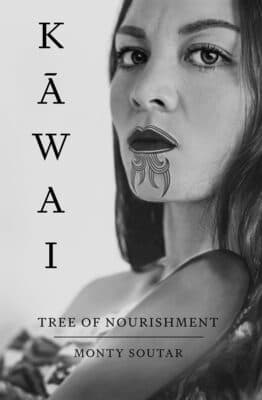

Review: Kāwai - Tree of Nourishment

Reviewed by Vaughan Rapatahana

He pukapuka tino pai, he pukapuka hira. Kātuarehe he whakaahuatanga o te kupu tuku iho pono o tēnei whenua. Tēnā koe a Monty. A very good book; an important volume. An outstanding depiction of the true history of this land. Thank you Monty.

Kāwai Tree of Nourishment uses this format – an italicised passage of te reo Māori with an English language translation – regularly, centering Māori language in the story. Similarly, Soutar used it copiously in the first of his series, Kāwai For Such a Time As This. It’s a great reflection of the continued growth of te reo Māori, despite the best efforts of a slim cabal of right wing politicians to stymie revitalisation and growth.

He pukapuka tino pai, he pukapuka rongonui. He aha ai? Why? Because it’s easy-to-read, absorbing, and generally easy to follow. The reader learns a great deal about the pre-1840 history of this skinny country, particularly from the points of view of ngā iwi Māori. We are increasingly aware that the early meetings between ngā iwi Māori and the visiting Pake-pakehā, the latter in their increasingly populous guises, were inimical to Māori, especially in the rohe in which Kāwai is set – the East Coast of the North Island. The arrival of the musket led to Northern iwi decimating East Coast iwi. The arrival of Pake-pakehā mariners and whalers led to terrible diseases and afflictions – not all physical – in local Māori populations. The steady beat of missionaries further divided Māori communities, as many turned to Christ at the expense of tohunga Māori – traditional cures and curses were subjugated, almost eliminated, rather like Māori themselves pre-1840 and into the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The publishers’ insert that accompanies the book quotes Soutar as saying, ‘Many New Zealanders do not fully comprehend the overwhelming initial effects of colonisation on Māori, particularly the significant population decline by 1840’. This is a mighty effort to educate while also to entertain through a historical novel. His quintessential theme is expressed through an aphorism lurking later in the book:

Kei tua i te awe kāpara, he tangata kē, māna e noho te ao nei, he mā (Beyond the tattooed face, strangers will occupy the land, and they will be white).

Yet, Soutar does not himself proclaim iniquity and inequity, does not preach injustice; does not manifestly incite anger and angst. His is an historian’s steady and steely eye depicting what really happened in the nascent nation’s earlier years. At the same time, his romantic picture of several amours and whānau interactions, graphic delineations of Māori warfare tactics and tasks, and rendering of everyday realia o te ao Māori, leave us with a cleverly multifaceted novel, a resource book for all who want to learn more authentically about the early years of Pākehā arrival in and around the shores of their country. Kāwai The Tree of Nourishment is a balanced and evocative bilingual compote of Mills and Boon Māori, Ranginui Walker, and Mauri, the movie. Indeed, I imagine that we will eventually flock to the inevitable film versions of Soutar’s monumental chronicle.

Kāwai The Tree of Nourishment revolves around the life and exigencies of Hine-aute, the grandaughter of the key protagonist of the earlier novel, Kaitanga. Hine is – until later in the book at least – the fulcrum through which everything is seen and around which the prolific activity revolves, including her relationship with her two sons, Ipumare and Uha. She is witness and provocateur, mirror and catalyst, although her role noticeably diminishes as the book progresses. This is similar to the first book, where it is almost as if Soutar needs to complete his tuhituhinga more frenetically, in this case probably because the complex parade of ngā Pake-pakehā arriving, mingling, influencing, and whitewashing te ao Māori entails more and more activity, far greater upheaval and radical transmutation. Solid characterisation and simple plotlines can become submerged or overwhelmed in this process.

The book remains grounded in the near present. Two of Kaitanga and Hine’s descendants – Te Koroua and The Young Man – introduce, interpolate, and conclude each volume with their own kōrero. Where Te Koroua, born in 1903, is the mentor, The Young Man, born in 1961 like Soutar, is the eager mentee who maintains tēnei hinonga rongonui (this important project) and indeed does so with these two fine books. Each chapter commences with he whakataukī, while there is also a rather comprehensive glossary, a helpful regional map, and the multi-paged adumbration of The People of Kāwai too: Soutar is a tidy author.

I predict that this time around Kāwai will win at the Ockhams. It is essential reading for those in our increasingly multicultural nation. Soutar’s description of the serious obstacles and the ‘arduous journey’ he underwent when completing the book is testament to his prowess in managing to koha us all the finished version.

Coda.

Some of my own experiences validate some of the historical nuances Soutar details in this book, showing just how much research he has done, and how accurate and true Kāwai Tree of Nourishment is, notwithstanding some arbitrary character interactions.

Whetū-matarau is mentioned in the book, and a second wave of Ngāti Pūhia invaders who accosted Ngāti Porou in and around Kawakawa-mai-tawhiti. I can attest that even today locals in Matakaoa have vivid tales to tell about these events as maintained throughout iwi and hapu lore. Visiting Ngapuhi are still sometimes scolded because of the invasion by their musket-bearing forefathers. For years my home was directly under Whetū-matarau, where the survivors fled, and became besieged. An ongoing offspring of the so-called musket wars, eh.

When Hine’s son Ipumare relinquishes his training and insights as tohunga and takes on the mantle of Christianity, he admits to losing his ability to instill traditional medicines and to install death inciting curses and mākutu. The Young Man may ask his kaumātua, ‘So, what happened to our tohunga?’, and the older man will reply, ‘Aue, i tae mai te Pākehā’ ‘Why, the Pākehā arrived, of course’, but I want to state we never did fully relinquish our taha Māori, even given deliberate historical attempts to suppress essential components of it. We have never lost our distinctive tohungatanga, which is palpably flourishing. For example, everyday I partake of ngā inu rongoā Māori and recently have been undergoing ngā maimoatanga tikanga (traditional treatments) mō taku wairua.

My point? That Soutar’s necessary books present to readers the lived world of ngā iwi Māori as from our eyes and our minds i mua, i muri, ināianei. While the author depicts devastation caused by the arrival of Europeans, his pukapuka also serve to show that ngā iwi Māori are ngā mōrehu (survivors). These volumes are vital because they portray this dichotomy so vividly and viscerally, and will continue to do so.

Ko ēhea pukapuka e kōrero ana ahau nei? Ēnei pukapuka! Which books am I talking about? These books!

Ngā pukapuka tino pai, ngā pukapuka hira.

Reviewed by Vaughan Rapatahana (Te Ātiawa)