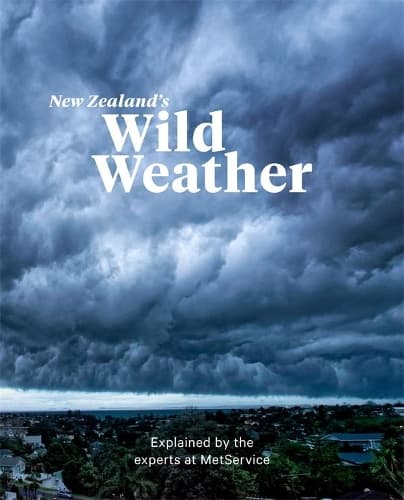

Review: New Zealand’s Wild Weather

Reviewed by Alison Ballance

I began reading New Zealand’s Wild Weather after experiencing a classic bout of wild Wellington weather. I was flying in from Dunedin and our flight was due to land at the same time an intense southerly front crossed the capital. The pilot attempted to land twice and each time had to accelerate away at the last second as wind shear made a landing attempt too dangerous.

We retreated to Christchurch to refuel and wait for conditions to settle and eventually, three hours late, we bumped and shook our way back through the turbulent air and, to everyone’s relief, made safe contact with the runway.

After that experience, the first chapter I jumped to in the book was the one on wind, to see what it had to say. “Looking at wind records (2011–20) from 15 airports in our main centres, it is not surprising that Wellington Airport recorded the strongest gust, at 146 km/h. In addition, the number of days in a year on average that Wellington gets gusts of 90 km/h or more is 22, with the next-highest number of days being 14 at Invercargill, then seven at New Plymouth.”

I’m actually a little surprised that Wellington only gets 22 days of gusts above 90 km/h as it feels like many more than that, and I wouldn’t have picked Invercargill and New Plymouth as the silver and bronze winners in the wind gust Olympics. I’ve already shared these watercooler stats with several friends and there is no shortage of similarly shareable weather facts in the book.

“Most rain in New Zealand is actually melted snow that has grown rapidly above the freezing level.” Who knew.

“[In] 1948, Tauranga recorded a whopping 34 millimetres of rain in just 10 minutes.” Blimey.

“New Zealand’s most notorious katabatic is the ‘Greymouth Barber’, so called because it is reputed to be cold enough to give you a very short haircut! Reaching speeds of up to 30–40 km/h, it is like a river of cold air pouring out of the Grey Valley on the West Coast.” Note to self – this river of cold air is only a few hundred metres wide so should be easy to escape if I find myself in it.

And there are how many kinds of frost? Read on to find the answer.

New Zealand’s Wild Weather has been produced by the New Zealand Metservice, with a helping hand from long-time environmental writer Gerard Hutching. It is part meteorology textbook, part Guiness Book of New Zealand weather records, and part glossy self-promotion of a national weather service doing its best to provide accurate forecasts in a country beset by fickle, changeable weather. Four seasons in one day and all that. It also includes first-hand accounts of people experiencing extreme wild weather.

Most chapters begin by bursting our preconceived weather balloon, by reminding us that although New Zealand can be very wet, windy and dry, it is not the wettest, the windiest or the driest place in the world. Still, we can take comfort that there aren’t many countries that can claim the 18-plus metres of rain that falls each year in the Cropp River catchment on the West Coast.

And while Central Otago is no Atacama Desert, Wild Weather tells us that “in 1964, Alexandra recorded the least rainfall in a year: 212 millimetres. In February–April 1939, the tiny community of Wai-iti, Marlborough, just inland from Lake Grassmere, experienced the longest stretch without rain officially recorded: 71 days.” Makes me feel thirsty just thinking about it.

Given our national fascination with weather, I’m sure New Zealand’s Wild Weather will sell well (as did Erick Brenstrum’s The New Zealand Weather Book two decades ago) and will feature under many Christmas trees as presents for those hard-to-buy-for folk.

That said, the book is, at times, a slightly clunky read and suffers, as much as benefits, from having been written by a committee of experts (at least 24 people contributed in some way or another). A very laudable attempt to put climate change front and centre by making it the first chapter doesn’t, to my mind, quite succeed as it keeps referring to processes and events that appear in later chapters.

To avoid climate change being relegated as an afterthought at the end of the book, I think instead it might have slotted nicely in the middle. By then the reader will have developed a grounding in the fundamentals of why our weather is the way it is and would then appreciate more how global warming will contribute to greater extremes in future.

New Zealand’s Wild Weather is too ‘text-booky’ to entice most us to read it cover to cover in one sitting, but it merits frequent short visits. You never know what you might find. How about a new kind of cloud, apparently quite common in New Zealand but only added to the International Cloud Atlas in 2017 – asperitas clouds, from the Latin meaning ‘roughness.’

And the book has entries for five kinds of frost: white frost, hoar frost, window or fern frost, rime frost and black ice. Brrr.

Reviewed by Alison Ballance