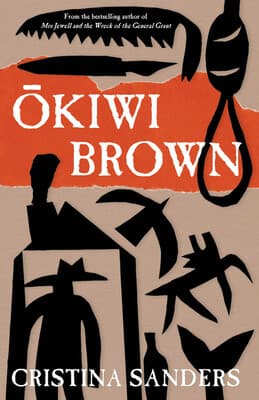

Review: Ōkiwi Brown, by Cristina Sanders

Reviewed by Sarah Ell

Hawke’s Bay writer and reviewer Cristina Sanders first came to wider attention when her 2022 novel Mrs Jewell and the Wreck of the General Grant was shortlisted for the Acorn Prize at the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards. She has remained in historical territory for her new novel, Ōkiwi Brown, but returned to the setting of her first book, Jerningham: early colonial Wellington, in all its rough and grubby glory.

The book gets off to a cracking start, with a suspected murderer — Scottish body-snatcher William Hare — escaping the death penalty in Edinburgh and being set loose to wander who knows where. In this imagining, we are asked the question: why not Wellington? Throughout the book, flashbacks to Hare’s series of heinous crimes, enacted with his partner William Burke, are told reportage-style, hinting at what kind of man might be living among the hard-working, unsuspecting settlers of Port Nicholson.

Ōkiwi Brown draws heavily on historical fact and real-life characters to paint a picture of lives lived on the colonial fringe, away from what passed for ‘respectable’ society in the 1840s and ’50s. Two historically recorded suspicious deaths — first a child’s body found in a stream, his head cleaved open,in 1846, and a drowned drunk washed up in 1852 — frame Sanders’s narrative, which is populated by whalers, soldiers, itinerants, drinkers and fighters — mostly male but some unlucky females occupying an even lower social standing. Historical events such as the war in the Hutt Valley in 1846 occur slightly off stage, leaving the cast struggling with the day-to-day reality of making a living and surviving on what can be a harsh and dangerous frontier.

We never see events from the point of view of the titular character, ‘hotel’ keeper Ōkiwi Brown, who may or may not be Hare; what we learn of him comes only through the eyes of those who encounter him at his rough-and ready accommodation and boozing house in the eastern bays of Te Whanganui a Tara. They include the widowed William Leckie, in thrall to the bottle, struggling to keep his head above water and take care of his young daughter, Mary; colonial soldiers Patrick Spolan and James Meney, brought to New Zealand to fight a war then set loose in its wilderness; and Ōkiwi’s reluctant wife Nan, a Māori woman captured by whalers at Rēkohu Chatham Islands and left to fend for herself. None of these characters has a particularly happy, stable or secure existence, and Sanders has resisted the urge to give any of them a traditional character arc: no one is redeemed or transformed by their experiences. People suffer. People fight. People die. Bit like real life.

Sanders is a master of description, and her word-paintings of early Wellington are infused with both familiarity and an obvious love for the place. A newly built ship on a slipway ‘appeared like the sun-bleached bones of a whale, its curved ribs pale in the morning light, the tide draining from its belly.’ Ships in the harbour drying their sails on a windless day float ‘irregularly rigged and magically still on the pale blue wash.’ Cleverly, we see things as the characters would see them: the girl, Mary, touches a horse’s face ‘and it felt like wet cake. It had huge holes in its nose where the warm air came out.’

Characters, too, are given vivid treatment: one is ‘a big man with a shaggy face full of hair and the swollen nose of someone who took his drinking seriously’. Another has ‘nothing specifically about him to indicate malevolence, his face neither crooked nor dark, though his accent, from the uglier parts of Ireland, indicated he was not fully to be trusted.’ The introduction of Meney, a homesick Irishman who has a side-hustle sketching dirty pictures for his fellow soldiers and officers, is a particular tour de force. You can sense that Sanders had fun writing him:

'Someone’s boots were near his nose, mud mountains that smelled like trees and soil and stagnant water. It wasn’t like the mud from home. Irish mud came in all different odours — horse shit was a constant, and the sludge that came out the back of the brewery, ripe with hops and yeast. The first was his childhood, the second his youth. But this muck had no condiments added. No fish heads or animal blood, no buckets of slops thrown from a window mixed into the syrup. It had an odour of unadulterated brown.'

It’s not all mud and violence, though: Sanders uses humour, often blackly, to good effect. There’s a running gag about exactly what kind of alcohol the men are drinking; side characters such as a small brown-and-black dog with an unusual name. The relationship between Meney and Spolan in particular provides comic relief, Meney’s distinctive point of view leavening the text and lightening what could otherwise be quite dark. And the book finishes with a fantastic last line which is as unexpected as it is laugh-out-loud funny.

In Ōkiwi Brown, Sanders does what every good historical novelist should: fills in the interstices of the official record with vivid but credible imaginings of what may or may not have happened. As the character Meney observes of the legend of Ōkiwi himself: ‘It was just a story, of course, of half-remembered facts stitched together, but there was the bones of truth behind it. Like every good story: it could have been true.’

Sarah Ell is an author and editor of fiction and non fiction titles for children and adults, primarily on NZ history and natural history, and is based in Auckland. She has a Masters of Creative Writing (First Class Honours) from the University of Auckland.