Review — Max, by Avi Duckor-Jones

Reviewed by Clare Travaglia

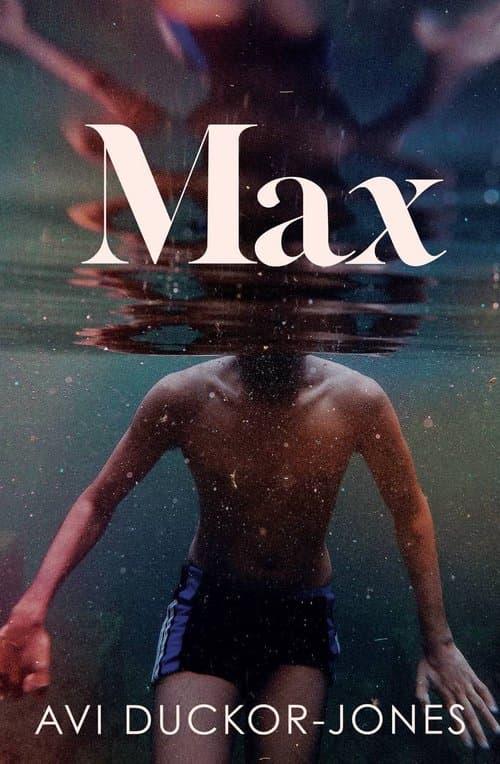

Avi Duckor-Jones’ tender coming-of-age novel Max is the story of a young man’s search for the missing spheres of his identity, and for acceptance of the pieces he already holds.

Duckor-Jones, son of celebrated New Zealand author Lloyd Jones, is also well-known for being the first winner of reality show Survivor NZ. His other previous endeavours include teaching, writing for Lonely Planet, BBC Travel, and the NZ Listener, and winning the 2018 Viva la Novella prize for his first novel, Swim.

Max opens with its titular character navigating his last few days of high school. But along with more typical teenage identity struggles, Max was adopted, and is also trying to understand his own sexuality. Dial-up internet, chat rooms, and Radiohead and Moby on CD place the story somewhere around the turn of the millennium, where Max says of the homophobia that surrounds him, ‘These things stick. They accumulate into a warning, a singular message of rejection of which I’ve had enough of already. So I stay silent.’ (p50).

Max stays silent and hidden, noting that he must ‘mask the part of myself that people are scared of.’(p46). On the outside, he appears robust and resilient. His feet are ‘hardened to the point where I can walk across rocks like this, sharp and peppered with small barnacles and periwinkles’ (p5-6). But on the inside, he is lost and uncertain. Max’s parents are ‘straight, domestic, stable’ (p.50), and Max is burdened by the immense expectation that he should fit this mould.

Max’s roguish best friend Fletch is one of the most vivid characters in the book: charismatic, talented, effortlessly cool. Max is in awe of Fletch, describing him as ‘better than us, who all play by the rules. He is himself’ (p11). It is this simple truth that Max has been unable to attain, but all that he longs for. Duckor-Jones portrays the surreal feeling of leaving school with all its nostalgia, excitement, eeriness, and anticipation. When out surfing, one of Max’s greatest freedoms, he describes ‘a closing, a beginning. Spray blinds me. I lean into it, cry out, pumping to keep up the momentum, letting it all go and then staying, if only for a moment, in the comfortable space of gliding between two worlds’ (p7). The writing is thick with metaphor, with Max himself caught between two worlds and finishing school threatens to rip apart the seam he has been so carefully treading.

Max and Fletch make it through their end-of-year exams, but on the night of their leaving party, everything that has been building within Max boils over. The events that unfold result in severed relationships and a period of isolation and depression. Max throws everything away—from his university plans to his belongings: his books, clothes, his basketball and wetsuit. ‘Then I begin to sleep more than I leave. And then the moving stops. I just stop’(p99).

Eventually something draws Max out of bed, out of the house, and out of the country, where he embarks on a search for belonging, identity, acceptance, love. Max seeks answers that he desperately hopes will ‘fix’ him, solidify him. At the barber, he imagines that the problems in his past ‘have been shorn off, and now lie in scattered strands on the barbershop floor, ready to be swept away’ (p143).

On a micro-level, setting is beautifully evoked through the book. ‘The sky shifts from navy to powdery blue, a thin seam of pale orange running along the roofs of small white cottages’(p3). It is a distinctly, immersively New Zealand book, but locations go mostly unnamed. The reader only has vague references to ‘up north’ (p57) and ‘down to Wellington’ (p20) to get their bearings.

Max tests the strength of relationships. Those that can withstand the weight of truth, the brittleness of others under pressure. It balances confinement with soaring moments of freedom and is both heart-wrenching and hopeful.

Reviewed by Clare Travaglia