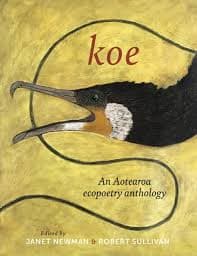

Review: Koe: An Aotearoa ecopoetry anthology

Reviewed by Elizabeth Heritage

Reviewing anthologies makes me think about the importance of the editors’ introductory writing to establish the kaupapa. In Out Here: An anthology of Takatāpui and LGBTQIA+ writers from Aotearoa (2021), the editors said that “It’s not our intention to present a canon or a tidy history or to make a definitive statement”, which I’ve always thought was a bit of a cop-out. There’s no such pussy-footing about with Koe: An Aotearoa ecopoetry anthology edited by Janet Newman and Robert Sullivan (Ngāpuhi, Kāi Tahu). Sullivan’s foreword starts with a dictionary:

Koe refers to the cry of a bird. H.W. Williams’ Dictionary of the Māori Language also defines ‘koe’ as a scream; a disturbing scream from the forest, or the shore, or the marshes, or the bush-lined gullies and gorges, or its absence from the paddocks, the eroded dead timber hillsides and mountains, the oxidation ponds and outfalls.

Newman’s introduction is brisk. “‘Can poetry save the earth?’ … Of course, the answer is no.” Well okay then! Earth-saving is off the table. So what are we here for? “Koe … charts the genesis, development and heritage of this country’s ecopoetry from an undefinable point in Māori settlement until today.” Right. Off we go.

Koe is divided into three sections: 17 poems from the period up to the nineteenth century, presented roughly chronologically; 43 from the twentieth century sorted by author surname; and then 60 from the present (also presented alphabetically), each with an introduction by Newman. Her prose style is still in recovery from the effects of her PhD (on local ecopoetry), so be prepared for sentences such as “A postcolonial ecocritical framework contends that literature that has been sidelined by settler hegemony reveals comprehensions of nature and the human relationship with it that differ from prevailing narratives.” But given the general ungraspableness of poetry I found her confident laying down of the law reassuring.

Koe has a good mix of work by tangata whenua, tangata tiriti and tau iwi, with many poems presented in their original te reo accompanied by translation into English. Poems by former Poets Laureate, such as Elizabeth Smither, David Eggleton and Selina Tusitala Marsh, sit alongside works by lesser known writers, with contributions from 114 poets all up. The first poem Koe presents us with is the well-known whakatauki

Hutia te rito o te pū harakeke

Kei whea te kōmako e kō?

Here translated by Patricia Grace (Ngāti Toa, Ngāti Raukawa, Te Āti Awa) and Kerehi Waiariki Grace (Ngāti Porou, Te Whānau a Apanui) as:

If you destroy the flax plant

From where will the bellbird sing?

With its air of warning and neat encapsulation of the threat of climate change, this whakatauki sets the stage beautifully. The poems that follow are concerned, as you would expect, with environmental degradation, colonial violence, and the consequent loss of mana.

Newman writes that she’s noticed the word ‘keening’ recurring. This must have planted some seed in my mind because the two words I started noticing were, oddly enough, ‘glory’ and ‘alien’.

Let us start with glory. ‘The Passing of the Forest’ from 1898 is William Pember Reeves’ second entry in Koe. (In the poem on the facing page he had rhymed ‘queer’ with ‘pioneer’, which, as a queer reader, made me chuckle.) The opening line is the strong declarative sentence: “All glory cannot vanish from the hills.” Glory reappears several decades later in ‘Te Rapa, Te Tuhi, me Te Uira (or Playing with Fire)’ by Keri Hulme (Ngāi Tahu, Kāi Te Ruahikihiki). She addresses the “hoons of the Pacific” doing nuclear testing: “There is no glory in what you do”. I really like the idea of glory as something that is possessed naturally by hills and is unattainable by environmental destroyers.

And now on to alien, here used to mean settlers. I am Pākehā and tangata tiriti, and so my relationship with the whenua of Aotearoa is … I can feel Newman wanting me to say ‘problematic’, but I’m sick of that word so instead I’ll just say ‘weird’. I don’t like thinking of myself as an alien but I kind of am: my parents literally came here from the other side of the world. In ‘The Land and the People (III)’ Charles Brasch describes “the newcomer heart, / Needing slow-paced generations” as “half alien.”

Later, in ‘The Land without Teeth’, Rebecca Hawkes takes it one step further and describes her white self as “that / impregnable alien / pricklebitch skeleton … me & my entire invasive species”. Yikes! But the poem I found most alienating was Fleur Adcock’s ‘Last Song’. In writing against nuclear testing she veers into profound ableism:

goodbye to sweet certitudes of our

mammalian order, where to be

born with one eye or three thumbs

points to not being human.

I know she’s trying to make a point about chemical poisoning but come on – people with disabilities and physical differences have always been with us and are a perfectly normal part of humanity.

Before ending this review, I must mihi to the book’s designer. The pages are wider than normal, and this spaciousness makes for a much gentler reading experience than the subject matter might suggest. I can do no better than to finish with ‘Papa-tu-a-Nuku (Earth Mother)’ by the legendary Hone Tuwhare (Ngāpuhi, Te Uri o Hau), which I reproduce here in full:

We are stroking, caressing the spine

of the land.

We are massaging the ricked

back of the land

With our sore but ever-loving feet.

Hell, she loves it!

Squirming, the land wriggles

in delight.

We love her.