of the difficulties of teaching Hamlet to Chinese students navigating the cultural differences between Western and Chinese understandings of ghosts and filial piety. If anything, I could have happily read an entire book on that one topic.

Please do not take any of my minor subjective cavils as particularly significant criticisms. There are few, if any, of those to be made. Even parts I found a little dull still served up their portion of delight, surprise, insight, erudition and humour.

Reviewed by Andrew Paul Wood