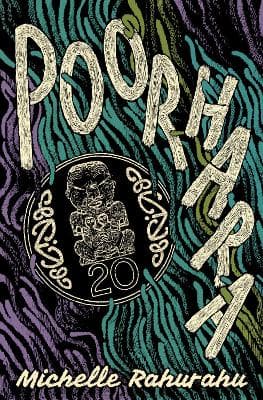

Review: Poorhara, by Michelle Rahurahu

Reviewed by Savannah Patterson

Poorhara, the debut novel by Michelle Rahurahu (Ngāti Rahurahu, Ngāti Tahu – Ngāti Whaoa), is a powerful and haunting exploration of family, cultural identity, and the scars left by intergenerational trauma. It speaks to those who consider themselves ‘cockroaches’ of Aotearoa—those who have grown up in poverty, in environments of neglect, fighting for survival and resilience. This poignant novel reflects the experiences of the true poorhara of the world.

The novel follows cousins Erin and Star as they road-trip across the North Island in a 1994 Daihatsu Mira, seeking to reconnect with their whenua, which ‘was a fabricated memory’ to Erin. As they travel, Rahurahu invites readers to explore not just the physical landscapes of Aotearoa but also the emotional and cultural terrains of the characters. The backdrop of small, unnamed rural towns emphasises the universality of Erin and Star’s experiences, places that are familiar yet starkly neglected.

Symbolism is used powerfully to deepen the reader’s understanding of the characters’ struggles. The cockroach is a recurring symbol, representing survival and resilience in the face of adversity: “Her whaanau had survived two decades in the house by being low maintenance: they scuttled like cockroaches, didn’t complain, didn’t make themselves known if it could be helped. If the ceiling burst, the landlord might think of selling the land under them.” Cockroaches endure even the harshest conditions. So do Erin and Star.

Erin is burdened with the responsibility of caring for the moko while still trying to process her grief over a loved one. She entertains the cousins and assists her aunty with her cleaning job. Erin is an observer of the world, especially those more fortunate, and she fantasises about a life of privilege: “She saw lots of cafes down the main street, and all of them had the same groups of young white people in them…They all looked the same… She could be a girl with straight hair who drank milky coffees in cafes…What name would she have? What about Jessica? Jessica was a pretty name.” Trapped in her current reality, her observations and fantasies reveal a deep sense of disconnection, a longing for a life different from her own.

Star returns home after three years at university, struggling with separation from his culture, family, and identity as a takatāpui. Tormented by his past, he experiences both mental and physical deterioration, and relies on self-medication to numb his pain. His escalating toothache becomes a symbol of his unresolved emotional struggles. Despite his attempts to ignore it, the persistent ache, described as “foul, sour, vomit-bitter,” mirrors his inner turmoil.

Despite the tragic elements woven throughout the narrative, Rahurahu skillfully infuses relatable humour into the characters’ interactions, providing levity amidst the heavy themes. Their banter and witty observations about their circumstances serve as a reminder that humour can coexist with hardship, making their journey both heartbreaking and real.

Poetic allegory plays a crucial role in illustrating generational trauma. The tale of the dark sister and the children of the fern serves as a metaphor for the burdens carried by Māori communities, reflecting how past traumas shape the present. This allegory is prominent throughout the novel, with the dark sister symbolising unresolved historical pain and the lasting impacts of colonisation. The children of the fern reflect the younger generation, such as Erin and Star, who struggle to thrive while bearing the weight of their ancestors' suffering.

Rahurahu’s narrative style is distinctive, using em-dashes to denote dialogue, which blurs the boundaries between thought and speech. This emphasises the emotional distance between the characters, adding layers to their communication struggles. The integration of text messages and fragmented memories brings a contemporary feel, allowing glimpses into the characters' past and the barriers in their communication. Furthermore, the inclusion of New Zealand’s three official languages—Te Reo Māori, English, and New Zealand Sign Language—enriches the narrative, reflecting the diverse linguistic landscape of Aotearoa. Rahurahu’s personal experience of being raised by tāngata turi adds authenticity and depth to the portrayal of communication nuances.

Rahurahu aptly captures the intersection of cultural identity and personal struggle. This is also reflected in her previous works, such as the short story The Garden published by RNZ, and her personal reflection The Rebellious History of New Zealand Sign Language, published by The Pantograph Punch. Poorhara won The Modern Letters Fiction Prize and was shortlisted for the Michael Gifkins Prize, which cements her as an important emerging voice in New Zealand literature.

Poorhara is unflinching and deeply affecting, yet essential for its portrayal of cultural identity, intergenerational trauma, and the resilience required to keep fighting. Fans of Coco Solid's How to Loiter in a Turf War will appreciate Rahurahu’s depiction of modern Māori experiences, complex characters, and the richness of Aotearoa’s cultural landscape. For those interested in contemporary New Zealand literature exploring the depths of identity, family, and survival, Poorhara is a genre-bending must-read.

Savannah Patterson (Ngāti Porou) holds a Master’s in Creative Writing from AUT. A former journalist, she now teaches English in Waikato and has been published in takahē.