Review: Kate Edger: The life and times of a pioneering feminist

Reviewed by Atakohu Middleton

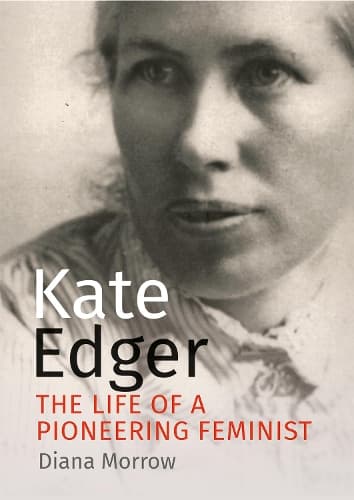

When I started my postgraduate study some years back, I was very grateful to receive several grants from the Kate Edger Educational Charitable Trust, whose main purpose is to help women further their education. I became intrigued by Kate, who in 1877, aged 20, became Aotearoa’s first university graduate with a Bachelor of Arts.

But there wasn’t a vast amount about her that was easily accessible, apart from a few online biographies. So when this book was published, I pounced on it and found that there was far more to Kate than championing women’s education – she also worked for women’s suffrage with the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, the protection of women and children from violence, prison reform, courts for young people, women’s right to work and equal pay, legislative change in various areas and, after World War I, international diplomacy.

It seems that we have Kate’s reverend father, Samuel, and her mother, Louisa, to thank for creating an environment that allowed their four daughters (they also had a brother) to flourish in an era when women were regarded as the intellectual inferiors of men. Samuel and Louisa came from long lines of religious nonconformists, emigrating from England to Aotearoa in 1862 when Kate was one.

They sought a more just society based on Christian values where individuals could realise their potential and put no barriers in the way of their daughters’ education. After her BA, Kate founded and taught at Christchurch Girls’ High school, becoming the country’s first university-educated teacher. She earned a masters degree in mathematics while there, then founded Nelson College for Girls. She married a Welsh preacher, William Evans, who shared her Christian socialist values and they embarked on various social reform projects as well as producing three sons.

Although Kate fits neatly into what we now call “first-wave feminism”, she did not see herself as strongly feminist in outlook – rather, she believed in creating a society whose members were mutually supportive and compassionate, and believed that these values were inculcated in the home. Kate was clear that the most important work a woman could do was raise a family and protect family wellbeing – and the education of future mothers was a critical part of that.

In a 1923 article called The first girl graduates, Kate asked rhetorically whether the higher education of women had justified itself. Her response was oblique: “It is too soon yet for a complete answer to be given to this question, but thousands of university women are proving by their lives that it has not unfitted them for home-making, the noblest sphere of women’s work.”

This sort of quote is, of course, the public Kate speaking. We get a good sense of Kate’s public persona from the many media articles about her in the colonial press, which often reported speeches she made or reports she had written. She presents as calm under pressure, serious, persistent and possessing a strong sense of fairness. However, very little of the private Kate apparently remains, leaving little insight into her private thoughts; this is a gap the author acknowledges.

Another gap in the book – and this may also be because of the lack of relevant personal documents – is how far Kate’s support for equality of opportunity for women, children and families extended to Māori and the nature of her engagement with tangata whenua. There is little mention of Māori involvement in Kate’s work, apart from the fact that the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, of which Kate was president at one stage, had many Māori supporters. It may well be that she lived in a Pākehā bubble, like many settlers of the time.

However, the book is, overall, a well-written and engaging read. Like the best biographies, it paints a vivid picture of the social, cultural, economic and political backdrop to its subject’s life. Kate may have been gone since 1935, but she remains an inspiration.

Reviewed by Dr Atakohu Middleton