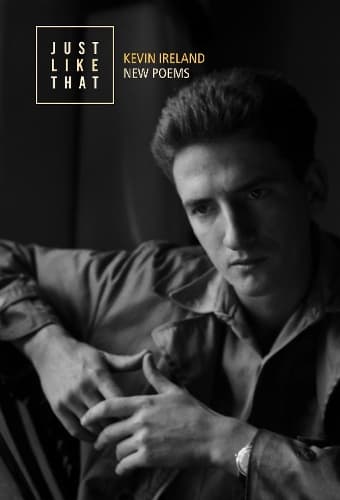

Review: Just Like That - Kevin Ireland New Poems

Reviewed by Graham Reid

One of the many advantages of the literary life is that it can continue into what we charitably call “advanced years.” When many retire from employment they are obliged to find things to fill their waking hours: petanque, U3A, gardening, even more golf, a book club . . .

Writers are their own book club. And for those once again taking their thoughts to the keyboard, the accumulation of years means more memories and ideas to explore while continuing that sedentary but intellectually stimulating life.

The late Gordon McLauchlan wrote his final, enjoyable Stop the Clock: A Memoir On Aging with Dignity, Grace and Humour – full of his customary twists of phrase, smart observations and quotes from a walk-on cast of fellow writers and thinkers – when he was in his late 80s and knew the game was almost over.

And at 88 with 26 poetry collections, two wonderful memoirs, a novel, short stories and essays behind him, Kevin Ireland still writes with clarity of thought, insight and a mischievious twinkle in his eye. One of those many writers McLauchlan quotes is the French philosopher Michel Montaigne: “Take care that old age does not wrinkle your spirit even more than your face”. Ireland is the living embodiment of that precept, although inevitably in his new poetry collection Just Like That, he addresses ageing.

In The Mind and Body Problem Solved, his superannuated body, which exists as a separate entity, insists it is too sore to go out. But he forces it and “amazing how my parts and pieces were restored/Not an ache or twinge – or virus – bothered me./ I can't recall when last I checked my various bits/and felt them ticking over even half so happily.”

Elsewhere he writes of lunching with “old friends” and how once the talk was of pranks and passions but now it is of the attrition of years: “Yet we turn this/into jokes as we try to keep a grip - /though the ones that get the laughs/seem to end with slapstick punchlines/where we fall flat on our faces.”

In considering our precarious planet, he notes “it has to face a legion/of crazy saboteurs who would love to blow us all to bits” but the many problems must take second place to “the intricate, exhausting task of pulling on my socks.”

That kind of sly wit and observation is everywhere in this collection: “It adds a risky feeling to the morning/when you check your latest slide towards collapse./ You've been attacked again at night by demolition experts/with a flair for comic artistry. They've worked you over/ in your sleep…”

Above my desk I have a yellowed cartoon of a man with his head in hands and a long-suffering woman looks on as he says, “You know the trouble with writing, it's just work.” And it is. But in the hands of the best, like Ireland, it is a ceaseless and never-finished pleasure which is conveyed to the reader.

Ireland, of course, writes of poetry itself with economic lines which hum with insight: “Love poems sometimes blossom/from dishevelled gardens in the head”; “Good poems will greet you in the morning/with a crafty smile as they encourage you/to wear clean socks . . .”; and “ … poems feed off disorder/and need human mess.”

As this collection illustrates, “Poems can concern themselves about anything they like./They're not obliged to be about momentous issues . . .” In The Best We Can Do, a poem about poets and poems - (“it's not the kind of task that pays the rent . . . my modest profits have mostly/vanished into books and casual cases/of good wine”) – he celebrates losing the thread of what he is writing about.

And in Writer at Work he concludes, “But the double factor keeping him at work/is that he has a room all to himself/and untold years to spare.”

“Incongruity lies at the heart of poetry” he says in Problems With Images.

He is bemused by change, the chores of children in his youth were delivering papers and mowing lawns, “Both tasks now are occupations for grown-ups.” He writes about the romance of trams, of friends now gone and how time could be suspended over long boozy lunches at Auckland's Mai Thai restaurant, now closed.

He also delights in the magic of moments, as when he was a child and his father showed him the first five pound note he had ever held, “a real bloody fiver”. But then “they began to pop from pockets everywhere/and they became mere money.” A man bangs a roll of them on a table and the magic evaporates, “they looked quite like a peeling/old, infected, paper sausage.”

This entertaining and thought-provoking collection however opens with 10 Poems for Pandemics and even here, in a topic he knows must be thread-bare for its ubiquitousness, Ireland finds insight. Initially this pandemic “had the decency to aim itself/at those who live in distant lands/and bought their food at market stalls.” But then, “the underlying horror of it all/remains the nonstop bluster/and the unrepentant lies, the evasions/accusations, plus the smug refusal/to accept even the basic duties of high office/revealed by all the ambitious braggarts/and the pompous farts who went/to so much trouble to gain/a show-off moment in the spotlight/of their times.”

However, he finds humour in that now he can walk on the deserted golf course without worrying about being hit in the head by an errant ball. He even, despite the knowledge that “plagues existed in the air,/ propelled by breezes, spooky smells or even casual glances” offers there may be hope.

“Yet perhaps this visitation will unite us and one day even/seem a useful force for good… though it does come hard that millions suffer, old friends die/and some still snuffle for obstructive answers/in feeble nonsense and ludicrous conspiracies.”

Above my desk I have a yellowed cartoon of a man with his head in hands and a long-suffering woman looks on as he says, “You know the trouble with writing, it's just work.” And it is. But in the hands of the best, like Ireland, it is a ceaseless and never-finished pleasure which is conveyed to the reader.

To précis Kevin Ireland's themes or selectively quote from his poems, as done here, is to diminish them: they are complete beings with independent but interconnected lives of their own. They deserve to read and enjoyed – just like that – in their entirety.

Reviewed by Graham Reid