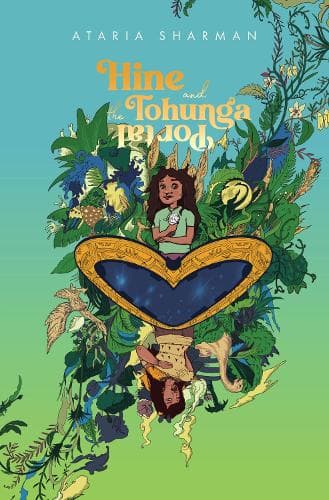

Review: Hine and the Tohunga Portal

Reviewed by Dan Rabarts

A day that starts out like any other turns into a journey to another world and a desperate quest to save our own, in Ataria Sharman’s Hine and the Tohunga Portal.

Our two young heroes, Hine and her little brother Hōhepa, are walking home from school, squabbling like siblings do, when they find themselves snatched away to an alternate world of taniwha and dark magic. Having raised an army of enslaved animals and beasts, the evil tohunga Kae has now kidnapped Hōhepa with even more nefarious plans in mind. Hine has to save him but she has her own problems to overcome in this strange and dangerous world.

Sharman takes us to a land part history and part myth, a parallel space where Māoritanga is a power all its own, such as magic bound up in the sound of a waiata or the motions of a haka, and where the birds and beasts and atua of Aotearoa roam as battling armies. Hine and Hōhepa are joined in their struggle against Kae by a host of animal allies including a moa, a rat and a dog, armies of patupaiarehe, giant eagles and capricious warrior kea, and the fire-goddess Mahuika, who never misses an opportunity to remind everyone of how that scamp Māui stole her fingernails.

Some of these characters are cheeky and sly, or cute and cuddly, but in spite of this, the story maintains an increasingly dark edge with Kae’s wicked intentions constantly returning to overshadow the warm edges of the narrative. By turns endearing and brutal, The Tohunga Portal has all the elements readers would expect of a mythic apocalyptic middle grade novel.

As the story winds itself towards its climax, we learn of the importance of whakapapa, both as a source of power for our villain and also as the means by which our heroes will find the strength they need to defeat this enemy. A complex metaphor emerges, not only of the importance of knowing our history, of our roots as the foundation of whānau and self, but of the dangers of losing our knowledge of those roots or, worse, having that knowledge turned against us.

Hine and Hōhepa, for their young years, present us with the challenges faced by many urban Māori, in that even though they attend a te Reo immersion kura, they don’t know much about their ancestors. This gap in their knowledge comes at a heavy cost; Sharman uses this deficit to explore just how much is lost when we don’t hold onto our past and share it with our children.

By the same token, the importance of whānau in the wider sense, those from outside our families who support us and help us through our struggles as if they were family, in the figures of Hine-te-iwaiwa and Tinirau, comes through as a powerful reminder that unity is the most powerful weapon we can wield against adversity, but more importantly of how crucial it is that we teach this to our children. Because we can’t always know what they might be struggling with that we can’t see and they need all the empowerment they can muster to meet the challenges the world will throw at them.

Taniwha (supernatural being/monster that lives in the water), waiata (songs), haka (ceremonial war dance), atua (gods), whānau (family), patupaiarehe (fairy folk, fair-skinned mythical people who live in the bush on mountains), whakapapa (genealogical lineage), kura (school).

Reviewed by Dan Rabarts