Review: My First Real Pash and Other Stories

Reviewed by Erica Stretton

My First Real Pash and Other Stories examines life’s transformative moments, exploring how they happen and how they reverberate through the future. Each of these 12 stories peers at interpersonal conflict and how societal pressure affects it, using a New Zealand setting to deftly illustrate the cultural context.

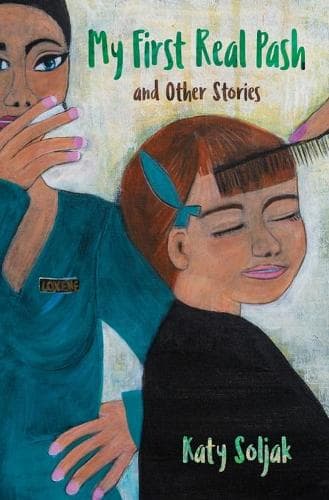

Katy Soljak is an artist, writer and musician living on Waiheke Island; each story is preceded by an artwork illustrating a scene from the story to come and the stories are set in the spaces she’s inhabited. One of her storytelling strengths is in imagery: cultural references and concrete details put us vividly into her world. In the titular story the main character’s sister is dressed, “in her big pink Rock N’ Roll skirt with the blow up inner tube petticoat and polka dot poodles,” and they dance to the Troggs’ Wild Thing and Peggy Sue in a tiny church hall.

The collection begins with teenage life, with the characters feeling the effects of peer pressure and social inequality. Then it shifts to darker themes: relationship betrayal, extramarital affairs, abuse. In Troy, the narrator watches jealously as party girl Troy flirts with her husband. Rather than lay down concrete action and feelings as in the other stories, Troy leaves the reader with a sense of unease. Soljak uses a lighter touch and underlying subtext to elevate the story, making it the highlight of the collection.

The author often makes her characters unlikeable, labelling them as lookers, braggards, Bollywood taxi drivers, hipster dyke and sheilas amongst others, instead of imbuing them with more considered depth. Two stories might need a content warning: in Queensbury Rules at the Baron’s Lunch, a group of obnoxious folk watch a fight that ensues after one man takes offence at being asked for his recipe for scallops and announces he’s “not a farkin’ homo.” Nobody intervenes, instead they watch: “it was sexy, primal even.” It’s a difficult, painful read, as is the last story in the collection, which delves into sexual assault on a child by a family member, with the protagonist alone and unable to escape.

Men often behave badly in these pieces, or without regard for others, and the stories explore the resulting fallout on women’s lives. Sometimes, as in File This, the female protagonist takes revenge: Brenda has been summoned by her ex, who has been dumped, and thinks Brenda might like to give it a go again. When Brenda flips, her rage takes her out of control. Other times, it’s the women who let down their sisters: the woman who dismisses an artist attempting to sell her cards in a bookstore; the mother and hairdresser who butcher a teenager’s hair and ignore her distress; the cool girls whose conditional approval cause one to drop her first boyfriend, and the injured sister who bullies and derides her caregiver sister. There’s a feeling that it’s pointless to speak up against these injustices, that unlike Brenda, you can’t win.

There are moments of hope. In Tripping in Melbourne with Mum and the Indian Prince, the last paragraph deals with kindness and how it exists in the world. The final sentence of the story says, “in this world of chaos and war, there are still honourable, decent people...”

Other stories echo this idea of kindness but the impact would be more powerful if Soljak had taken opportunities to deepen character and language. It is a missed opportunity that harmful stereotypes within the stories are not subverted or challenged to provide deeper critique of society.

The back cover blurb declares that “these stories condense the experience of a whole life into a few pages,” and the collection has a definite feel of a world observed, memories collected into fiction to illustrate life’s turning points, damage that can be inflicted in a short time but then continue to echo through a person’s life for many years thereafter.

Reviewed by Erica Stretton