Review: Ngā Tai Whakarongorua/Encounters

Reviewed by primoz2500

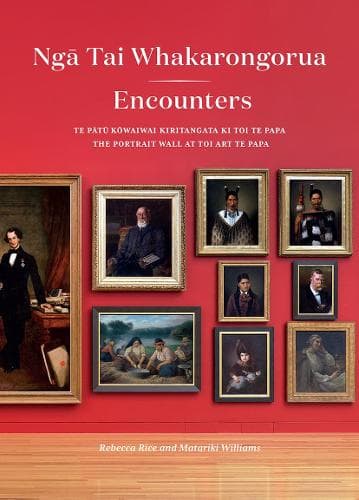

This modestly sized (112 pages) but well produced book is a detailed guide to Te pātū kōwaiwai kiritangataki Toi Te Papa/ The Portrait Wall at Toi Art Te Papa. Comprising 36 items, all but a couple being painted portraits, the display is said to be the most popular art exhibition for museum visitors at Te Papa Tongarewa Museum of New Zealand.

Closely hung in an elliptical cluster somewhat waka-like in appearance (I presume this is deliberate), the portraits range in date from about 1770 (John S. Copley’s 1771 portrait of Mrs Humphrey Devereaux) to about 1910 (a portrait by Charles F. Goldie of Rotorua carver Ānaha Te Rāhui). In other words, the portraits belong to Aotearoa New Zealand’s colonial period.

They are a deliberately miscellaneous and heterogeneous group of pictures. In Rebecca Rice’s words: “Portraits of Pacific, Māori and European share the same space. Some are public and formal: others feel like intimate glimpses into private worlds. Renowned rangatira sit alongside unknown subjects. There are artists, makers, doctors, captains, husbands and wives, widows, mothers, girls and boys. The artists, too, range from the (relatively) celebrated: John Webber, John S. Copley, George Dawe, Gottfried Lindauer, James Nairn, Petrus Van der Velden, Charles Goldie, for example, to the obscure and anonymous. With a single exception – Margaret S. Carpenter, who provides an 1826 portrait of the Victorian novelist Wilkie Collins’ grandmother (no obvious connection to this country) – all are men, though women are prominent among the subjects of the portraits.”

The format of the book is straightforward and designed to be useful to those either viewing the exhibition in person or reading about it at home. After a double introduction by the authors in both English and Te Reo Māori, a brief essay by each author, one in English and one in Māori, then accompanies each picture. These are not identical in the sense that one is a translation of the other but are separate essays in the two languages; Te Papa Tongarewa is obviously an institution which takes biculturalism and bilingualism seriously.

A typical entry consists of a double-page spread, with text on the left giving the essential information about the artist and the work, and a good quality photographic reproduction in colour on the right.

A somewhat unusual and worthwhile feature is that in about a quarter of the pictures an additional two-page spread is given to further information usually including a photograph of the back of the picture or an ultraviolet or infrared photo of the portrait with notes pointing out interesting features of provenance, signature, framing, revision or conservation.

In one instance – a 1904 portrait by German artist Wilhelm Dittmer of Whanganui chief Take Take Rangitupu – an unrelated sketch of a Māori boy appears on the back. In the case of Copley’s 1771 portrait, an ultraviolet image of the picture shows the presence of different varnishes and various stages of conservation work in process. The back of John Webber’s 1785 portrait of Poedua, daughter of a chief in the Society Islands, sketched on Cook’s third voyage and completed in London, shows an inscription in the artist’s hand and various devices for strengthening the frame of the large canvas.

Such reminders of the materiality and historicity of the paintings as objects adds another dimension to the psychological, aesthetic and historical connotations of the portraits themselves and the intriguing conversations between them created by their juxtaposition both in the museum itself and in this worthwhile publication.

Reviewed by Peter Simpson