Review: Home Base: poems on life as a regular force cadet 1964–1966

Reviewed by David Hill

Readers over that certain age may remember how confident of the nation's safety they felt during the mid-1960s. So they should have: I was doing my Compulsory Military Training.

I spent 14 weeks in Waiouru Military Camp. I learned to fire a 7.62mm semi-automatic rifle, a Bren Gun, a Sterling sub-machinegun; I learned to walk around the edge of the parade ground, never across it. Otherwise, the RSM might scream at you and the RSM's scream could melt tungsten. I learned that “You disgusting rabble!” as roared at us by NCOs was very nearly a term of affection.

And I learned never to compare myself to the Regular Force cadets training at Waiouru. They were learning to be real soldiers. We were – well, a disgusting rabble. They were also young men (I don't recall a single woman) with their own experiences and narratives.

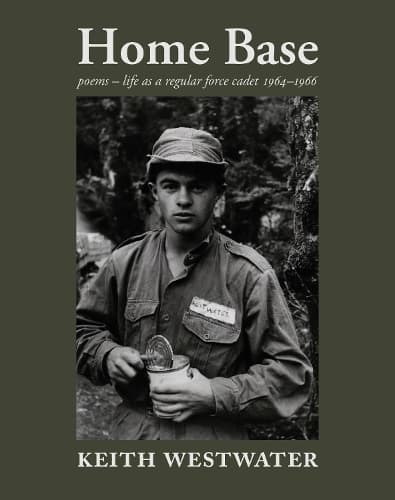

Keith Westwater was one of them and he's assembled this engaging narrative to outline his military life. Aged 15, his semi-functional household gave him an ultimatum: “join.... Regular Force Cadet School or leave home”. So, he became a member of the species he describes as “(g)iven to mass group-choreographed displays of marching.....youthful appearance, short hair.”

The Lower Hutt author has already published a memoir of his testing 1950s boyhood and you can see Home Base as a sequel to the earlier No One Home. It's an inventive fusion of some 80 pieces: verse, the Army's unique style of correspondence (“You will....You will be...You will....”), visual images, diary entries, vocab lists, menus, 1964 Top Ten list, historical footnotes from his three years as a cadet.

We get the apprehensive talk – “I hear they're pretty strict” – on a troop train taking 140 teenagers towards the Volcanic Plateau. Then there's barracks and kit, “Brasso, Bayleaf and Blanco,” food and fatigues, NCOs and officers, “Peter Snell v Taihape.”

Westwater and others “do the marchie marchie,” are spoken to by Charles Upham, shouted at by ex-All Black Tiny Hill. There's leave, during which a girl smiles at him outside the movies in Taihape. There's always Ruapehu, in its “freezing worker's white bonnet / and tussock apron.”

He did well, was selected for officer training, became CSM of his company. He formed part of an honour guard for Lyndon Johnson; felt sure Mr President sniggered at “such a short-arse.” A confrontational poem about US aggression accompanies the memory. Graduation parade / dinner / ball are followed by an affecting tribute to a fellow cadet killed just three years later in Vietnam.

He made friends. He also saw others fail; the frequently jaunty anecdotes are counterpointed by darker details – one cadet slits his wrists; four others die in a stolen Land Rover; a predatory teacher exploits the vulnerable.

And he grew up, acknowledging the sense of worth the Army gave him, learning “standards by which I have lived the rest of my life.”

The writing is accessible, uncluttered. He's a tidy poet: lines fit cleanly together; structure is firm; images restrained and relevant. A few bits walk rather than march, and you'll probably prefer those where the boy speaks directly, rather than those where the man looks back at said boy.

You'll like the wryness and parodies and enjoy the trade secrets – how to bring boots to a high gloss by setting fire to the polish. (Bandages sometimes resulted.) You may remember the times of winklepickers, Brylcreem and Old Spice. “It wasn't such a bad place,” the author concludes and you should also recognise the quintessential male New Zild voice of that phrase. I probably saw Keith Westwater marching around Waiouru Military Camp. I'm gratified to have read his account of those times. It brought back a lot, always authentically.

Reviewed by David Hill