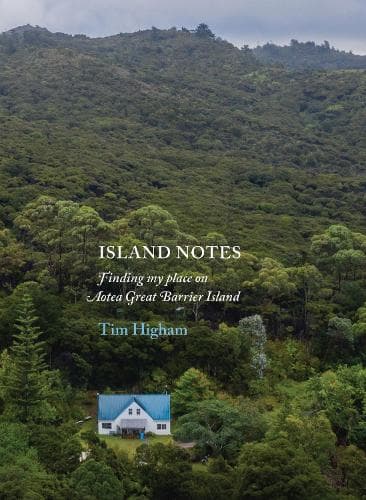

Review: Island Notes: Finding my place on Aotea Great Barrier Island

Reviewed by Sarah Ell

Great Barrier Island/Aotea lurks on the edge of Auckland’s consciousness, only its highest peaks sticking their heads up over the horizon. Despite its proximity to New Zealand’s largest city, the Barrier remains literally ‘off the grid’ — all electricity has to be generated by diesel or solar — so it’s the ideal bolthole for alternative lifestylers and those wanting to live close to nature.

Among them is nature writer Tim Higham, who has collected a series of vignettes on life on the island in this slim but intimate volume, part memoir and part meditation on island life. Higham, a journalist who has written widely for scientific and environmental media, here turns the focus on himself and his nearly two decades of experience of living full- and part-time on Aotea. It’s a loosely chronological narrative which also turns in unexpected directions and folds back on itself, dipping into scenes and moments, giving the sense of flipping through a box of photographs.

The text is highly discursive — ideas are picked up and put down, sometimes returned to and sometimes not — and sometimes frustratingly light on detail; we never really find out why the Highams came to the island, how they funded this lifestyle or the reasons they came and went.

As the title suggests, at times it felt like Higham’s notes for a longer book and I longed for him to go deeper, dwell a little longer, make a movie rather than providing a snapshot. His wealth of experiences both on the island and elsewhere — working and seeking enlightenment in Southeast Asia, supporting artists in Antarctica, his childhood in the United Kingdom — could fill a much longer book and maybe one day they will.

Higham is inspired and informed by a canon of other writers, from Roger Deakin and Gavin Maxwell, Bill McKibben and Rick Bass, to Norwegian auto-fiction specialist Karl Ove Knausgård. The book is not composed to tell a linear story or provide the whys and wherefores, as you might expect from traditional memoir. Instead, it captures a sense of being ‘out of time’ amid the wandering thoughts of the writer, like being privy to a personal stream of consciousness.

As might be expected, Higham’s writing on the natural world and his interactions with it (especially when surfing) are luminous: gannets diving into a workup of fish are “a feathered hailstorm, an unexpected pulse in the movement of the sea;” Aotea’s “defining aroma . . . the accumulation of honey-dewed leaves and seed-capsules of mānuka and kānuka holding sway over the airwaves.”

One of his most obvious stylistic quirks is the single-sentence paragraph which initially makes for slightly uncomfortable reading. Groups of sentences and phrases which are (or could be) linked are left to dangle alone, so at times the text reads like an extended prose poem of individual statements rather than flowing smoothly.

However, once I put aside my logical, rational ‘city’ thinking cap, as it were, and moved onto ‘island time,’ the reward was simply in bathing in the language and the emotions, inhabiting the descriptive passages which bring Higham’s experiences and memories to life.

Perhaps Higham puts it best himself; in this case, when contemplating an enforced ‘lay-up’ following an operation:

“Sometimes you are better to let go, to be released, briefly, from the job of keeping up defences.

The island invites the same response.

What are you doing with all that running around in the world?”

Reviewed by Sarah Ell